Building Company Playbook #8: Dangers of the Growth Hacking Dark Arts

From Fake Growth to Ghost Networks in Web3

Hi Fintech Architects —

Today we are continuing our Building Company Playbook series, targeted at addressing the key questions in getting Fintech and DeFi projects off the ground.

This entry will focus on how some companies exploit metrics to create an illusion of growth, distorting their real value and deceiving investors. Tactics include shifting profitability projections, using misleading engagement metrics, or fabricating user activity through click farms and bots, a practice prevalent in both Web2 and Web3 spaces. In crypto, wash trading and inflated metrics like Total Value Locked (TVL) artificially boost perceived activity, while incentivized engagement—such as airdrop farming—leads to ghost networks once rewards dry up. These deceptive tactics, as seen in cases like WeWork and FTX, ultimately undermine genuine resilience and sustainable business growth.

For prior series, here are the guides so far:

To support this writing and access our full archive of newsletters, analyses, and guides to building in the Fintech & DeFi industries, see subscription options below.

Long Take

Fake it till you make it

The world is a competitive place, and not everyone plays fairly.

Today we are diving into a particular set of dark skills that — when used unscrupulously — create the illusion of winning. Sure, the idea of “fake it till you make it” can sometimes help a business bridge the gap between vision and reality. It certainly helps you raise venture capital. Various systems push people to behave in ways they would never otherwise consider, if it weren’t for the incentive of a unicorn valuation from SoftBank.

But there is a fine line, and crossing it leads straight into fraud and deceit. So think of the below not as a guide on how to cheat, but on how to spot the cheaters. As Web3 and Fintech rebound in the market, we are having more and more trouble telling truth from misinformation.

Here be dragons.

The Misdirection of Numbers

Most companies have to build financial projections to raise capital. Those projections are supposed to represent the reality of the company, and the best guess as to how it will succeed. But this can be abused.

A classic move is pushing profitability perpetually into the future. Every year, projections paint a rosy picture where profits are just over the horizon. And every year, those projections are just moved out by another year forward. By shifting the timeline for profitability, companies convince investors about potential financial strength even as underlying fundamentals remain weak.

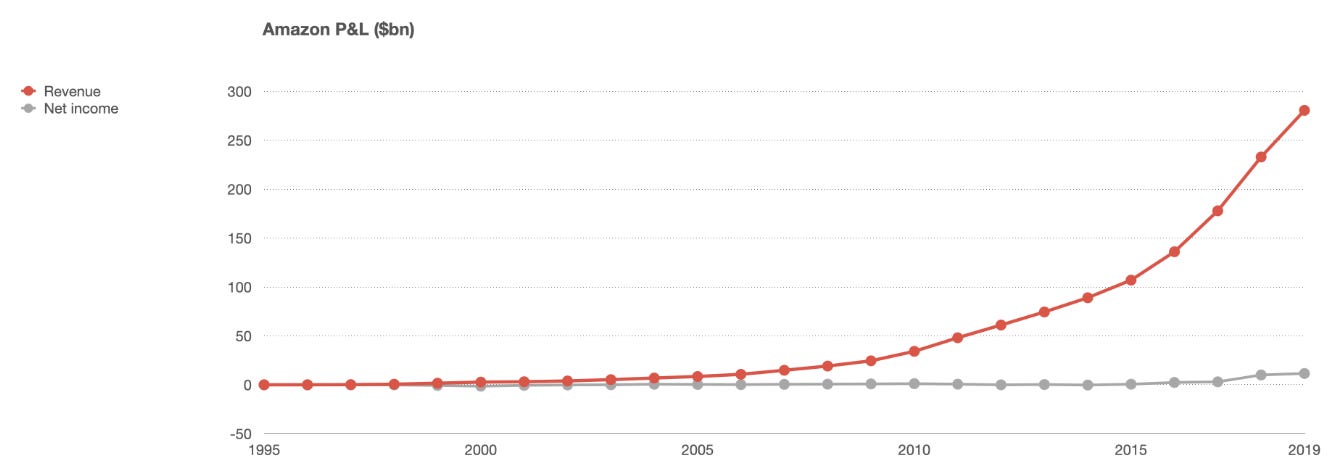

This abuses the Amazon example — a company that was deeply unprofitable until it achieved massive scale and generated remarkable outcomes. But not all companies must invest in national infrastructure like Amazon, and for most, their variable costs will stay variable.

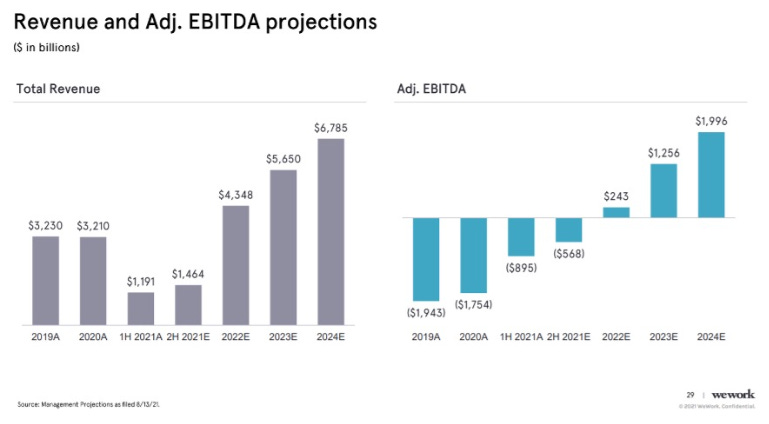

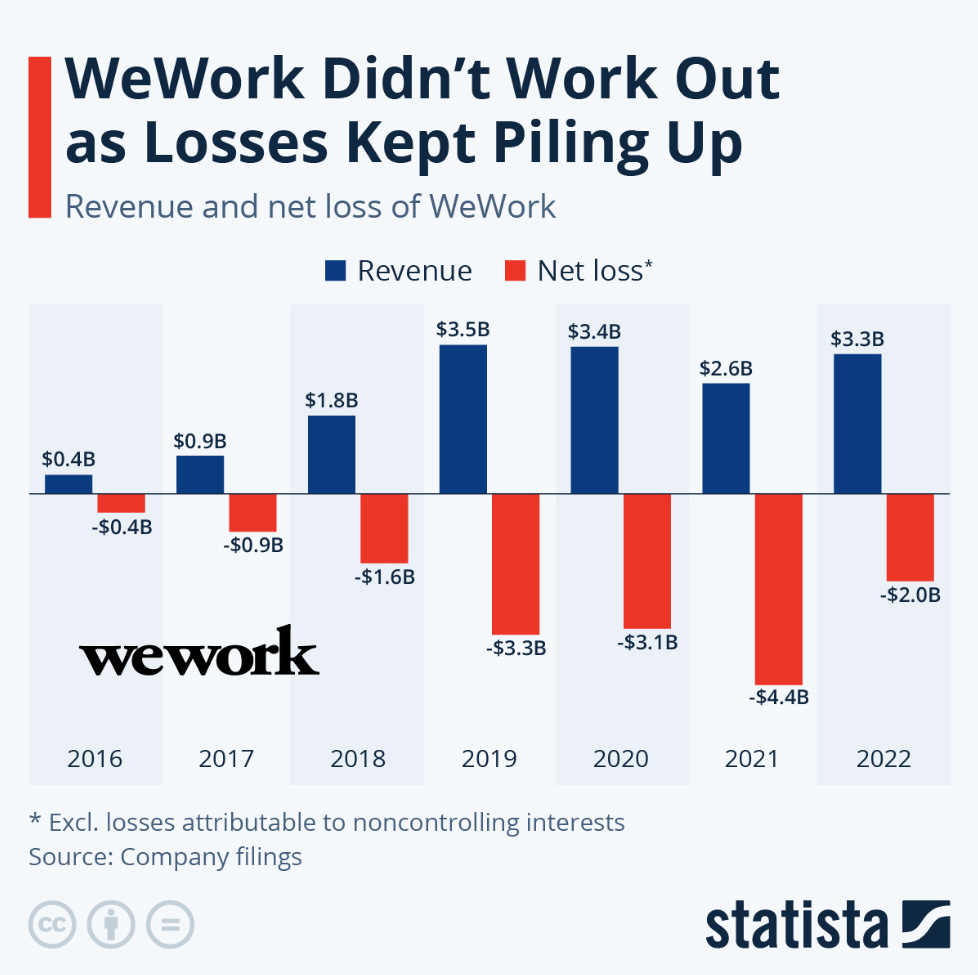

WeWork’s infamous IPO debacle is a textbook example.

With a sky-high valuation of $47 billion, WeWork sold a vision of a “transformative” real estate company destined for massive profitability through global expansion. Yet, when you peeled back the layers, WeWork’s actual finances were bleeding, and it became more unprofitable the more it grew.

WeWork’s valuation plummeted from $47 billion to bankruptcy.

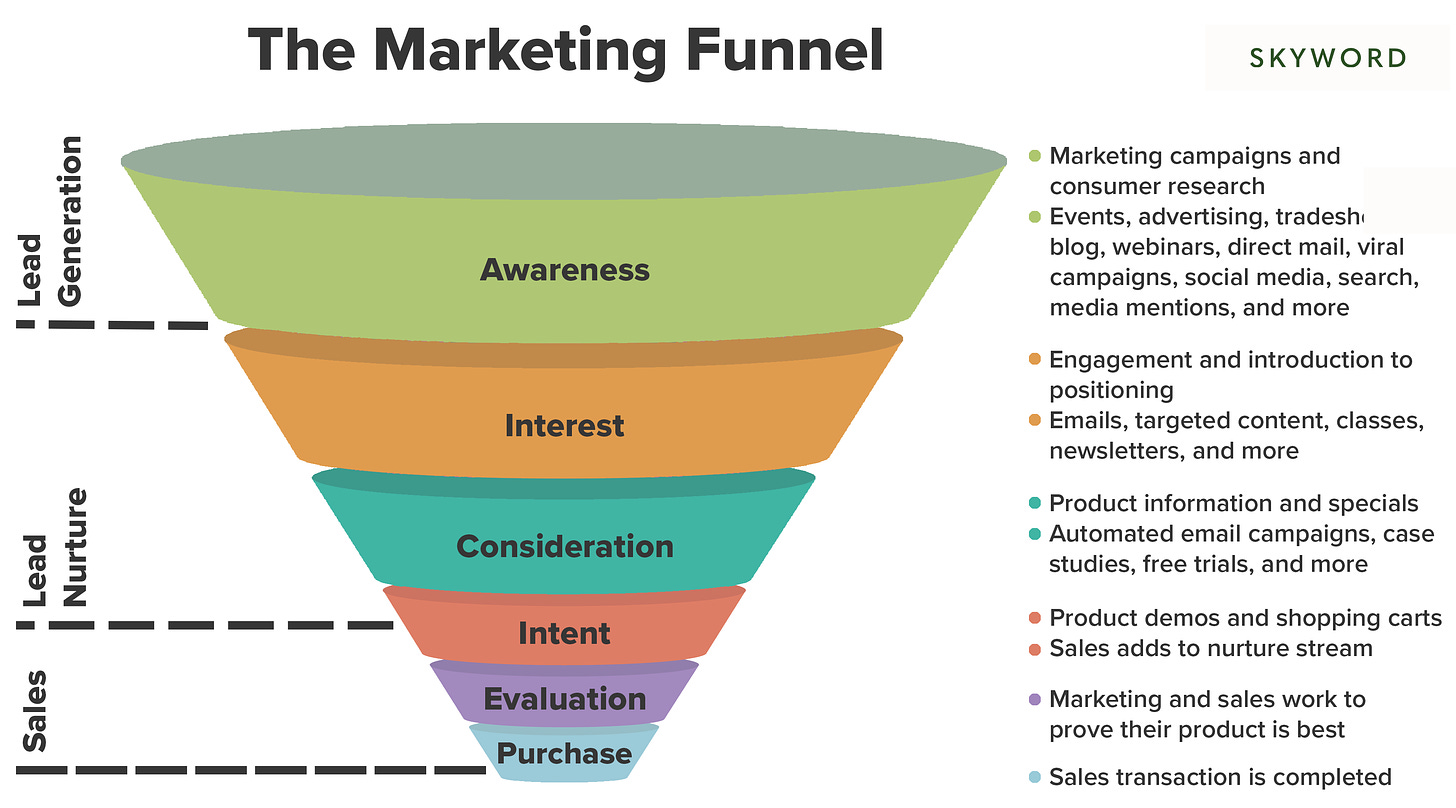

Another way to misdirect with numbers is to shift focus to alternative metrics that paint a friendly picture. Sure, KPIs like “user engagement” or “brand reach” can matter — if they are tied to revenue. For public companies, the games are usually about accounting and adjusting EBITDA such that they paint a friendly story. For startups, EBITDA is not an option. Instead, we move up and down the below funnel, relying on the fact that most people do not have an intuition for the chance of a user turning into a paying customer. Hint — it’s not 20%, but 0.20%.

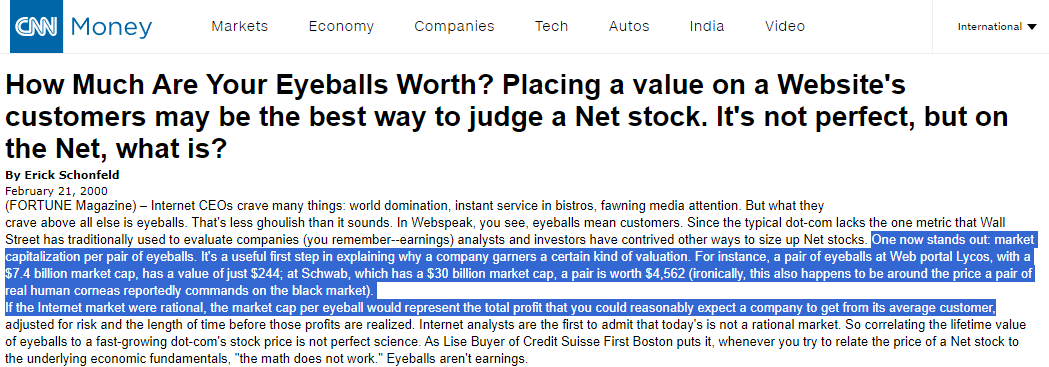

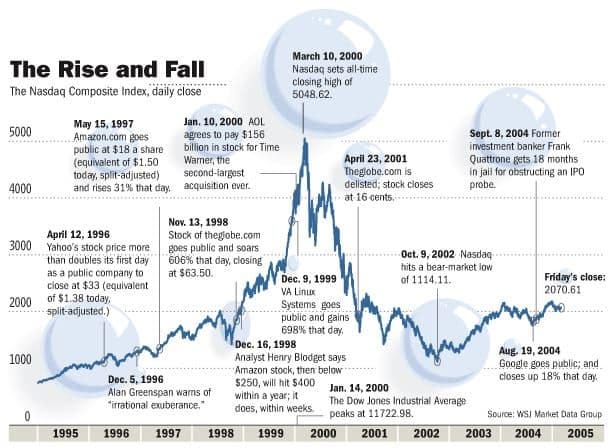

One famous example is the over-valuation of startups during the late 1990s. In the dot-com bubble, tech companies hyped user engagement — eyeballs — as a substitute for actual revenue. The idea was that high traffic would eventually turn into profit. According to a CNN article from 2000, Schwab traded around $4,500 per visitor, while Lycos traded at $250 per visitor. Remember, these were not revenue numbers but somebody visiting a website to consume free content.

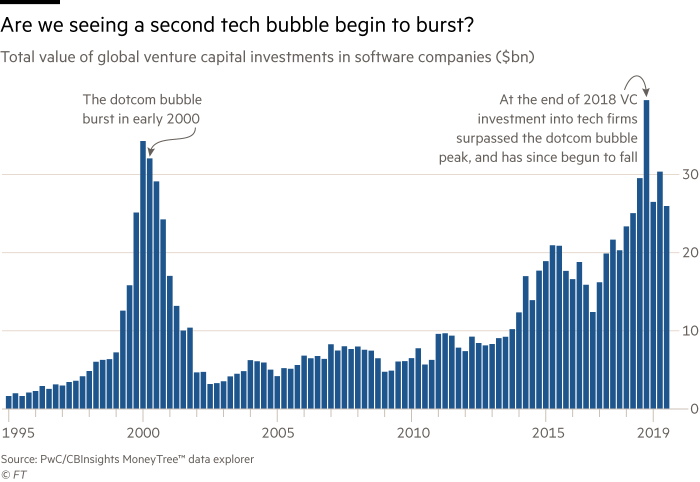

When revenues didn’t materialize and the bubble burst in 2000, companies touting engagement-only metrics took massive hits, losing an estimated $5 trillion in market value.

Today, things are even worse. Companies can buy email lists and market them as “sales leads” or focus on campaign numbers rather than the results they deliver. For instance, “registered users” may include anyone who signs up for a free trial, with no plan to buy. These tactics skew real engagement, leaving us without a clear view of actual demand. In the extreme, some companies just manufacture fake emails and defraud investors. JP Morgan was recently fooled into purchasing a company that made up all of its users using synthetic data.

Growth Hacking Gone Fake

Real growth takes time, and sometimes, companies don’t want to wait long enough to grow organically. Instead, they turn to growth hacking — the inauthentic kind that fabricates user numbers and trading volume to create an illusion of traction.