Long Take: Wells Fargo $3B+ & Epic $520MM fines undermine positive-sum games and consumer surplus

May the robot overlord be with you in markets

Gm Fintech Architects —

Today we are diving into the following topics:

Summary: We paint a picture of a utopian economy, where perfect information leads to consumer surplus and positive-sum games. The analysis pulls apart a few fundamental ideas of fairness, and how they can be expressed in commercial activity, economics, and the fintechs and protocol projects that build them. We then dive into the enormous recent fines levied against Wells Fargo and Epic to understand the type of breach that occurred. Last, we discuss how such breaches are structural, and that a new economic architecture is needed.

Topics: economics, game theory, the law, governance, society, fairness, banking, metaverse

Tags: Wells Fargo, Epic, Apple

If you got value from this article, please share it. Long Takes are premium only, and we need your help to spread the word about how awesome they are!

Long Take

Right and Wrong

It is very hard to get people to agree about anything.

Well, the easy things, maybe we agree on. But the hard things, like whether the Earth is flat, or whether Elon Musk is a time-traveling war lord sent back in time to destroy the world, or whether using customer accounts to plug the balance sheet of your prop trading shop, are a bit more difficult. And once you get to the level of social policy, governance mechanisms like legislation and the courts are the best tools available.

We can resort to the tools of the economic accountant, or perhaps the more-in-vogue-now tools of the Bayesian AI scientist, and talk about utility. The Utilitarians would have us believe that people are economic machines with an abstract happiness dimension that can be maximized, and that pursuing choices that generate more utility / satisfaction is the hallmark of positive interaction.

This is sort of true, except it’s not, and has been proven false by behavioral economics, showing how people routinely make mistakes in choosing things that make them worse off. Also you get strange philosophical outcomes, like making one person supremely happy (+1000 utility points) while making a lot of people a bit miserable (-999 utility points) is still a thing we should do for net gain (+1 utility points).

Another way to go is something like the John Rawls veil of ignorance approach. It asks you what rules in the world you would like to have, if you did not know which position in the world you would take up — a judgment from behind a “veil of ignorance”. So, for example, as a successful billionaire, you may want certain rules removing protections around markets, banking, and gutting social welfare. But, if you had a high chance of being born into poverty in the developing world, for example, you might design different rules to insure yourself in case you end up disadvantaged.

The Rawlsian approach manipulates us into optimizing for the good of the most disadvantaged people in society. It uses our desire for self protection to create ideas and rules that resemble justice.

Creating Fair Value

This takes us to some recurring themes in Crypto, but also in economic exchange more generally. Why does anyone exchange anything with anyone else? What value comes from markets and capitalism? What do economies “clear” that is good for everyone? There’s a lot of sophisticated work on the topic of Pareto efficiency, and so on. Here, we are talking more simply about consumer and producer surplus.

Let’s say you would pay $10 for a sandwich, but are only charged $5. That is a whole $5 of value that has materialized out of thin air! Someone else might only be willing to pay $5, so they do not experience this bounty. But lucky for you, you feel the amazing feeling of getting both what you want (a sandwich) and a great deal (the consumer surplus).

Similarly, for the sandwich maker that makes the sandwich for $2.50 and sells it for $5.00, we get economic profit on the margin! This is producer surplus, and together with the customer, we have created the utility of free choice. Markets aggregate and clear these preferences. If they are not perfectly competitive, and there are monopolies controlling a side, or if the demand and supply curves are shaped in particular ways, then the surplus might not be fairly distributed. But some is likely created through free exchange regardless.

Note that here we have to assume both buyer and seller have the same information, about themselves, each other, and the goods in which they are transacting.

We can handicap the welfare both parties get by saying that maybe the seller lied, and sold a sandwich that the buyer thought was delicious, but was in fact gross and yucky. Clearly the buyer’s willingness to pay earlier on would have been lower. Therefore the deception is theft. In contract law, this would be called a failure to have a meeting of the minds, and creates damages you can sue for in court.

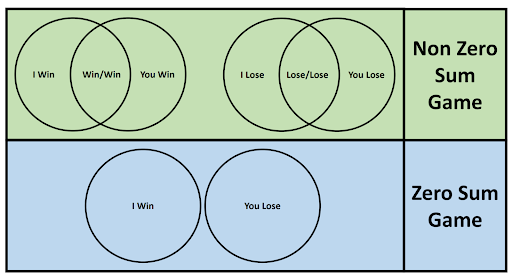

Another idea that seems to be floating around a lot is this idea of “positive sum games”. This comes from the language of Game Theory, which studies the dynamics of interactions between various market participants, occasionally over time. A zero-sum game is one where there is a fixed pie of benefits, like market share of profits in the newspaper industry, and the players — newspaper firms in this example — compete with each other to slice up the pie. Whatever one wins, another one loses.

One could make the argument that Web2 was a zero-sum game in that users lost their data, choice, and privacy, and that Web2 companies received advertising revenue in exchange. We don’t fully agree, but it can be a topic of debate. Now a negative sum game is the worst of all cases, whereby playing you erode the rewards of the game.

This leaves us with the idea of a positive sum game, one where all participants in the game could be theoretically better off. Take, for example, everyone in some part of the tech industry that is about to grow exponentially. Each venture investor, each start-up, each software user, all of them are better off for having contributed time and effort to building things in that particular niche. Instead of competing with each other, players can cooperate to reach the most ambitious result.

Web3 thinkers like to point out how the Web3 version of the Internet is built on the idea of being non-extractive and therefore a source of value of consumers. By sharing governance and ownership through tokens with users and community, incentives are created to drive collaboration and coordination amongst all the stakeholders of a particular project. Everyone is better off growing the communal pie, instead of trying to short-cut value extraction from customers or developers.

It’s a great story. Unfortunately, experiments like Olympus DAO have shown how such a narrative can be adopted exactly for extracting value from people who believe in cooperation, but end up having their assets destroyed through ponzi mechanics. This again was a problem of asymmetric information — if users knew and understood what the financial engineering of Olympus would lead to, likely they would have behaved differently.

Still, we admire the idea of voluntary, well-informed, positive sum contribution, in the same way we admire the consumer surplus created from voluntary, well-informed, fair commercial exchange.