Hi Fintech futurists --

This week, we look at:

Coinbase planning to go public, and reverse engineering its economics based on publicly reported data and some educated guesses

If you want to tinker with the model, download it here

For more analysis parsing 12 frontier technology developments every week, a podcast conversation on operating fintechs, and novel food-for-thought essays, become a Blueprint member below.

Long Take

Coinbase is going to go public.

The news hit Reuters, then Coindesk, and then the rest of the world. It feels like big news! The crypto broker is beating Robinhood, Acorns, Stash, Revolut, Betterment, and Wealthfront to the public markets. It's even beating SoFi, which is trying to get a national bank license (and who doesn't want to own a bank!).

It is, however, behind Lemonade, the insurtech that raised $300 million and saw its market capitalization increase from $2 billion to $4.5 billion on revenues of about $50 to $100 million.

Like many modern tech firms, Coinbase will likely avoid investment bankers and do a direct listing -- maybe even do a digital securities offering instead.

So in the spirit of curiousity, we busted out the spreadsheet. As operators, we want to know how to build the economics of a multi-billion dollar behemoth. Obvious disclaimer -- this is not investment advice, not that any of us can act on that. And, we don't have any information about Coinbase other than what a quick Google image search brings up. That means everything we model is absolutely wrong and based on a made up premise. So let's see how the sausage could be made.

Revenue Build

It's hard to find real revenue numbers for a private company. There's an incentive to let reporters say that revenues are high, and not correct them.

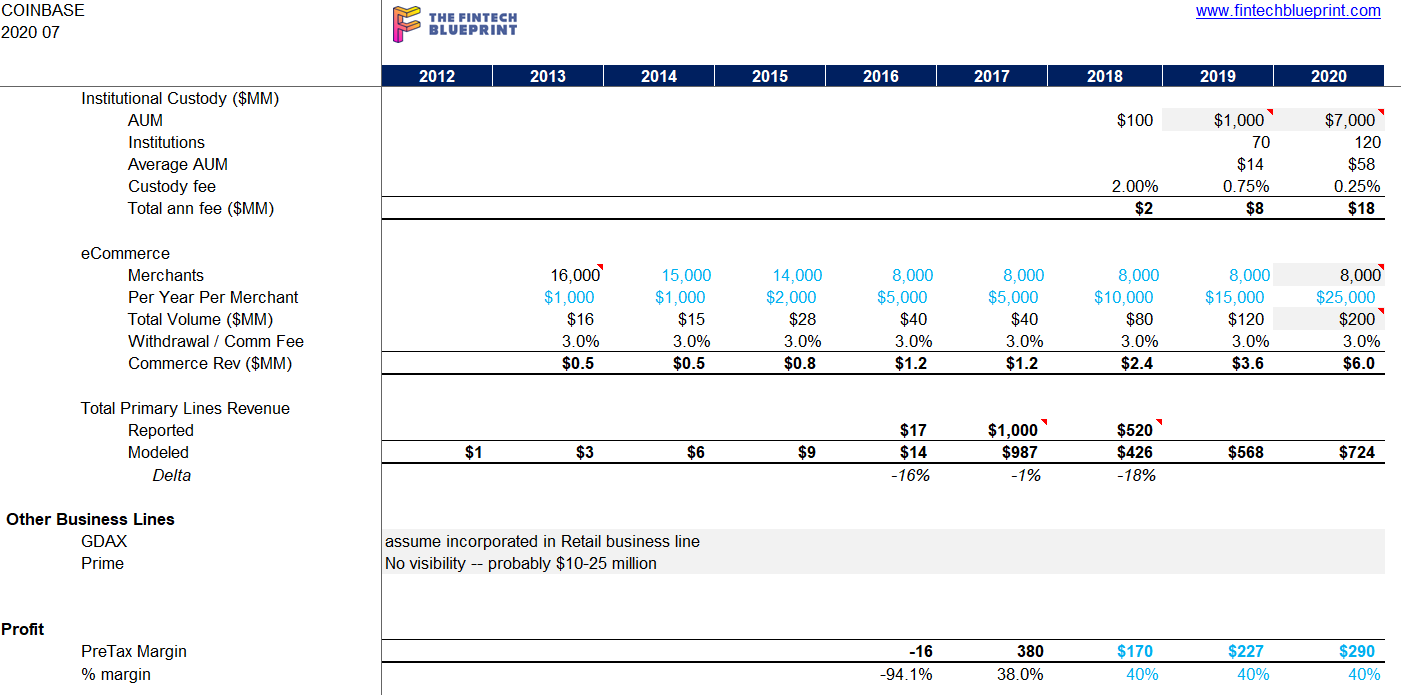

We have a few $1 billion revenue articles floating around, most of which are anchored in 2017 crypto mania. But if we dig around a bit deeper, we can find estimates for about $500 million in revenues in 2018, and a variety of operating numbers that the firm used to post on its site. Let's start by building the brokerage business, which is the heart of the company.

We can find user numbers and wallet numbers here, helpfully scraped by Alistair Milne. Those start as low as 200,000 -- which by the way is not low at all -- and end around 35 million as currently disclosed. Total traded volume reaches $220 billion in 2020, and $150 billion in 2019. If we look at retail user assets, a $20 billion number is floating around in 2018 on Bloomberg. So let's take all this at face value, and derive average assets per user, which lands us at $800 in the average account.

That feels directionally right. Fintech apps have average accounts around a couple of hundred dollars, all the way up to a few dozen thousand for asset management. Since crypto is an alternatives asset class, I would expect a $10,000 portfolio to hold 5-10% or so in digital assets, which yields $750 per user. That's your average Millennial in 2017 right there. For prior years, we can assume a smaller average acount size, down to $100 per user. And for the outer years, let's keep it steady.

Why make the numbers lower earlier on? Because we think that the revenue for the company was only $16 million in 2016 based on reported figures. If this is wrong, then we would need to go back and correct average account sizes. In terms of user behavior, we can assume that people trade every two months, turning over about a third of their portfolio, with some spikes correlated to Bitcoin search volume. Coinbase spreads are somewhere between 3% and 1%, decreasing as the company grows. There is an additional fee generator in getting people from the banking system into the crypto account -- which can be 2% or more if users come in through a card, which we assume happens at a rate of 30%.

The net result of all the gymnastics is a brokerage revenue number of $700 million. Our math is simple and precisely wrong, but it should be directionally correct overall.

Secondary Businesses

Brokerage and exchange may be the bread and butter of the company, but there are other meaningful activities as well. Coinbase has the pro-trading business in GDAX, as well as an institutional trading arm called Coinbase Prime. We are going to hand wave this away into the retail numbers, because we think the overall reported assets are likely inclusive of the trading activity here.

However, there are still the custody and payment processing divisions.

For custody, there was about $1 billion in assets across 70 institutions in 2019. After the acquisition of Xapo, that number jumped to $7 billion and 120 investment funds. The total is impressive, but the economics for Xapo are somewhat challenging given that the service was free. Thus we apply a simple pricing assumption of 2% in 2018, 75 bps in 2019, and 25 bps in 2020. The real numbers are probably even more compressed, but why overcomplicate things! Let’s say that custody generates $20 million per year in fees.

On eCommerce, this was very much a shot in the dark. We know that there were about 16,000 Coinbase merchant customers in 2013, when the narrative was all about accepting Bitcoin for goods and services (remember Overstock, and then everything else about Overstock). Today, there are 8,000 merchants accepting the Coinbase processor, with a $200 million annual volume of goods sold. Stablecoins are the needed transformation to make merchants more likely to engage with crypto payments. That feels roughly right, with $25,000 per merchant in sales. We bring that number down to $1,000 in the early years, and add an exchange fee to get money out from crypto to fiat. All in, this is a $5 to 10 million revenue business, if run well.

So in total, how did we do? Looking at the model revenue, there is a ramp from $1 to $3, $6, $8, and $14 million in revenue. This is a good venture-backed company worth a Union Square ventures investment. But it’s not a dominant monopolist. Once we get to 2017, everything changes. Massive trading and customer acquisition happen at the end of 2017 and early 2018, and the user base increases 10x.

Revenue per user goes from a few dollars to $75.00, before falling into the teens thereafter. These metrics are in line with the neobanks, but with a larger footprint. Notably, the firm is also profitable — now printing nearly $300 million in cash per year. There is likely several hundred million of cash on the balance sheet.

Valuation and Takeaways

Asymmetric victories are asymmetric.

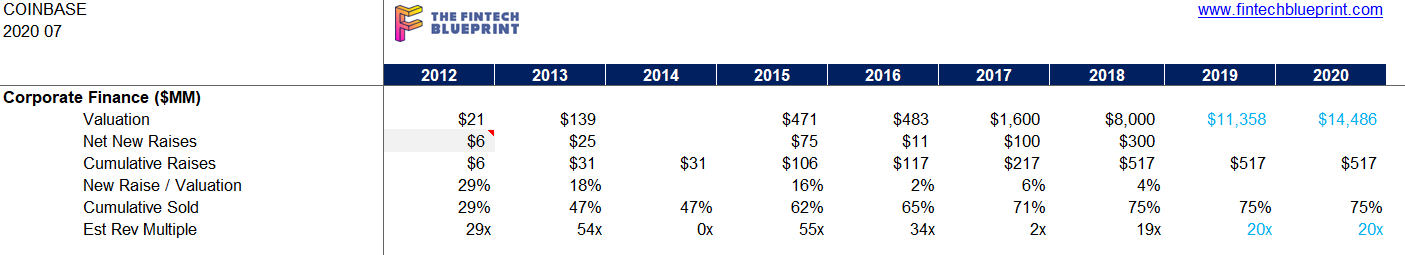

It’s not hard to find the financing history of Coinbase.

The latest round saw $300 million of money in at an $8 billion valuation. Before that, $100 million came in at $1.6 billion. Collectively, the company has sold 75% of its equity. That’s OK, because the 25% that remains could be work $3 billion to the team.

The valuation multiple varies between 10x and 50x, but assuming a cheap-ish 20x on revenues, Coinbase would be worth $15 billion today. Compared to Lemonade, this seems like a fair deal. You are getting 10x more in terms of the economics, with a reportedly healthy profit margin. Assuming those numbers are right of course.

Separately, this is a better bet than Bitmain, because it bets on human nature and not the adoption of a network. Coinbase does not need the Bitcoin network to print fees to sustain the company, nor does it need to fight a hardware war for mining rigs. It just needs to keep drawing people in to continue trading an emerging asset class that a young generation finds fascinating.

Our main takeaways, however, are about how important 2017 was for the company, and how it was likely impossible to predict that boom 3 or 4 years in. You might be building something for 5 years, and no stroke of luck lifts your company to the stratosphere. And then, all of a sudden, the skies open up, and a new industry awaits.

Nothing, nothing, and then everything.

The correlary to this is that if you spend years building things, do so cumulatively, not in adjacent manner. Those trading revenues are so strong because the users have added up into the many millions. This is the core of lifetime value, and why early customer acquisition can yield major dividends down the line.

So whether or not Coinbase does IPO, and whether or not our margin of error here is 5% or 50%, the playbook is clear. Build, and play the long game.

You can get more content like this in your Inbox for $3 per week -- the humble price of a delicious Fintech coffee. For exclusive analysis parsing over a dozen frontier technology developments every week, become a Blueprint member below.

Hi Lex,

I have been reviewing your model about Coinbase’s valuation. It's very interesting. And I have a question about the premise on Brokerage onramp fee (line 40).

You say: There is an additional fee generator in getting people from the banking system into the crypto account -- which can be 2% or more if users come in through a card, which we assume happens at a rate of 30%.

But in model, line 40, you take a 10% of yearly delta users (line 35). So, I understand that, in the calculation of the “total onramp fee ($MM)” you use:

Line 40 … =(F35+F37)*F26*F38/1000000*F39

Instead of:

=(F37)*F26*F38/1000000*F39

If we use (F3+F37), change the data about the delta and the number of users per year. Then the model adds 32.100 users additional to 2013, so the number of users in 2013 change from 521.000 to 553.100, and the same variation in the next years.

The next data (“Churn %”, line 36, and “% Using on ramp”, line 39), could be adjusted to obtain the result in revenue in 2017, near to $1.000 MM to validate the supposes.

Would you give me some piece of advice, or if I am wrong.

Thank you