Long Take: An obituary for Mint.com, which inspired a fintech revolution

$145B Intuit promotes Credit Karma as its more commercial PFM

Gm Fintech Architects —

Today we are diving into the following topics:

Summary: Intuit's decision to shut down Mint.com marks the end of an era for one of the original pioneers in personal financial management (PFM) software. Mint's intuitive platform revolutionized how users interacted with their finances, offering a seamless experience that aggregated personal banking and investment information. Despite its innovative start, Mint's growth stagnated over the years, leading Intuit to transition users to Credit Karma, a platform with a stronger emphasis on financial product offerings. As Mint.com sunsets, we reflect on its significant contribution to making financial oversight accessible and user-friendly, as well as bootstrapping the embedded finance movement.

Topics: personal financial management, venture capital, blockchain

If you got value from this article, let us know your thoughts! And to recommend new topics and companies for coverage, leave a note below.

Long Take

Friends Like These

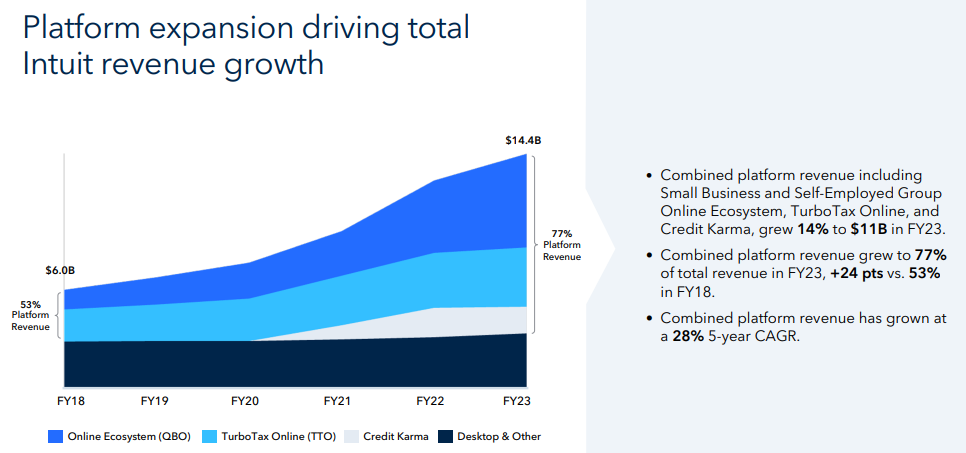

Intuit is a $145 billion market capitalization company, generating about $14 billion in revenue. Its history is anchored in tax preparation and accounting software for consumers and small businesses. While it has a leading position in that sector, the story of the company is particularly impressive when it comes to navigating the rise of online finance, and their famous acquisition of Mint.com.

Intuit has done an absolutely incredible job of adding digital finance to its desktop software business. The legacy business is large, but destined to stay flat or shrink given Internet trends. Meanwhile, in the last 5 years alone, Intuit revenues have grown from $6B to $14B — inorganically in small part — pointing to smark navigation of the digital finance waters. Since they bought Mint, Intuit has added a staggering $137B of enterprise value.

Here’s to death and taxes!

Pointing the Way with Mint.com

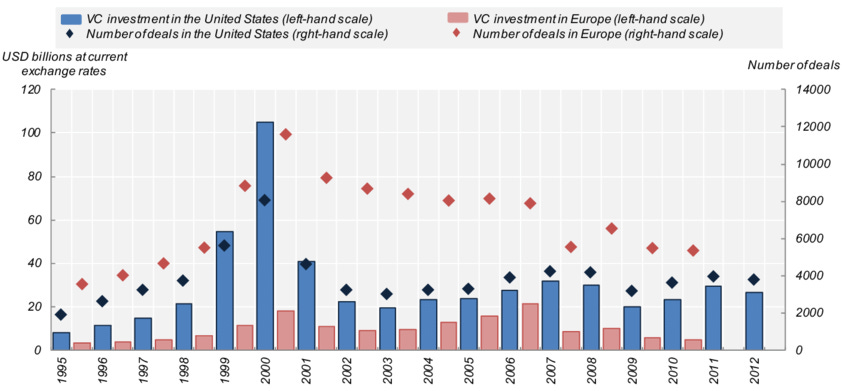

When we rewind back to the mid-2000s, remember that there was a deep hangover from the bursting of the 2001 Internet bubble. George W. Bush was President, and engaged the United States in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Interest rates were pushed down by the Federal Reserve to stimulate the economy, and cheap money was flowing into housing, and thereafter into derivatives structured on top of housing.

Houses, however, are not the Internet.

Venture investing fell off the roof and didn’t recover until much later.

If you were to ask about “fintech” venture capital, the answer would be that the sector hadn’t even been established yet.

But, in the background, Facebook and Google were moving interactive software into the browser and seeing meaningful commercial uptake. Web 2.0 emerged as the answer to a static Web 1.0, promising connectivity, interactivity, and a modern customer-centric experience. As you know, many banks are still trying to get there today.

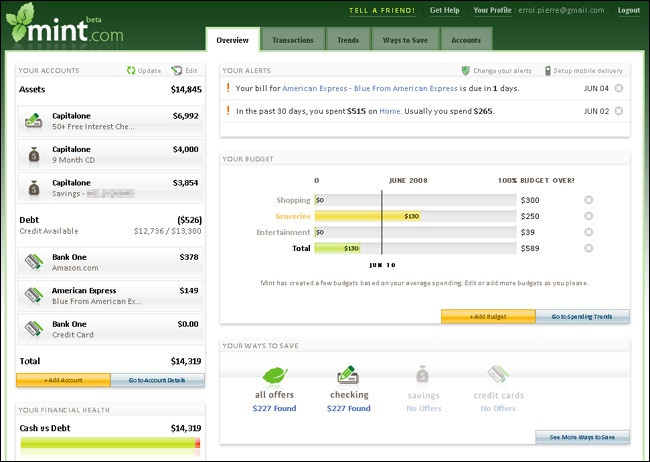

It was within that context that personal financial management software emerged. This category focused on building a dashboard of your assets across banks and investment accounts, largely screen-scraping data from websites or ingesting tax-related export files — yep, for Intuit and Microsoft software — to show you a budget of current holdings. Business models were in flux, and the main thing was to get users to show up in the first place.

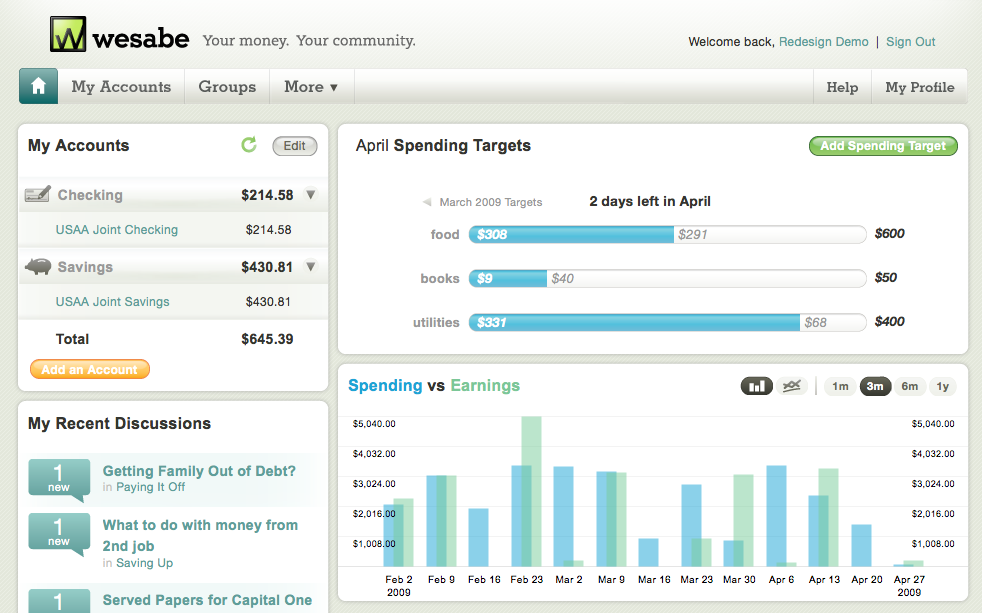

Mint.com was not the first entrant, founded in 2006, but it became the category winner. It competed most aggressively with Wesabe, of similar vintage, though their underlying philosophies differed.

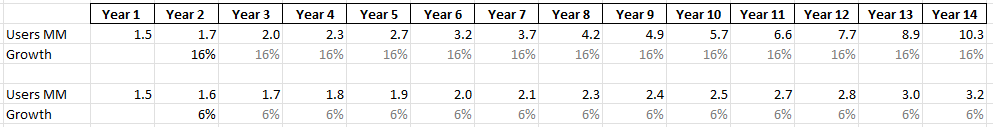

What you see above, in our view, is the sacred granddaddy of all B2C fintech. Before there was Bitcoin or Coinbase or Robinhood or Betterment or SoFi, there was Mint.com and Wesabe, drinking from the hose of your bank to give you a delightful Steve Jobs-level user experience. Eventually, Wesabe would run out of funding and lose to Mint, while Mint would be sold for $170MM in a hotly negotiated deal on around $10MM in revenue and 1.5MM users.

Every fintech SPAC in 2020 can be categorized as Mint.com with a financial product bolted on. But we digress.

Here’s what the founder of Wesabe said about the outcome:

Mint focused on making the user do almost no work at all, by automatically editing and categorizing their data, reducing the number of fields in their signup form, and giving them immediate gratification as soon as they possibly could; we completely sucked at all of that. Instead, I prioritized trying to build tools that would eventually help people change their financial behavior for the better, which I believed required people to more closely work with and understand their data. My goals may have been (okay, were) noble, but in the end we didn’t help the people I wanted to since the product failed. I was focused on trying to make the usability of editing data as easy and functional as it could be; Mint was focused on making it so you never had to do that at all. …

Between the worse data aggregation method and the much higher amount of work Wesabe made you do, it was far easier to have a good experience on Mint, and that good experience came far more quickly. Everything I’ve mentioned – not being dependent on a single source provider, preserving users’ privacy, helping users actually make positive change in their financial lives – all of those things are great, rational reasons to pursue what we pursued. But none of them matter if the product is harder to use, since most people simply won’t care enough or get enough benefit from long-term features if a shorter-term alternative is available.

There’s a lesson here for Web3 founders, focused on privacy and granularity, at the expense of just making the thing *work*.

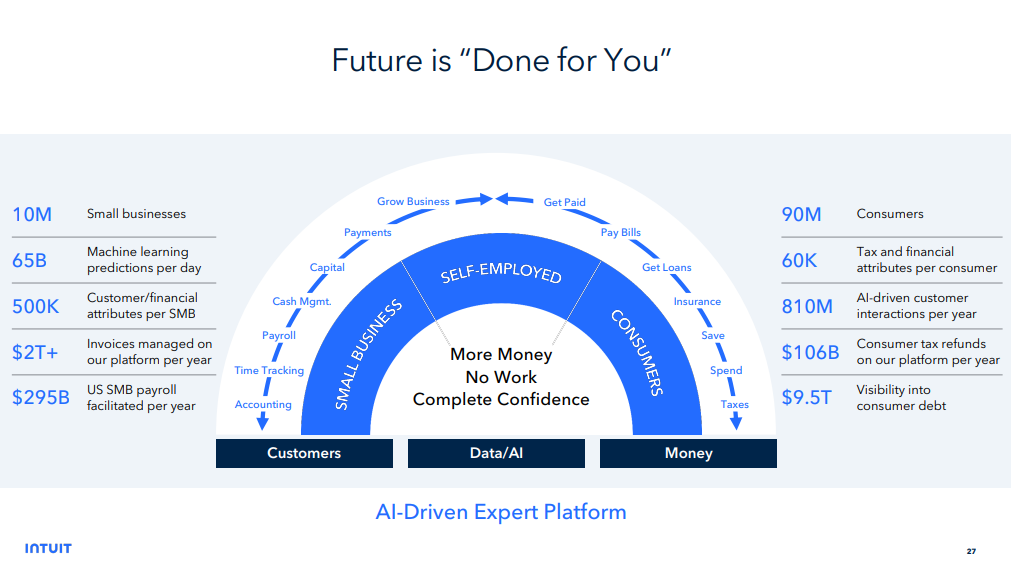

In an uncanny turn of events, take a look at Intuit’s positioning in the AI space. This approach has probably created more value for the Intuit than any operating metric from the acquisition.

But, while the DNA of Mint.com may have permeated Intuit’s investor presentations, its business results have not. In 2021, Mint had 3.1 million active users — not much more than the 1.5 million Intuit got in 2009. Generously, perhaps that translates to 10 million signs up. This looks like uninspiring execution for 14 years of market leadership.

To that end, Intuit is shutting down Mint.com at the end of the year, sending budget nerds scrambling to find a replacement PFM. But they won’t find a good free one, because, you guessed it, it is now pretty clear there is no good business model. Instead, users can migrate to another website that Intuit offers — Credit Karma.

A Better Mousetrap

So what is the existential mistake of PFMs? What have they done wrong? And how can it be fixed?