Long Take: Why $ billions are flowing out of Banks into Money Market Funds, and how startups can benefit

$100-500B in deposit outflows per quarter from commercial banks, $40B weekly inflows into MMFs.

Gm Fintech Architects —

Today we are diving into the following topics:

Summary: In this article, we delve into the complex perceptions and impacts of interest rates in the financial ecosystem, emphasizing their influence on the fintech and crypto sectors. Detailing the shift of assets from bank deposits to money market funds (MMFs), we suggest this transition has been propelled by better returns and flexibility offered by MMFs, alongside evolving fintech integrations which facilitate easier asset movement. The piece also discusses the implications of these shifts on fintech companies who are integrating cash returns into their products, pointing out regulatory considerations and the role of innovations like tokenization in blending traditional finance with emerging financial technologies. Lastly, the article urges fintechs to focus on aligning their products with the real-life goals of their customers, instead of merely offering investment returns.

Topics: banking, capital markets, interest rates, deposits

If you got value from this article, let us know your thoughts! And to recommend new topics and companies for coverage, leave a note below.

Long Take

Collecting the Points

Let’s talk about interest rates.

Depending on your background and where you sit in the mighty economic value chain, you will have a different view of what those words mean.

To some, interest rates are a toggle set by the Federal Reserve in the great factory of the economy. They think of markets, capital flows, and the manufacturing of equilibria. If rates are just an abstraction of internal machinery, then you probably work in finance and may have lost the forest for the trees.

To others, interest rates are spending points to collect or be collected. If you are a bank, you are collecting points from treasury yield. If you are a bank account holder, maybe you are getting money points from your deposits. Or alternately, if you are a borrower, you must pay these points to access credit, and therefore have less wealth, and less ability to reach beyond your limit — real estate feels more expensive, for example.

To a quant, perhaps interest rates are embodied and measured risk, reflecting a weighted profound truth about how likely things are going to happen. This group over here may default on average at this rate. Insurance to cover that risk will cost this rate, as determined by the market, and so on.

If you are a fintech or crypto B2C startup, you might think of rates as product features. Adding yield to your cash account might be a way of adding new revenues streams, or acquiring new customers. You might race to integrate some embedded finance bank API, or floor your marketing team with value propositions of investment returns.

All these things sound different, but they all refer to the same subject. That subject is like the temperature, and we should be careful in how we think about the temperature. It is not the same thing to say that it is hot outside, and also that we want to go to the beach. It is not the same thing to say that it is expensive to borrow money, and also that we want to sell our house. Also, it is an artificial temperature that we invent — it is hot now, so that it will be cold later.

We bring up this long explanation to remind the reader that rates are a means to an end, and that that end is actual demand — the aggregated individual desires — of millions of people.

People don’t want money, or the earnings potential for money, just because of the number itself. They want it in order to achieve their actual lives, buying goods and services, creating financial security for families, or getting an education.

To that end, all that machinery going from the Federal Reserve to the fintech wallet is there for a customer that wants to increase their spending power for some real goal.

Don’t sell investment returns. Sell what those investment returns help your clients achieve.

Having spent this time reminding you of customer centricity, let’s look into the machinery of how capital — representing the demand for additional spending power — flows into the containers of yield. Thereafter, we can think about how those containers can then be implemented across distribution footprints, and made accessible to people.

The Products

Previously, we had discussed the Apple packaging of Goldman Sachs interest rates here.

Since, the “risk-free” return of the US dollar has risen to about 5.50%. The US government is willing to pay lenders this much to take their money off the market, contract the money supply, and lower spending and inflation. Or so goes the formula.

If you get that for free with the American sovereign, then everything else — the riskier everything else — must be even more lucrative, offering higher rates. Note, however, that the individual is generally going to struggle to get exposure to this 5.50% unless they find the right instrument. Similarly, treasuries of small and large business will be looking for these yields. All in, we are looking at somewhere around $21 trillion dollars of M2 money supply, which would love to partake.

One would assume that bank deposits are the place where you could access these rates. And in part, that would be right. If you are a chartered depository institution and have a Federal Reserve master account, you as the bank would be getting 5.40% on assets held there. That’s great, but most of us are not chartered banks. And those of us that have accounts at those banks do not necessarily enjoy high interest or even liquidity.

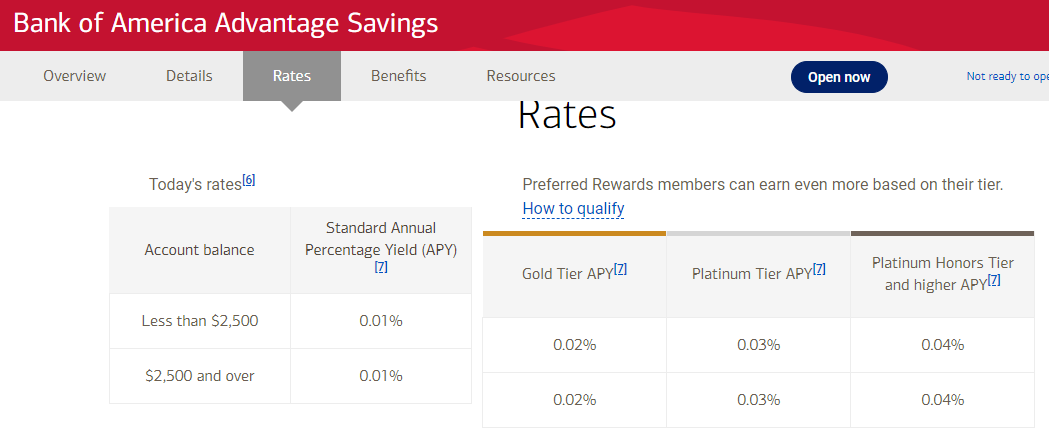

As an example, here is Bank of America and its Savings account and CD products —

If you want liquidity, meaning you can pull money any time from the account, you will be earning 2-5 basis points. If you start locking in your money for long term certificates of deposits, then your rewards will look like 3.50% to 5.00% in return. Why is this the case?

Well, banks don’t just hold reserves in the Fed account. They also lend out the money you give to them to finance mortgages, small business loans, personal loans, and all sorts of other credit-based economic accelerants. While that might mean the rates of return on those loans are higher than the risk free rate, it does not mean that the bank has your money. Rather, it means the banks definitely does not have your money. This is the core of what happened with Silicon Valley Bank. They did not have your money, just extremely safe long-dated government securities that were trading below par.

So as a bank customer, you are not getting either the "market rate” nor the immediate liquidity that you probably are expecting.

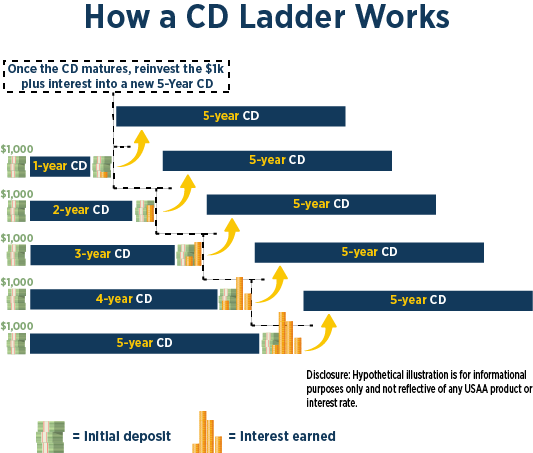

There are intermediate bank products, like CD ladders. These are certificates of deposit at banks, usually brokered by someone like Fidelity, that can create liquidity windows. For example, you might have rolling CDs that mature every 3 months. And perhaps they are from different bank issuers, which allows you to use the $250,000 FDIC insurance limit across a larger amount.

Above, you can see the example of a CD ladder with today’s rates. Future expectations see rates decreasing, so the 5-Year ladder generates less than the 1-Year ladder, which floats after the 3 month period. This product isn’t too complicated, but you can see already the outlines of counter-party risk and complex mental gymnastics.

Product Quality and Deposit Flows

Recent news shows that depositors aren’t particularly loyal to these bank-centered options, especially as the banking crisis exposed the fragility of the overall system.

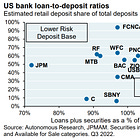

Further, with the divisions between banking and capital markets blurring, erased in large part by automation and fintech integration, money can move fairly easily to better form factors. And here is the evidence: