Long Take: Carta's misstep and exit from secondary markets point to a bigger problem

A lesson in the complexities of private equity

Gm Fintech Architects —

Today we are diving into the following topics:

Summary: Let’s talk about the Carta controversy through the lens of private markets. Should the company use its private cap table data to create secondary markets? We first explore the mechanisms of making money through cashflow or asset market value, and highlight the increasing trend of companies going public later, shifting enterprise value gains to private investors. Founders and professional investors often have significant control and protections in private companies, while employees usually hold a smaller stake with less control. The value of employee compensation through company stock is increasingly questionable, especially in private companies, where selling equity is complex. We argue for greater transparency and freedom for small shareholders, and explore how tokens can create better outcomes.

Topics: Amazon, Apple, NVIDIA, OpenAI, Carta, Nasdaq Private Markets (Secondmarket), Forge Global, Linear, Hedgey, capital markets,

If you got value from this article, let us know your thoughts! And to recommend new topics and companies for coverage, leave a note below.

Long Take

Enterprise Value

There is a magic formula that all finance people know.

You can make money from (1) cashflow, such as earning a salary or charging rent, or from (2) the market value of an asset, by selling a company, a house, or equity that has appreciated. In the first case, you are probably trading hours of your life in exchange for a wage. Usually, there is no residual value. One the gravy is gone, it’s over. In the second case, you are an owner building out an asset, for which there may be a market with supply and demand.

If lucky, your asset may become valuable and generate far more proceeds than cashflow alone. This is the job of capital markets, and their sorcery.

The middle path is to work for a company and receive some part of your compensation in stock. Some companies are public, and the equity you receive is immediately “liquid”, meaning it can be sold to others at the spot price. While it is possible to get filthy rich in this way — think Amazon, Apple, or NVIDIA — it is unlikely.

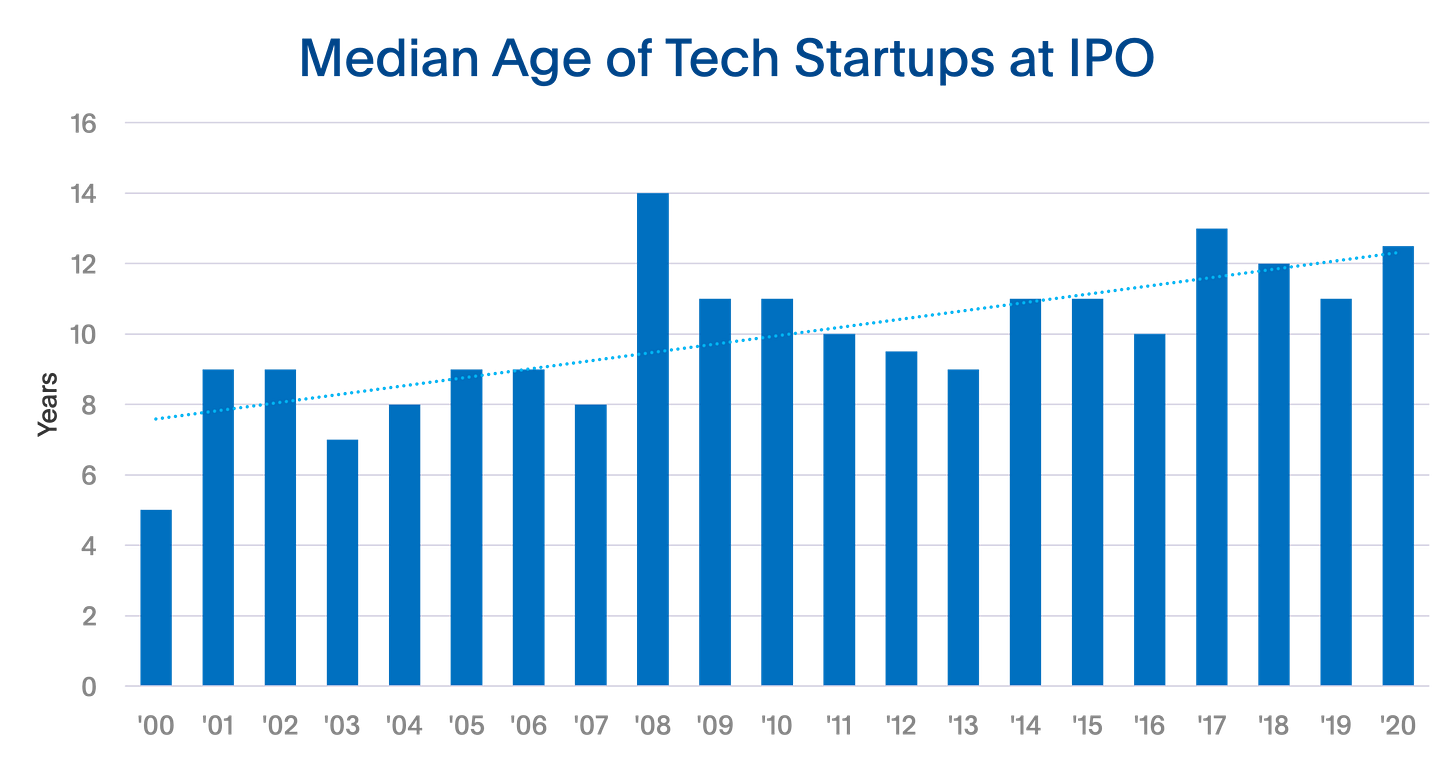

Companies have been going public later and later in their lifecycle. That means more of the enterprise value gains are going to private investors.

This leads us to ask questions about the private markets and their participants.

Most private companies will have (1) founder shareholders, who are running the company and have some amount of control, (2) professional investors, who have some board control over the management and legal protections via their share class, and (3) employees and other small options / common stock investors, who have no meaningful protections.

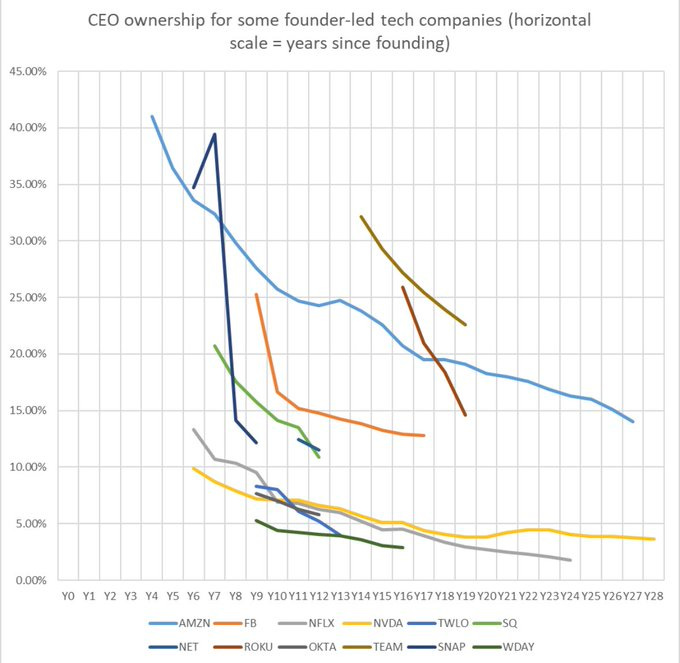

Founders stand to make a lot of money from successful exits — from single millions to hundreds of millions of dollars, given they tend to own 20-50% of the company.

Investors also purchase 10-20% of a company’s value per round. Not only is that sizable, but those positions likely have protections like drag along rights (if company sell shares, investor can force sell) or rights of first refusal (if shares are sold, they can be the first look). Not to mention preference (getting paid back first) and participation (getting equity sweeteners on top). This is not nefarious — just part of the capital markets, including the market of legal clauses on the sides of capital supply and demand.

How much then do employees have?

Per person, we are looking at 20 to 100 basis points out of a 10% to 20% option pool. The option pool is also likely to have a strike price at a “fair” valuation, most often the last round or a tax valuation. In the case of a $100 million company, this is probably a few hundred thousand in value — you have no control and are at the bottom of the cap table.

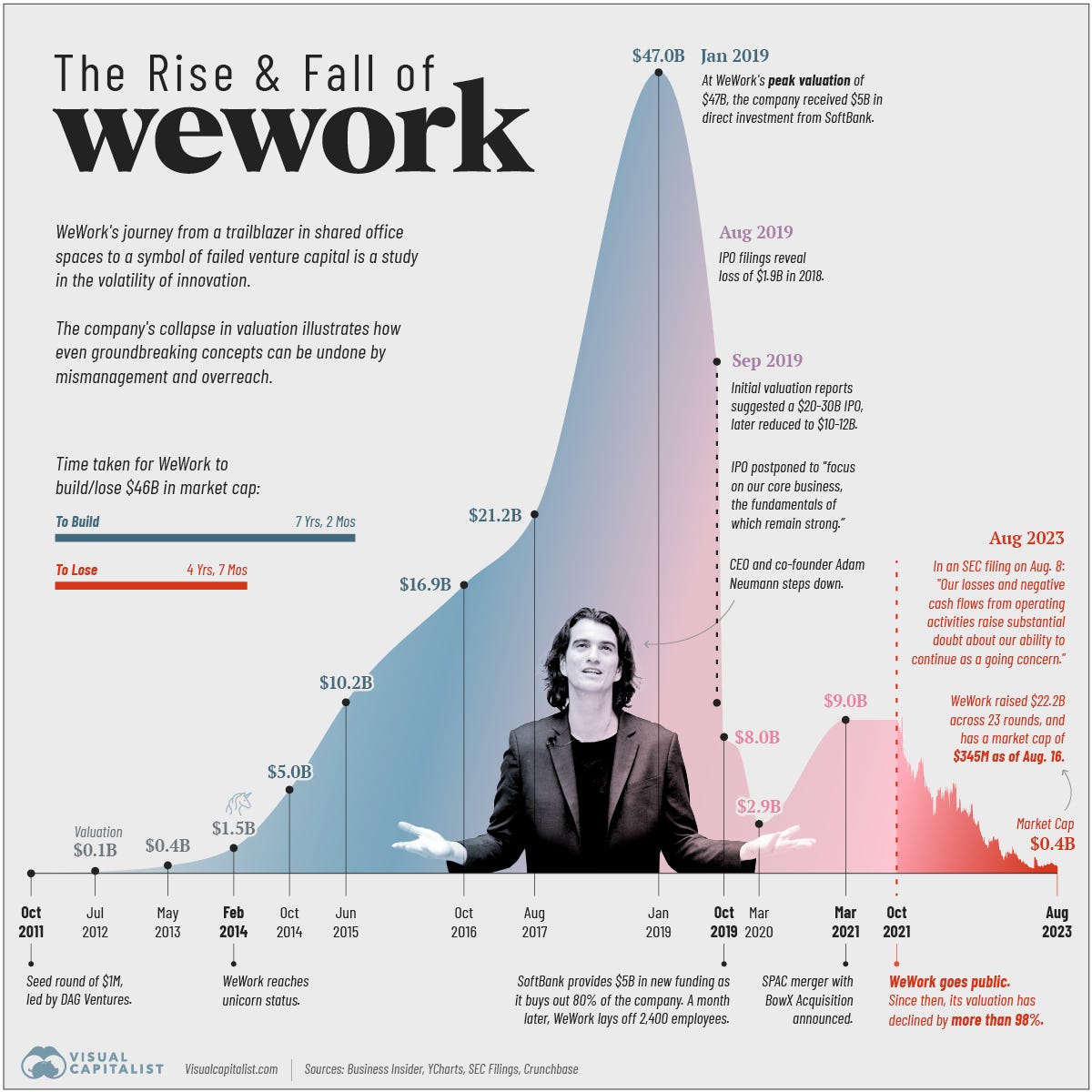

From a risk perspective, it is clear why this employee cohort of holders would want to sell first. Sure, founders and VCs want liquidity too, and are even more likely to negotiate their way to those outcomes. Just look at Adam Neumann and WeWork, with the founder worth $1.7 billion and the company in bankuptcy.

Unfortunately for employees, they have no negotiating power or legal priority. They cannot resort to public markets, and instead must hope for secondary private markets, where specialized investors want to purchase their shares before the company goes public. If you are OpenAI, this is a pretty lucrative deal still, if they hit the $80B valuation. Given the amount of value created, the company is pretty loose with allowing employees to sell. But in most cases, the company probably does not want employees to sell. Why?

There are a couple of reasons. First, a company wants to contain its narrative in the fundraising process. It does not look good for executives to be selling stock while the company is trying to raise money. The employees might be willing to sell for below the last round price, at a discount, which further degrades the impression of success, and hampers the ability to raise more. Further, employees that have sold off their equity no longer have long term incentive, and may be more likely to leave their roles for another position, unless the company refreshes their awards. All this comes together to create complexity.

And so you have a supply of private equity that is contractually locked in and subordinated.

But the idea of secondary markets for these interests is infectious, and is one of the core traps in fintech. Just like equity crowdfunding, it plays on the allure of private investment and getting lucky with early stage companies.