Long Take: Learning from SVB, Signature, and Silvergate, and unpredictable complex systems

Can we trust USDC and DAI?

Gm Fintech Architects —

Today we are diving into the following topics:

Summary: We look at the balance sheets of the failed banks, and find treasuries and mortgage-backed securities yielding 1-3% in interest. Our analysis examines the effect of holding these securities in a 5% rate environment, as well as tracing how these risks materialized in banks with a low share of retail deposits and a high share of business customers. We look at the cohort of related banks, which are now experiencing similar pressure, and the backstop built by the government to subsidize loans collateralized by these fixed income instruments. Lastly, we discuss stablecoins and the need for a digital dollar.

Topics: macroeconomics, fixed income, currencies, banking

Tags: Federal Reserve, Silvergate, Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, BNY Mellon, USDC, DAI, Ethereum, Bitcoin, First Republic

If you got value from this article, let us know your thoughts! And to recommend new topics and companies for coverage, leave a note below.

Long Take

Understanding your risks

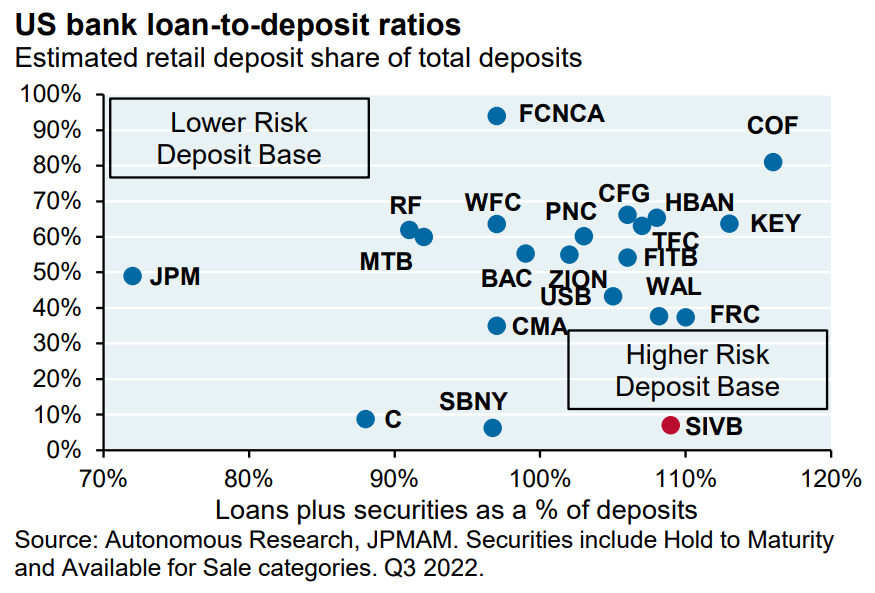

It’s no fun to be a bank stock in the US.

Just when you thought the high interest rate environment was here to give you some sweet net interest, instead your customers collapse and their investors initiate a bank run, throwing the whole thing into a tailspin with the government coming into the industry to save depositors.

We’ve written about Silvergate and Silicon Valley Bank in some detail, so let’s get those links out of the way and assume we can reference the concepts in those articles.

To financial professionals and bank analysts, a lot of these failures are predictable and obvious — in retrospect.

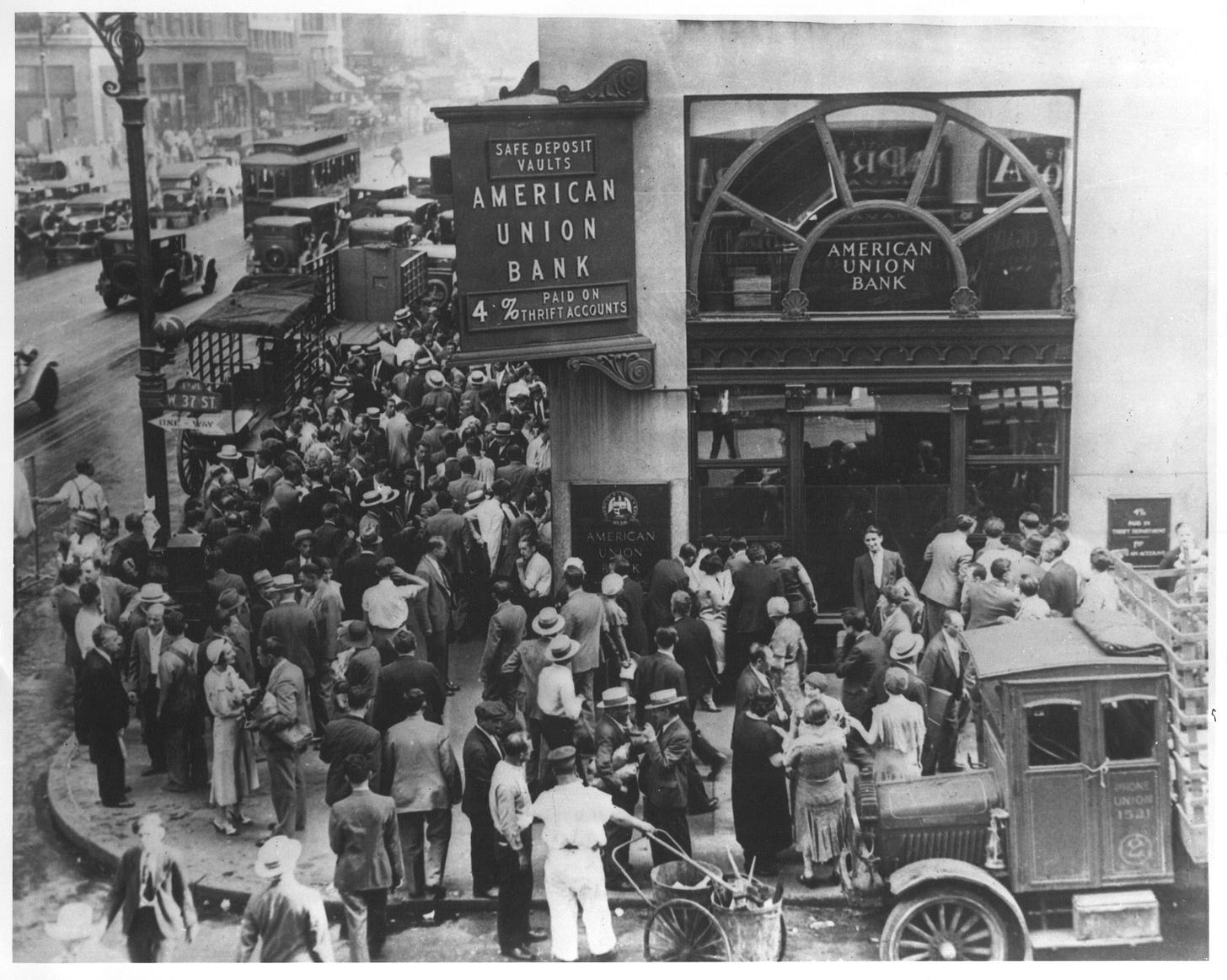

The primary claim is as follows. A bank takes in deposits (i.e., liabilities) and loans out those assets to generate a return which you occasionally see in your savings account (i.e., assets). It is the bank’s core job to match the duration of the assets and the liabilities, such that when people show up in a line outside of a bank to withdraw their cash, the cash is there to be withdrawn. That is literally job number one.

There is a tragedy of economic incentives with banks. The more people want to withdraw their money, because they feel nervous about the safety of their money, the more other people want to do that too, which in turn puts all of the money at more risk. This is called a bank run, and it can and will blow up any and every bank.

The reason for why is simple. Banks don’t have all the cash on hand — they lend it out! This is the “fractional reserve system”. They reserve only a fraction of deposits in order to transform the capital into useful economic activity, and generate rates of return.

The mechanics are not quite as simple as the ones pictured above. The way reserves are created at the central bank is to act as a capital buffer for the bank for withdrawals, and loans can be created irrespective of deposits on the balance sheet.

We can put the mechanics aside to reiterate the point that the money isn’t there-there. It is doing work. Instead of having the government select risks to underwrite, i.e., the central planning of the USSR, we have financial institutions evaluate local risks and underwrite them based on the machinery of capitalism, i.e., a good rate of return.

So if you are a bank, you are monitoring the risks to which your assets are exposed. One of those risks is to do a whole bunch of bad underwriting to bad businesses that go bankrupt — not something that is relevant to our current scenario. Another risk is to have interest rates rise and devalue your long-duration assets meaningfully — very relevant to our scenario. If you are a risk management professional, surely you have dozens of other such things to worry about. And further, you have solutions to these problems, like buying derivatives that protect your balance sheet from drastic interest rate fluctuations.

But you know, Lehman Brothers thought they were hedged too.

It appears that SVB and Silvergate, and maybe Signature, were not hedged, and again, analysts think this was an obvious mistake.

Complex Systems

It’s probably a bit reductive though to point to individuals and blame them for personal failings. Yes, this is a seductive way to think about things. There are good people, and bad people, and bad people do bad things, and then things are bad. What is much more likely, in our view, is that we are seeing a low probability outcome in a complex system.

What is a complex system? Here you go —

The economy is intertwined with itself, and the very many causal variables have circular loops that make exceptions highly unpredictable. People will call the banking crisis a “black swan” and other names for highly exceptional events, because it may have appeared unlikely in retrospect. But in complex systems, unlikely things are the norm. They surprise our small minds and narrow tools — this is a reflection on humans, not the systems themselves.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to model and get a grip on how these things work. But it also means we shouldn’t get obsessed with particular details to explain outcomes. Proximate, deterministic explanations like “why didn’t they just hedge out this exposure” misunderstands what it is like to be a person with limited capacity operating in a highly complex and multi-dimensional environment with no exits.

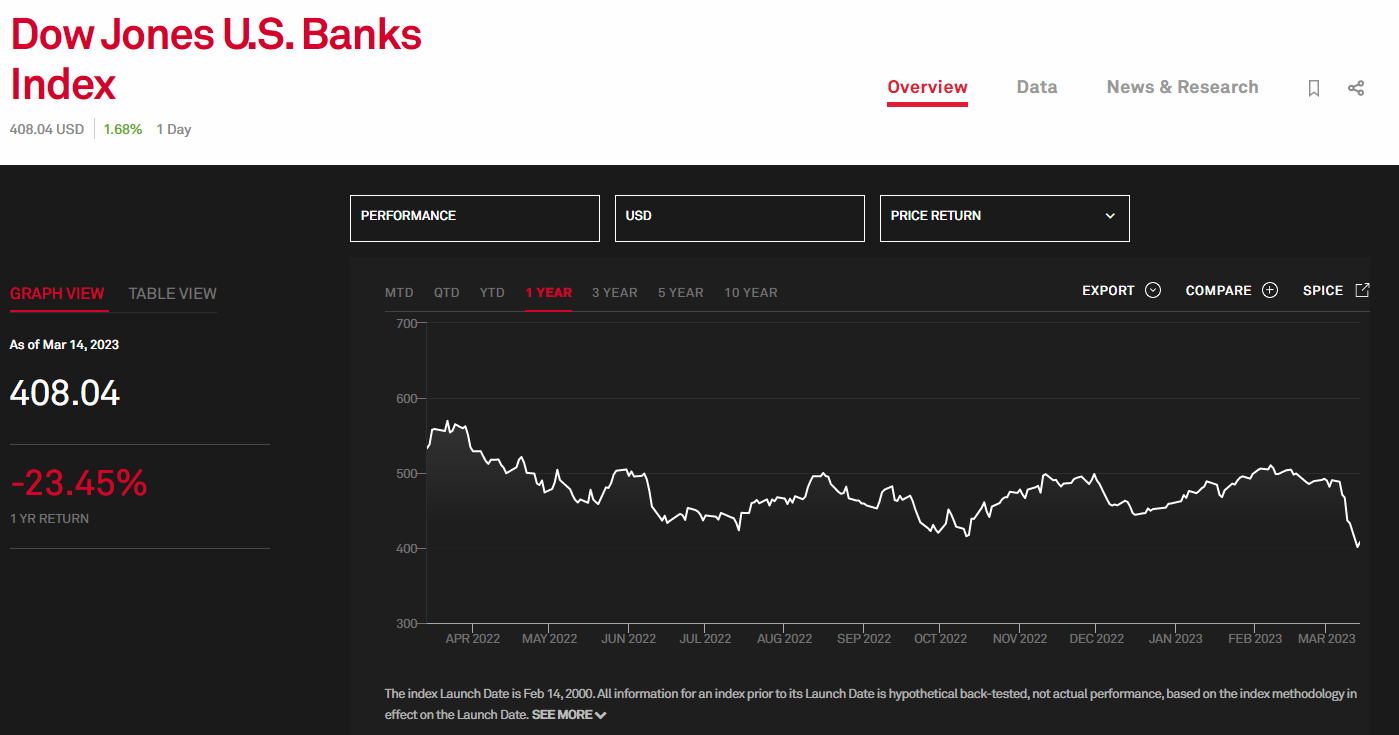

One of our favorite charts explaining the outlier nature of the banks that failed comes from, unsurprisingly, Autonomous Research. A simpler but less interesting version of the same point is below from S&P Global Market Intelligence.

What you can see in the chart is that the failed banks had one of the lowest percentages of retail deposits relative to institutional deposits. This matters because (1) retail deposits are more sticky and are harder to pull out of the bank all at once, since you need to coordinate more people, and (2) retail deposits are more likely to be fully insured by the FDIC $250,000 limit. In this way, banks that have big business customers that are all correlated to some sector — like crypto or tech — may experience a more dramatic run, and therefore should have more insurance, hedging, and liquidity.

But also, Citigroup is in this group?

The other dimension is loans plus securities (both held to maturity and available for sale) as percentage of deposits. This is a measure of how easy or hard it will be to cover a bank run. The more of the deposits deployed in underwriting, the more difficult it will be to cover withdrawals. So JPM is in a good position, and someone like First Republic (FRB) is in a worse position. Here’s today’s market assessment of these risks.

Note, however, that large banks like Citi aren’t really pricing these risks, because they are “too big to fail”. That means they have an implicit government backstop in case something goes wrong. Meanwhile, small regional banks did not have this guarantee up until the recent action. But since the government has stepped in, it has guaranteed to take as collateral treasuries, agency debt, and MBS and to issue debt to banks that need it, funding any withdrawal requests and removing the duration mismatch.

We’ve looked at the balance sheets of SVB and Silvergate before, so let’s pull in Signature bank, the last one to be taken down by the crisis to date.

Here you can see exactly the types of assets the US government is willing to underwrite — government and housing-backed loans yielding 1-3%. However, since market rates went up to 5%, the trading value of these bonds has fallen, down anywhere between 10% to 15% on their notional value. Thus the billions in paper losses.

Remember, all these debt obligations are going to pay out at par, at 100%. They will yield these low returns for 10 years or longer in the case of the MBS. That is a time horizon the government can absorb. And who knows, maybe in five years, rates will go back to zero again, and these securities will trade above par! In the case of the 2008 financial crisis, the TARP program was net profitable for the government in the long run.

We say all this, but go back to the complexity of the system. Let’s review:

The Fed prices interest rates at zero for over a decade, ushering in an era of cheap money looking for returns

The government prints $6 trillion during Covid to offset the effects of the pandemic, creating a risk-on environment of massive proportions

That money balloons personal savings, and drives investment into tech and crypto that created companies, who now had business savings

Those savings go back into the banks that served those segments, like SVB and Silvergate

The banks deal with the influx of capital by lending the money *back to the government* by buying up treasuries or agency securities, or underwriting investing in government subsidized assets, like housing

Inflation races up, further amplified by the Russian war and pandemic supply chain issues

The Fed cranks up interest rates to 5% — addressing neither the money supply nor the underlying economic fundamentals — tanking the valuations of tech stocks, risk-on assets, and … all those “safe” bond investments held by the banks, which are fully regulated and compliant financial institutions

The companies in question start failing and pulling money out, which leads to the sale of securities at lower valuations, which leads to the run, which leads to the government backstop

The government backstop values underwater debt-to-itself at par

The above is perhaps a bit naive and over-simplified.

For an even brighter caricature, we could say that the government printed money, which went into banks that then lent it back to the government, which then devalued those loans, and took over the banks.