Long Take: Understanding the fall of FTX and attempted acquisition by Binance

The world is on fire and your money is the fuel

Gm Fintech Architects —

Today we are diving into the following topics:

Summary: Another day of fires in the world of crypto exchanges, as FTX seeks an acquisition buyout from its rival Binance. In this analysis, we walk through the various ways that financial and capital markets companies fail in order to understand what is likely to have happened with FTX. We talk about leverage, liquidity crises, bank runs, comingling of client assets, and proprietary trading. Lastly, we highlight the systemic risks still present in the markets, and their potential scale.

Topics: capital markets, crypto, exchanges, brokerages, digital investing

Tags: FTX, Alameda Research, Binance, Coinbase

If you got value from this article, please share it. Long Takes are premium only, and we need your help to spread the word about how awesome they are!

Long Take

The Ways Financial Companies Die

Welcome to another exciting edition of “Watching the Slow-Motion Financial Crisis”. Today’s episode is called “Unmitigated Disaster”, brought to you by Crypto Twitter.

In this episode we are going to remind you about how things break, and then try to figure out what could have happened with FTX, such that it had to sell itself to its best frenemy, Binance. Put another way, why would an industry dominant exchange with a $30-40 billion valuation, that has been hoovering up distribution footprints across the industry, end up on the chopping block, with the knife held by its largest competitor?

Before we dive into diagnosis, let’s map out the territory.

Assume some sort of economy where productive activity happens. You make a sandwich, a customer buys the sandwich. That GDP, composed of revenues and economic surplus, flows through to people and businesses, and the people within the businesses. That group of investors now has assets that they would like to save, invest, and otherwise grow. Such growth can happen according to various objectives, and those objectives map to different types of financial manufacturers.

Most investors interact with financial markets through brokers and distributors. We can also call them financial advisors, or bank branch staff, or mobile apps. There is a divide between the store in which you buy financial product, and the factory that makes it. The manufacturer accesses different capital and financial markets and venues in order to transform the capital they receive as input through risk transformation.

A depository institution like a bank may change your cash into lending to local businesses, guaranteed by FDIC insurance. You are exposed to fixed income underwriting and credit risk, but your principal is protected. An asset manager or a hedge fund may invest your capital into equities or derivatives, and generate returns as such. Here’s a very abstract visualization of the above.

Let’s start with the first way things can fail out.

It is 1994 and you are Long Term Capital Management, a hedge fund trading fixed income. In fact, you have the best people in the world writing algorithms to trade bonds, in such a way that you think the trade is fully hedged and riskless. So you start to lever up your “riskless” trading up, and up, and up, all the way to 25x your actual position. And then various currency crises hit, and your Noble-prize winning algorithmic model doesn’t account for these black swan events. Wall Street bails you out to the tune of several billion dollars, but you keep losing money. And voila!

You can see in the diagram above there’s a new player called a lender, which provides additional capital in the form of leverage to the asset manager. The asset manager then increases their exposure to the capital markets. That exposure has to be paid back — often through a margin call to cover some particular position. Investors are also the ones that are providing capital to the lender, which is another form of manufacturer of financial products (e.g., margin returns vs. investment returns).

So when LTCM blows up from a down-move in the markets, they fail to pay their lenders, the Goldmans and Morgan Stanleys, who will do their best to try and bail out the fund. LTCM also fails to pay back their original investors. Investors suffer from losses in both investment products, have less money to spend in the economy, and so on..

This should look exactly like Three Arrows Capital to you (👑 our coverage here). 3AC had a lot of crypto assets, then levered itself up with very loose credit guidelines from firms like Voyager, Genesis, and others. It then lost that money in several degen YOLO bets. Here’s what it looks like when you’re about to default on your leverage:

Here’s another one like it from Celsius.

And here’s the fateful SBF tweet.

Now, let’s show some nuance. Celsius, a centralized investment manager pretending to be a DeFi distributor, did something different from LTCM. This is where regulation is important, as is good behavior — let’s call it being a fiduciary, which requires putting client interest above that of the firm. Alternately, just not doing fraud is pretty good.

The company created the impression that it was taking customer deposits to invest in safe instruments. Yield on USDC would be a reasonable example. It positioned itself as an alternative to a bank account, thereby earning an investor some reasonable interest rate. But underneath the hood, the company ran an investing book and outsourced investing activity to anonymous third parties, and also ran a lending book, underwriting pretty crazy strategies. At the end of the day, all of the capital markets exposure was tied to crypto market prices, and in particular Terra.

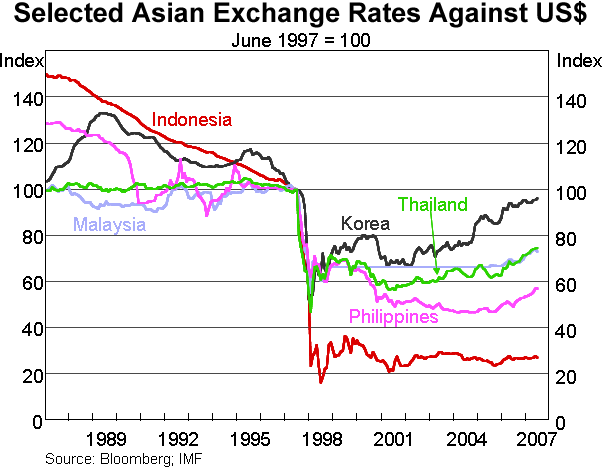

Terra’s collapse was the black swan event kicking off the party, similar to the Asian and Russian currency crises in the case of LTCM (👑 our coverage here), some of which fell as much as 80% — and that’s for operating economies. Terra had the beginnings of an operating economy, but its recursive stablecoin mechanisms and ponzi-like liquidity magnets, like Anchor, outweighed any productive entrepreneurship.

Okay, here’s the last element we need to describe — the confidence crisis, the liquidity crisis, the bank run.