Hi Fintech Architects,

Welcome back to our podcast series! For those that want to subscribe in your app of choice, you can now find us at Apple, Spotify, or on RSS.

In this conversation, we chat with Zuben Mathews - CEO and Co-founder of Brigit. He started his career at Deutsche Bank, where, over the course of 11 years, he created and led a principal investment and banking group, the Strategic Partnership Group, and focused mostly on financial technology and software companies. During this time, Zuben led equity, debt, and M&A transactions worth more than $55 billion.

He became the Managing Director of Mergers & Acquisitions at Infosys. Zuben received his BA in Economics from the University of Chicago.

Topics: Fintech, neobank, overdraft, cash advance, subscription, financial wellbeing, PSD2, regulation

Tags: Brigit, Deutsche Bank, Plaid, Chime, Revolut, Monzo, Yodlee, Synapse, Coastal Community Bank

In Partnership

We are supporting The APAC Family Office & VC Online Conference. Join 500+ family offices, VCs, venture studios, founders & angels at the APAC Family Office & VC Online Conference on Sept 20th at 3 PM Singapore for 3 hours (join any time). It’s a virtual event on Zoom.

Some of the topics to be covered:

VC Trends in APAC in 2024

How to fundraise from Family Offices?

How AI is changing venture building

Register for free or buy a paid ticket: 👉 https://inniches.com/apac

Timestamps

1’36: From Deutsche Bank to Brigit: Zuben Mathews' Journey in Finance and Entrepreneurship

5’03: Bridging Silos at Deutsche Bank: Detailing Strategic Vendor Partnerships and Fintech Insights

9’06: From Startup Struggles to Success: Building Brigit and Navigating the Challenges of Entrepreneurship

15’41: Solving America's Deepest Financial Pain Point: The Vision Behind Brigit's Differentiation in a Crowded Fintech Market

21’07: Leveraging Cashflow Data to Outperform Banks: How Brigit Built a Product to Tackle Overdraft Fees and Expand Financial Access

24’47: Beyond Overdraft Protection: How Brigit Uses Cashflow Data to Reduce Financial Stress and Drive User Engagement

29’01: Balancing Affordability and Financial Health: How Brigit's Subscription Model Empowers Users While Lowering Costs

33’25: Challenges of Data Access in US Fintech: Navigating Bank Transactional Data and the Push for Open APIs

40’36: Navigating US Banking Rails: The Role of Regulation, Innovation, and Customer-Centric Solutions in Fintech

45’24: The channels used to connect with Zuben & learn more about Brigit

Illustrated Transcript

Lex Sokolin:

Hi everybody and welcome to today's conversation. I'm super excited to have with us today Zuben Mathews, who is the CEO of Brigit. Brigit is one of the largest consumer financial apps in the United States and has achieved some really profound milestones. I'm very excited to learn more about Brigit, its journey, and Zuben's background. With that, welcome to the podcast.

Zuben Mathews:

Thank you, Lex. It's an absolute pleasure talking to you, man. As I pointed out earlier, talking to a prominent voice in fintech is something that's an absolute pleasure. So, thank you for your time.

Lex Sokolin:

You're very kind. It's one of the fun things I get to do is talk to awesome entrepreneurs and CEOs. So maybe before we even start with the Brigit story, tell us about what brought you into finance and what were some of your definitional experiences in the industry?

Zuben Mathews:

So, quite frankly, a lot of my life relates to what's happened to get me to Brigit. So, I actually came to the United States, I'm dating myself, almost 20 years ago, where I was fortunate to get a full tuition scholarship in Chicago, at the University of Chicago.

One of the first things I wanted to do there was actually study economics, and the natural progression from that was trying to get a job in finance. So that's what led me to a job in technology investment banking. So, the experience of that helped me understand fintech a little bit more because we were doing fintech deals, as well as being able to analyze what the banking world really looked like.

So that was the first foray for me to actually understand, hey, as an investment banking analyst, how do people look at public companies, how do people analyze companies, and just actually get my foothold in the world of banking and understand how banks actually work. All of those things, whether it was me joining college to study economics and getting that first job, laid the pillars of what is Brigit today.

Lex Sokolin:

So you joined Deutsche in banking. Once you got there and you got the lay of the land and understood how the machine worked and how things operated. What was interesting to you? Because you spent quite a bit of time in an investment bank.

Zuben Mathews:

Yeah, no, I spent a little over a decade. I think there were a few things. First was just the sheer rigor of how much work you had to do to get something done. So, there is the actual execution that your seniors would tell you, your MDs, analyst, associates, whoever it is, on how to actually think of something and actually produce it.

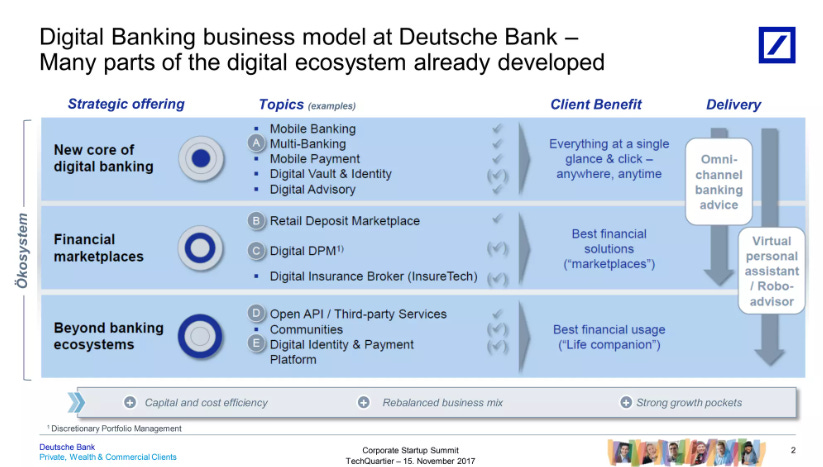

Then from that, one of the reasons I stayed was I actually came up with an idea to build a small team, a P&L-led team, within the bank that would actually leverage the bank's data, specifically how much money the bank was spending, as well as what partnerships it already had to help generate investment banking revenue.

So, it was kind of a mini startup. It was a mini startup with full P&L responsibility that actually was structured in a large organization. So, the spirit of entrepreneurship was alive, quite frankly, even when I was at Deutsche, and that's one of the main reasons why I stayed for so long.

The experience is there. You learn a lot about not just how clients perceive companies, not just the fact how investors look at certain aspects of companies, whether it's the financials, the overall ability to build a large company, but as much as all of that stuff, you mentioned how the industry works, but, quite frankly, also how the sausage is made.

But you start to learn a lot about the operations of a bank, and no matter what bank you're in, you start to understand how archaic certain systems are. It doesn't matter if you're a Goldman Sachs, a Deutsche Bank, et cetera, these are large organizations that work fundamentally slowly and have vested interests, not to mention the fact that their tech tends to be, in many cases, 30 years old.

There's a lot of learning that you end up getting, fortunately, in a period of 10 years, and I was also fortunate to have a set of great bosses who helped me understand different aspects of the bank.

Lex Sokolin:

That's super interesting, because it is extremely difficult to start a new business inside a large institution. So, hats off for that. How did it work? What kind of data were you able to pull? Then do you have some examples of deals that you did as a result of that?

Zuben Mathews:

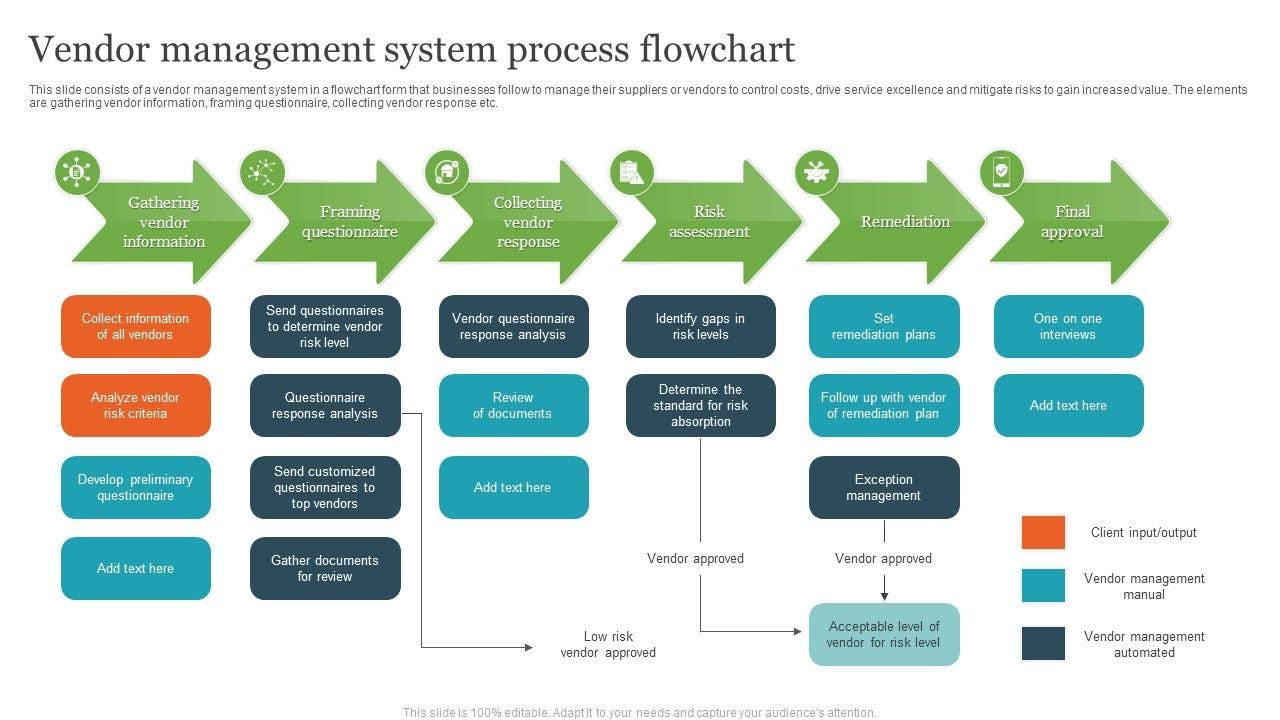

Yeah, absolutely. So, the idea was, look, Deutsche Bank at that point in time was spending $3, $3.5 billion on partners and vendors. The question that ended up being was like there's an entire selection process on why, in some cases ... I don't want to say arbitrary, but semi-arbitrary on why a bank selects one vendor over the other. But at no point in time there is the right hand speaking to the left hand and saying, "Hey, these are our set of clients that we are focused on trying to win business from or potentially invest in. Here's a set of companies that we're looking at buying certain things. How do you bridge the gap and look at these decisions in a holistic point of view?"

So being able to make sure the procurement team is aware that there is a set of clients that they should at least consider as part of the procurement decision. At no point in time should the procurement team or the tech team make a decision solely based on the client relationship, but just make sure you factor in all of those things.

So, both sides of the fence, making sure the technology bankers or the fintech bankers, or any aspect of the investment banking team, understood how much money was being spent and by whom, and vice versa, obviously within control by compliance. So being able to bridge how much money we're earning relative to the relationships, relative to how much money the organization might be spending with those particular vendors or partners was something that we were bridging the gap to, all, and this is the hardest part, in a compliant manner.

So you make holistic decisions on behalf of what would be a hundred thousand-people shop versus doing things in a silo. That was part of the job.

Lex Sokolin:

What better fintech signal than a company like Deutsche Bank using a technology vendor within its capital markets business? It can go both ways where the vendor to the bank is probably a good company and a good client if you can do corporate finance for it, and vice versa. It gives you a real understanding of the industry by seeing the landscape of the companies that are serving the banks.

Zuben Mathews:

Yup, you've got this right. You asked for an example, and I'll actually give you one. There's a company, this takes me back, called Copal Partners. The founder now runs OakNorth in the UK, obviously a pretty large, very successful fintech. We realized that at Deutsche Bank, we were going to use them for analyst outsourcing pretty early on. The quality of the work they were producing was, quite frankly, fabulous. The fact that they were based in India as well, we could actually do a follow the sun approach, be it from the United States or the UK, which is most of where the investor banking analysts and associates were.

So, I actually led a position. We ended up investing and owning, what, 10% of the company. About five years later, because they got massive traction, the quality of the service was fantastic, there was a win-win on both parts, and they ended up selling to Moody's. We ended up getting about a 25X return.

So, here's an example where as long as the left-hand side, the right-hand side know what people are doing in a compliant manner, these ... As you pointed out, fabulous signals for what would potentially be a multi-hundred million outcome in this example for Copal Partners. There are quite a few other examples like that, not just on the investment banking side to originate fees but including investments.

Lex Sokolin:

I think at this point it's kosher to share this detail, but quite a few years back, I was talking with Point72 and their ventures team focused on fintech, since Point72 has blown up their fintech team, I think, in favor of chasing generative AI. But the fintech team was looking for investments by going to all of the banks in their network to the corporate finance teams, but then also to the tech selection layer of the organization and trying to figure out who do the banks work with. That was their sourcing strategy was go to where the traction is, and we know where all the traction is because we know all the people in these companies.

Zuben Mathews:

Yeah, there are quite a few who do that. I think one of the people who used to run the fintech practice there worked at FTV Capital, which is part of their core thesis as well, is understand what the banks are doing, get as deep as possible, and find early signals.

Lex Sokolin:

So I imagine that building a new business within a company like Deutsche, there's a lot of influence, there's a lot of persuasion. Of course you do a business case. It's going to be very rigorous, but in many ways it's a political process, correct me if I'm wrong. With a startup, you are just in the wilderness digging for water. Can you talk about Brigit and the early days of trying to pull that together or trying to pull that business together, and what was that experience like?

Zuben Mathews:

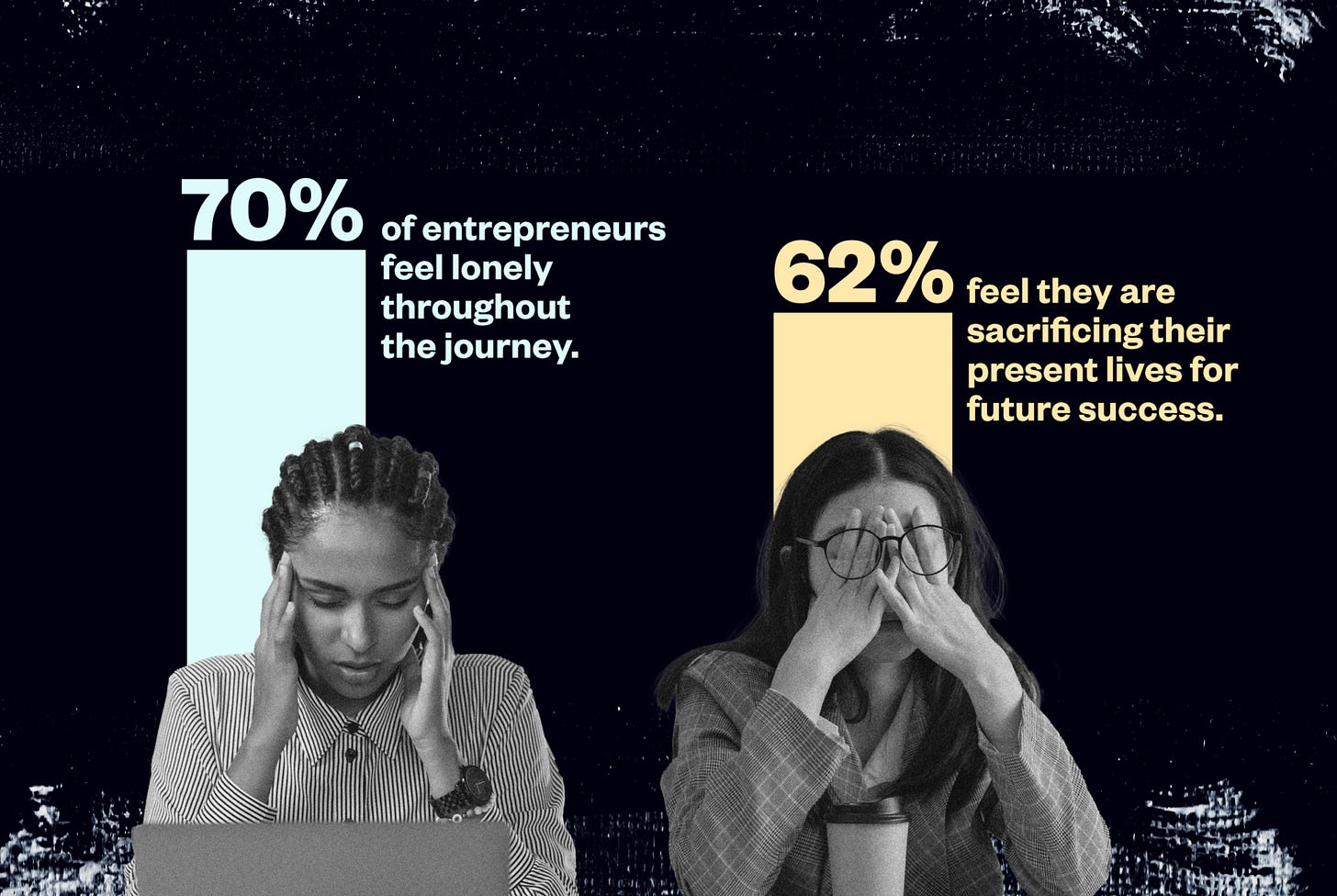

Well, if we speak to any founder, which obviously, Lex, you've spoken to so many over the last several years, it's a very lonely and probably the hardest thing any of the founders have done, especially if they're trying to build it from scratch. So, there were a lot of 4:00 AMs in the morning, waking up with literally a blank piece of paper and saying, "Hey, how do I solve the deepest problem that is close to me and is also personal to me?"

So that is something that's very, very lonely. I think one of the things I realized early on is I wanted somebody smarter at the same time with a complementary set of skillsets to come join and help me start what my vision was.

It took me almost nine months to find the right person. I think when you start to think about how hard it is to not just come up with the idea to start to figure out, try to get some traction, in my case get that co-founder who has turned out to be an absolutely amazing decision in my life and I got very lucky, building those components, coming up with a business case, and then finally recruiting a team, none of those things ... Not to mention getting funding, especially seven years ago, whatever it was, all of those things are lonely, painful places.

But the beautiful thing about that is if you're mission-oriented and you are able to attract the right talent, the end result, quite frankly, if we ended up succeeding or not, would be worthwhile. So, I don't know how best to answer that question except that it is a very, very tough, lonely journey. But every time you have some success ... And don't get me wrong, you'll get some failure to match it ... if you can see yourself move forward in 1,000, 10,000, 1 million small steps and you can take pleasure from that or accomplishment from that, that is the only way I see any startup succeeding.

Lex Sokolin:

Through my entrepreneurial experience, I would describe it as life by a thousand cuts rather than death by a thousand cuts. So, if you're not going through that constant painful failure in everything you're doing with the occasional huge breakthrough, you're not making any progress because you're just standing still.

Zuben Mathews:

I mean enjoy the journey. That's what people say.

Lex Sokolin:

Maybe we'll do a spoiler here and just shortcut to now, what is Brigit and what is it today? Can you talk about the scale of the company, anything you can say about the number of users, employees, revenues? Frame for us what Brigit has become and then we'll unpack how you got there.

Zuben Mathews:

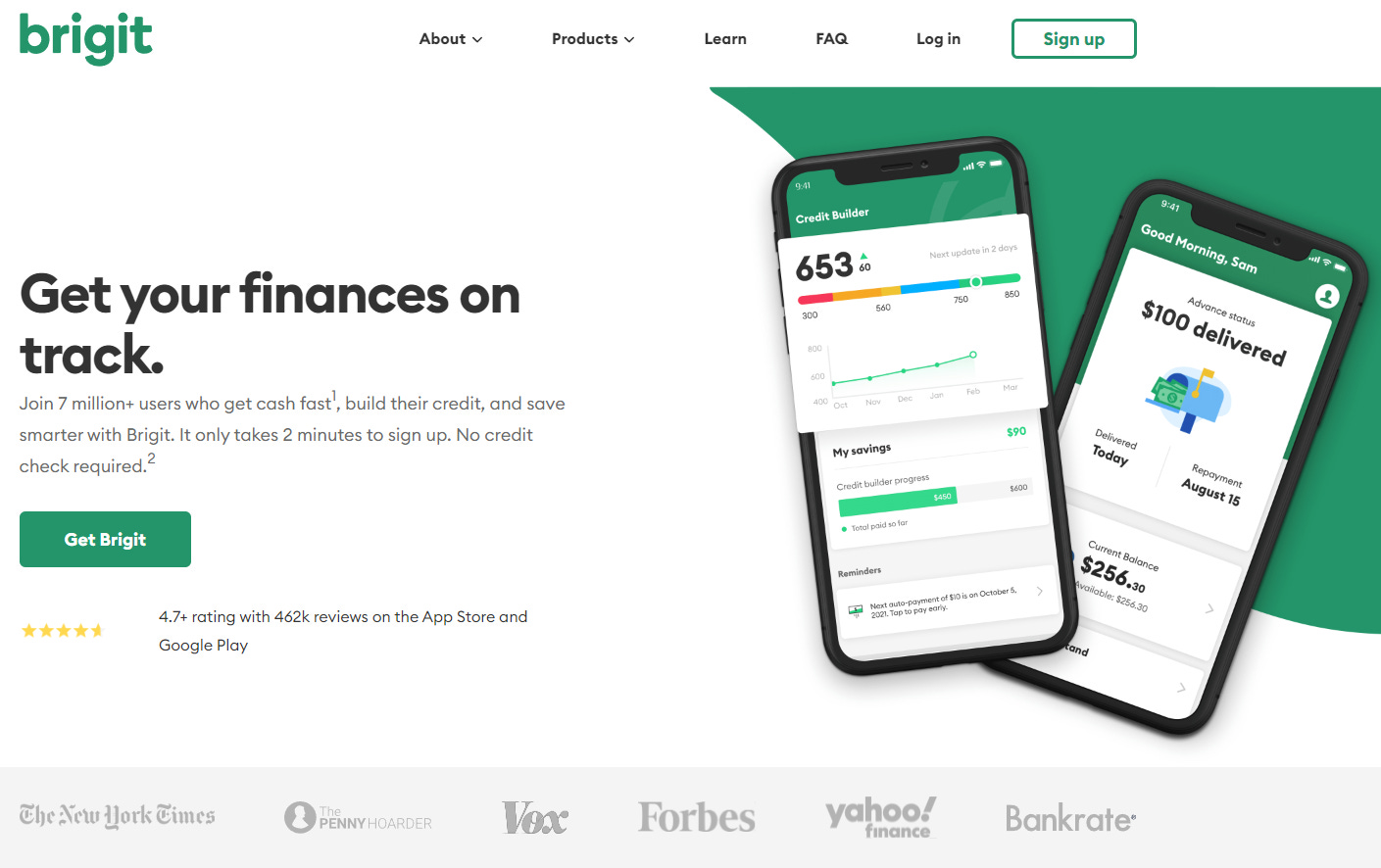

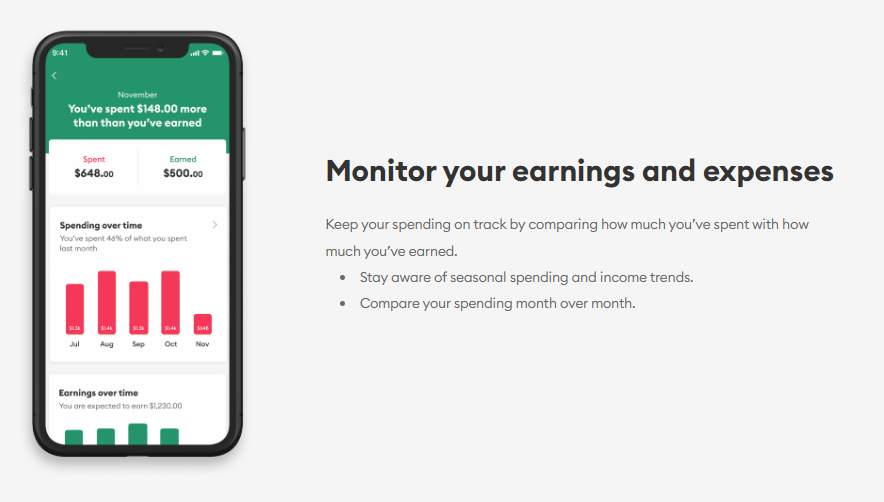

Sure. So, the wonderful empty piece of paper that I discussed that I was working on at 4:00 AM in the morning today is the most downloaded financial health app in the United States. We offer a suite of holistic financial products that include budgeting, financial insights, ability to get access to paychecks, as well as being able to build your credit score by savings. That entire package is what we offer through a subscription.

The good news is, again, from being an individual waking up at 4:00 AM, today we have over a hundred million in revenue. We are profitable and have been for the last couple of years. In terms of team size, we're only 90. So, if you think about the core technology that we've built and everything that we do, and I'd love to talk more about this, is based on cashflow information.

So, at the end of the day, we are very much a data company that leverages people's bank account information, so their income, their voluntary income, historical spending pattern, to leverage and serve these individuals.

We have a million paying subscribers today as well, and one of the things that I'm most proud of from a technology perspective, because guess what, I didn't actually have to build that, is the fact that we were able to serve these million people and well over a hundred million in revenue with just 90 team members. So that should give you a sense of how "effective" the technology is.

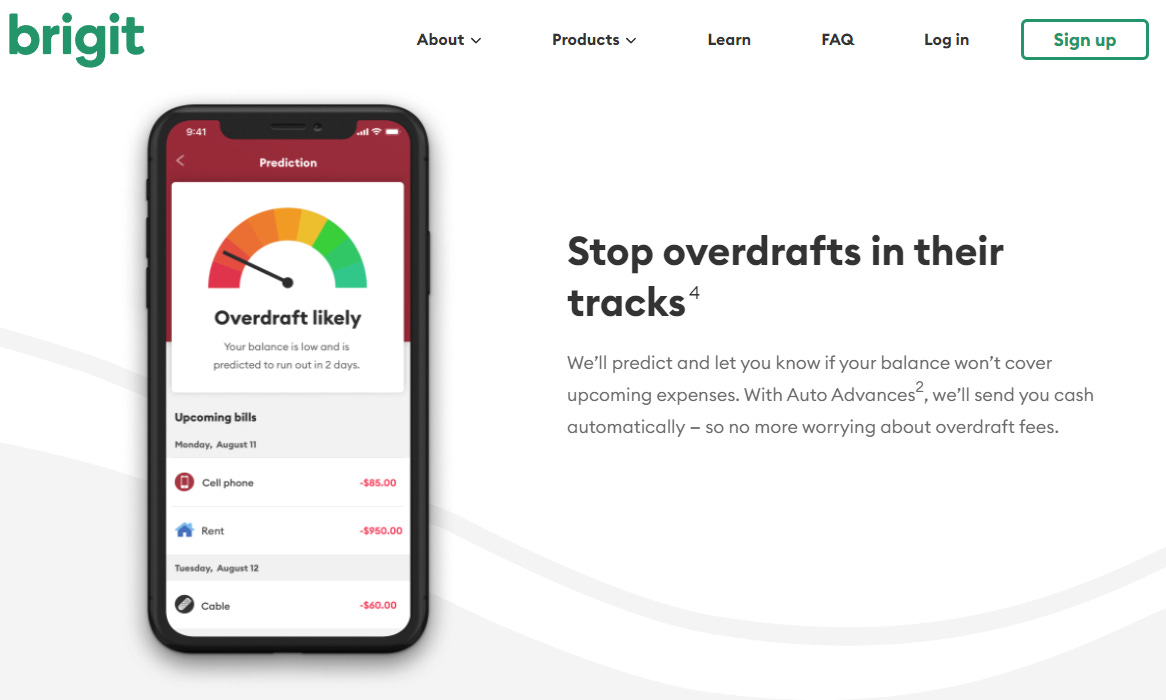

The other aspect, if it's okay for me to talk about, is the reason why we started this business in the first place, which is to have true social impact. At the end of last year, we had actually helped people save over a billion dollars in fees by avoiding overdrafts or late payment fees, and 94%, 94% of our users feel less financially stressed because we use our product. That to me is a step of success, because that is the single most important reason why we started the company in the first place.

Lex Sokolin:

Those are amazing numbers. Hats off. Let me push a little bit, however, on what must have been that founding moment. So, you started the company 2017. By that point, we've had personal financial management apps since 2007 with mint.com, rest in peace. There was at least 10 years of trying to track and budget online and things of that nature.

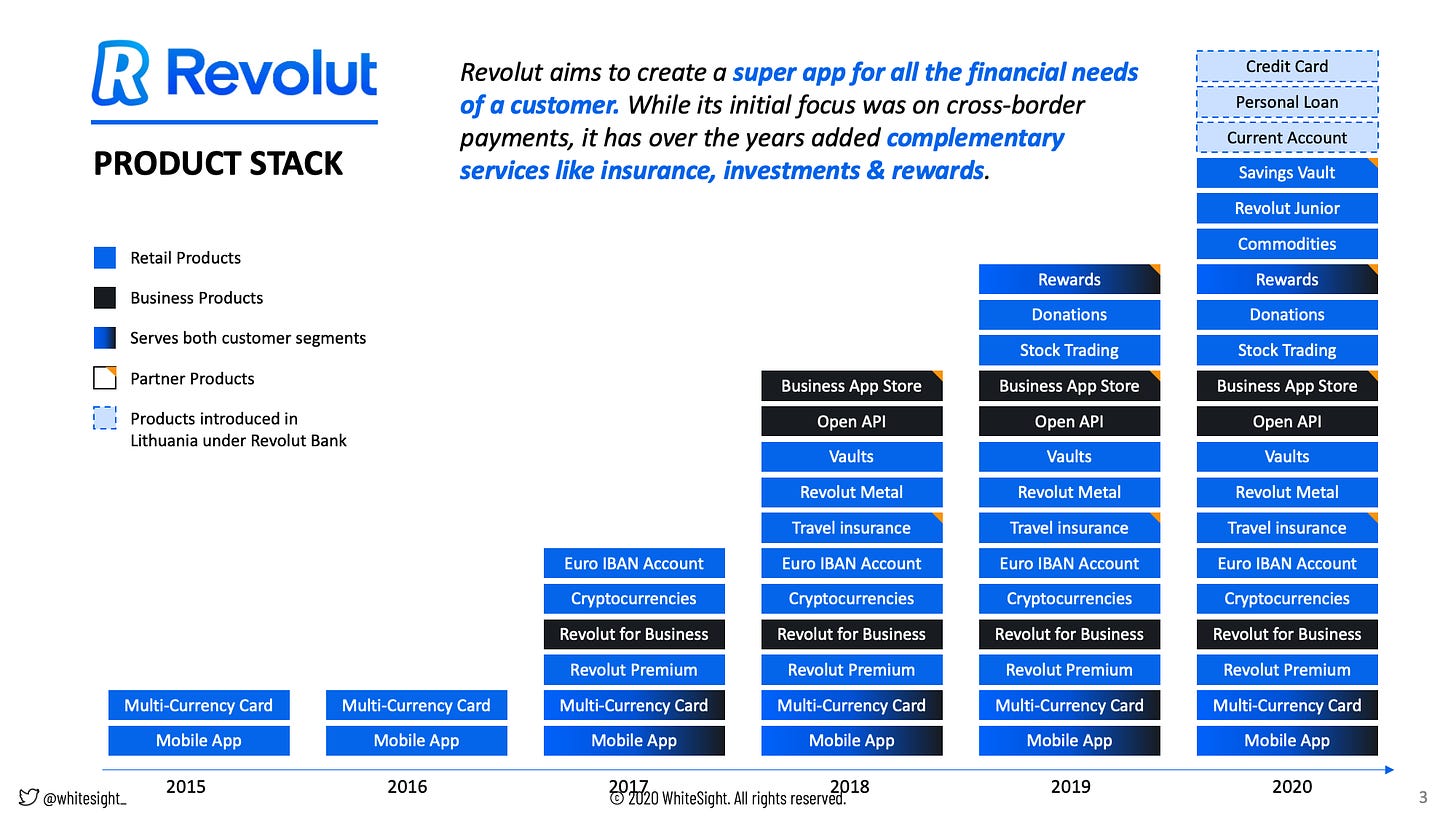

In Europe, in the UK, I think around 2014 is when we had the first fintech and neobank wave. I know that Brigit's not a neobank, but in terms of how people think about the buckets of financial experience, you had the starts of Revolut and Monzo, and then, of course, in the US, you started getting companies like Chime popping up. It wasn't a blue ocean. It was a problem that lots of people were attacking.

What was your vision that sliced through that and said, "We've got a differentiated way to get there"? Maybe this is a way of asking about the product within the context of where the industry was. How did you look at all of this fintech stuff around and decide where to enter the market for yourself?

Zuben Mathews:

Sure. So, there's a couple of things. I mean you brought up Monzo, Revolut, and Chime, some of the greatest companies out there. But, again, as a student of fintech, they're all trying to solve, at that point in time, very specific problems. Revolut obviously, being in the UK around that point in time, was solving the situation of an 18-year-old or a 19-year-old taking a leap year or gap year and going to Europe and making sure that FX was more transparent.

Monzo was building what would be a formal bank in the UK with a much better experience and brand, and Chime initially was the second chance bank account at that point in time for people. All doing very specific things and starting to gain some great momentum.

For us, keeping aside what was out there, we weren't really looking at the competition per se or what was happening in fintech, obviously learning, including from all of those great companies that you've mentioned. But for us, it really came down to what was the deepest pain point that we could solve, specifically here in the United States because we're based here.

It went back to one of the questions you asked earlier, is I came here about 20 years ago, here in the United States, as an immigrant. I was fortunate enough to get a full tuition scholarship. Despite of me having two part-time jobs and my mother sending me money from India, I ended up being almost always short because my expenses would be due now or the beginning of the month, and I'd only get paid, or remittances would only come in a few weeks later.

Let me be clear, I was living within my means. My expenses were less than my overall income, but it was a fundamental timing mismatch. I ended up spending a fortune on overdraft fees simply because I was too ashamed, or proud actually, to borrow from friends and family because, again, I was living within my means.

The first year I spent over $1,000 on overdraft fees, and I'm telling you this, Lex, I fundamentally remember every single time I look at my bank account hoping that I hadn't gone under. There were enough nights that I would spend downstairs near the vending machine eating Snickers bars just to avoid that level of stress.

Now here's the unbelievable part of it. Fast forward, give or take, 20 years later, the United States is still the single wealthiest country in the world, yet three-fourths of our populations, three-fourths, live paycheck-to-paycheck. It was fundamentally clear to me that that Zuben who had suffered 20 years ago and now with this experience in finance could solve a way to make sure that people don't have to overdraft, don't have to borrow from friends and family, or use payday loans to bridge that gap that I was suffering from.

The amazing part of it was, in 20 years, there weren't transparent solutions to solve for that. That is the reason why we focused on what we would define as the deepest pain point for the largest segment in the United States, which is making sure that less people live paycheck-to-paycheck and less people have to stress about their finances.

That is why the initial product that we built, again using only cashflow information, not FICO, because, again, FICO would be wonderful for certain aspects but not for most of America for this use case. So, understanding all that information that changes in real time, cashflow information, bank transaction, open banking, call it whatever you want, to deliver money when people needed it the most. Either they could ask for it or we built algorithms that would pre-fund money if they so wanted it, so they never even have to think about overdrafting.

That was our first core product. It's not the product we necessarily wanted to build, but it was a product that we realized was the deepest pain point that people needed. So that is why we went in that direction. Of course, Revolut, Monzo, Chime, all amazing companies, but I will also point out that they were solving different, also very important pain points. But we approached it as a user problem, not what was out there in the market. So that's how we ended up landing to where we were, at least on our initial product.

Lex Sokolin:

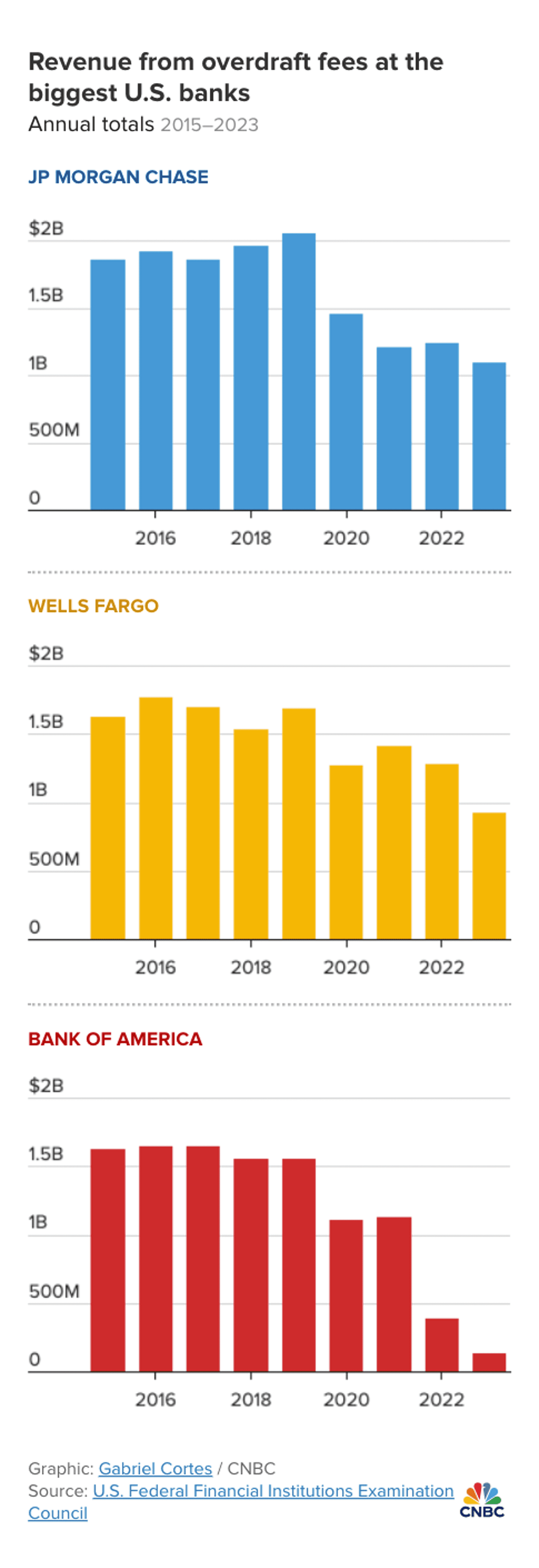

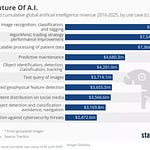

That's very powerful stuff. Thank you for sharing that. A number of companies found hooks into the industries being really specific and in a way niche, going after these revenue pools that large banks have left alone for decades, whether it's the effect spread or whether it's the wealth management fees of 150 basis points down to 25 basis points, or whether it's the inability to use data and underwrite customers, and instead charging them pretty exorbitant overdraft fees or ridiculous interest rates. It's like its money lying on the ground, and so you can build that initial wedge to go after that revenue pool.

Can you talk about, from a product perspective, a bit more how you were able to get that data advantage, and then how were you able to do something that the large banks weren't able to do in terms of getting your users to avoid being in that overdraft situation? Then maybe what were the main product levers of the business as you continue to grow and expand?

Zuben Mathews:

Sure. There's a lot to unpack there. Maybe I'll just talk about the banks because they're not necessarily ... I mean banks are important from a partnership perspective, but also, they have their own vested interest.

You brought up the question of why banks couldn't use that specific level of data. Look, the reality is banks, especially with overdraft fees, have been making $30 billion in NIBIT. I mean Chase still makes about 2 billion in NIBIT from overdraft fees. And guess what? It's not like people like you and me who end up paying those fees, they comp the fees for people like us. Unfortunately, for the median American is where they end up charging all those fees.

So, historically, they haven't had a vested interest to take away that massive fee pool or use that data for underwriting, at least in this use case. The reason why we were able to be competitive specifically on cashflow data was for a number of reasons. We were solely focused on cashflow as we are today. That is the single data point that we use to build our products, and it's not just for risk management. I'll give you some examples there.

But we were fortunate enough, from some relationships, that I had that even before we formally started our company, we got our hands on a few billion cashflow transactions so we could back test. We had this vision of saying, "Hey, let's use cashflow information to solve this massive pain point." Sounds great and we know theoretically it works, but let's actually get the data, because nothing is as good as actual data, to at least try to start to back test.

The next thing that I pointed out earlier is you needed a great team. Fortunately ... And the reason why it took such a while for me to get my co-founder was, I was looking for someone, again, in 2017 in the United States who had experience in cashflow data. It didn't really exist.

My co-founder Hamel used to work at Palantir and Two Sigma, and he had actually worked on cashflow solutions in Brazil as part of Palantir when he was working there. We were very fortunate to get a couple of other team members who had worked with him a couple of years prior in Palantir. So, the combination of having this vision with the piece of data that I mentioned earlier, with the right team got us this fundamental advantage to get to where we are.

Look, the reality is there's no silver bullet. We have built 50 models over the last five years. We continue to iterate really, really fast, and that's led us to today for the core product, which is our instant cash product. We have 2X'ed our approval rates of traditional lenders while having about 2% loss rates. That is fundamentally a testament of the ability to get the right data and be fundamentally focused with this amazing team that we're lucky to work with on a daily basis to focus on providing impact. It's no silver bullet. It is fundamental, consistent improvement on a daily, weekly, honestly, hour-by-hour basis.

Lex Sokolin:

So if I'm understanding right, the primary lever is the ability to underwrite better. It all boils down to being able to see risk better and then to be able to offer an advance or a credit builder product, which then gets the consumer out of the trap, the overdraft trap, that they're in because they have cash up front. You're able to use cashflow information, meaning when you would expect the paycheck to come in and what the expenses are, to better solve using the models that you're talking about, to better solve the equation of whether you can trust to give this person money or not. Is that right?

Zuben Mathews:

That is one of the aspects. As I pointed out, there are a couple of other use cases. The other one is, at the end of the day, our core focus is to help reduce people's financial stress from a qualitative perspective. From a quantitative perspective, it's making sure we can help save them money.

Our initial use case is exactly what you talked about, which is the ability to avoid overdrafts. One of the other things that we do is use algorithms to predict when people need money. Again, if they have that opted in, we pre-fund their account so they don't even have to stress about it.

That actually helped us get to our first 20 million in ARR very quickly. In fact, much faster than even the likes of Chime, Revolut, and Monzo. In fact, we got to the 50 million plus in a faster and more efficient way.

But that was just the start. The ability to leverage cashflow information to give you financial insights well beyond budgeting is something that we are very proud of. Let me literally give you an example from last week.

I'm here in New York. My Con Edison bill came and there was an autopay. The system, Brigit system, realized that "Hey, Zuben just paid 35% more than he had paid last month. Let me let Zuben know that." So, the system sent a message saying, "Hey, Zuben. Your Con Edison bill is paid. It's quite a bit more than what you've paid last month. By the way, obviously it's the summer here in New York. Here's a piece of content that will give you some ideas how to self-help to help reduce your bill for the next month."

That's some of the type of examples that we're using, again, cashflow information that is delivered in real time to provide users feedback to try to get them the right message at the right time, to help them reduce their fees. Similarly, as the way our credit builder works is that we help people build their credit score and save at the same time. If we see changes in the cash flow information and the credit score being built, we say, "Hey, we know you have this car insurance. Now with a higher credit score, here's a partner that we can send you. We'll be able to reduce your insurance bill even more."

So, the reality is the product suite as it exists today, with the core technology and data of cashflow, ends up working in harmony to help people get to a better financial state. So, it's not just about cashflow, not just about instant cash advances, it is the harmony of how the products play well together. That's one of the reasons why our engagement from a DAU/MAU standpoint is actually higher than even LinkedIn. Our number of sessions every month is about seven sessions.

So those are some of the reasons why we're super excited on how ... Initially we used instant cash or the overdraft avoidance as the deeper solution. But look, the reality is we want people to borrow less. We want people to save more, build that credit score, because at the end of the day, because we're a subscription-based product, as people graduate and get better in their financials, our financials also improve because our costs are lower.

Lex Sokolin:

I want to talk about the infrastructure, the data, and the banking services in a second. But before that, I'd like to pause on the economic model because you brought up subscriptions. I'd love to understand that a little bit better in terms of how much you're charging users, because you're saying there's a million people who are subscribed and you're generating over a hundred million in revenue as a result of that. Then on the other side, you've brought up how difficult it is for this demographic to live paycheck-to-paycheck, and to miss even a week of timing in their budgeting can be really detrimental.

Then, of course, any sort of underwriting is transactional. All the financial institutions are incentivized to create more borrowing and to create more underwriting, because at end of the day, they make money in a failure state.

Can you talk about the subscription model? How do your users afford it? How does it fit into their budget? Then how does the subscription model also overlay with the underlying financial activity that the app powers?

Zuben Mathews:

Sure. So, in terms of how ... Look, at the end of the day, it comes down to how much value you provide at the end customer. We talked about the engagement numbers a little bit earlier. But if you're helping users save $400 at this point in time on an annual basis while charging approximately ... We have two pricing plans, but the blended rate, depending on the plan, is about $10 a month. That's a significant amount of value in order to save people a lot of money and a set of financial stress.

The reality is if we weren't providing significant value, our retention rates would be through the roof. We wouldn't be able to be profitable, and as well as our engagement numbers wouldn't be that strong.

The reason why we chose a subscription model, and we had initially looked at some other models, was actually advice from one of our advisors who's at the financial health network and also did a lot of research at the CFPB on overdrafts. In fact, if you Google Corey Stone, you'll see he's the person who helped initiate a significant amount of overdraft research at the CFPB.

His thesis was very simple and clear, provide these users the best value you possibly can in the most transparent financial model you possibly can. For us, the most transparent model clearly was a subscription because there's no gotcha fees at the end of it. There's no tips, there's no APR, there's no late payment fees. People know fundamentally, clearly what they're signing up for and when they have to pay for it.

By the way, we don't charge people upfront. We charge people at the end of the 30-day period, just to make sure they can obviously afford it. There are thousands of people who we don't actually even take subscriptions from if we think they're not going to be able to pay it for that particular month. That is how the algorithms are set up.

Now the reason why we went with this from also an impact point of view is, as you pointed out, if you are a traditional lender ... And remember, we are a financial health app with a suite of tools well beyond the instant cash product that we talked about. If you're a bank or a lender or, quite frankly, even our competition, they want you to borrow more. They want you to borrow more and they want you to borrow more often because that's how they're going to improve their overall revenue as well as their profitability.

From our standpoint, we're looking for long-term value for the end customer, long-term value for us by providing short-term value and long-term value for the end customer. Let me explain. As people, a lot of our users do come in for short-term liquidity, as we talked about, but we want them to borrow less because as they borrow less, our costs go down. As they move from borrowing to budgeting, they're graduating away from needing a product like instant cash or borrowing in the first place.

As they budget a little bit more effectively, they have more time and thought ... They have time available to use other features like our credit building tools. By leveraging our credit building tool, they're not only improving their credit score, they're actually saving money in our account. Also, the ability of improving a credit score has a fundamental overall effect where they're able, as I said before, to reduce their insurance rates, to reduce any other cost of the personal loans they might have, and it's getting them to a better state.

Hence, the statement that I made. As our users graduate and improve their financial lives, our costs actually reduce and our financials graduate with them. It is the polar opposite of being a bank making money the more you overdraft, or even our competition which is saying, "Hey, take more money, take more money, take more money, and take it more often," because they're making tips and other fees every time somebody borrows.

Lex Sokolin:

The beauty of the subscription model, end of the day, is people know what they're paying. Just the transparency of that is really important, because across the full footprint of the audience, different people will have a different amount of value that they get from the service. But if they can at least make a clear decision about this is how much value I'm getting from access to these tools and this is how it's helped me over time versus the fixed cost, that's a fair decision that they can make. I'm glad to see fintech bringing that model into the space, creating the transparency that people can make an informed choice.

Zuben Mathews:

No, I appreciate that. As you can imagine, it's easier to have even more growth if you don't have a $10 sticker from a subscription upfront when people think everything is free, but you're also providing fundamental transparency. So then at the end of the month, when they choose to cancel or not, from our point of view, if we keep adding value to our customers and they clearly perceive the value that we're providing them, they'll stick around, which is what's, fortunately, been the case for us.

Lex Sokolin:

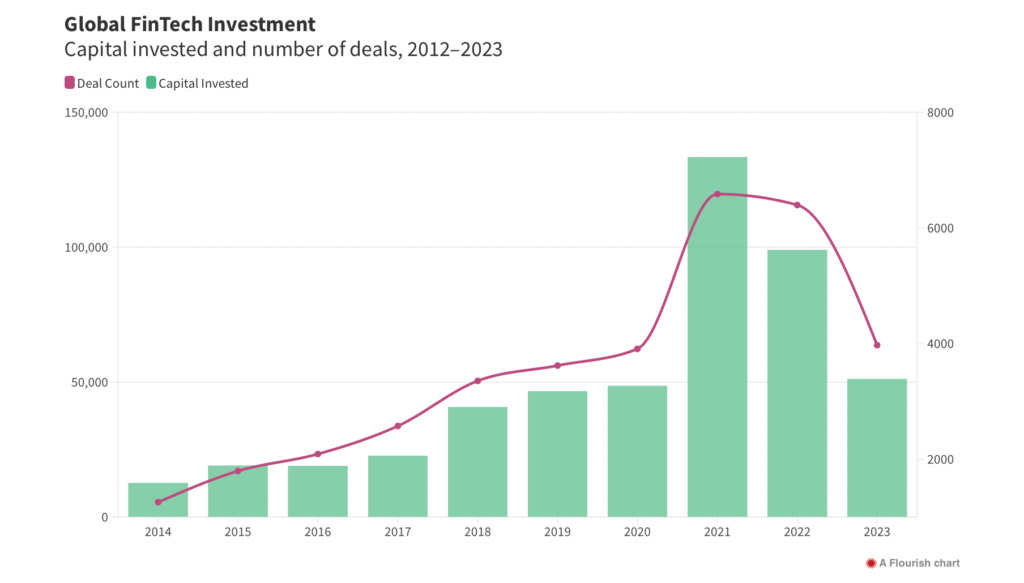

One of the biggest sources of damage for the fintech industry and capital markets and the ability of companies to go IPO has been venture investors treating lending revenue as if it were a SaaS revenue. There's so many fintech companies that are really good at giving away free money and then generating lending revenues, and the venture industry is not particularly skilled in seeing the fact that all that upfront revenue actually comes with huge credit risk down the line, and then you end up getting all that stuff marked up at venture revenues, taking those companies public, and having a bad experience. I feel like that's one of the key issues that should be fixed for companies in our space to just have a good experience going public.

Zuben Mathews:

I think there's a lot of learnings, as it should be, from 2022 for the entire venture community, for fintechs in general. Hopefully there's more regulation as well and just better companies coming out because of the limited amount of funding available today.

Lex Sokolin:

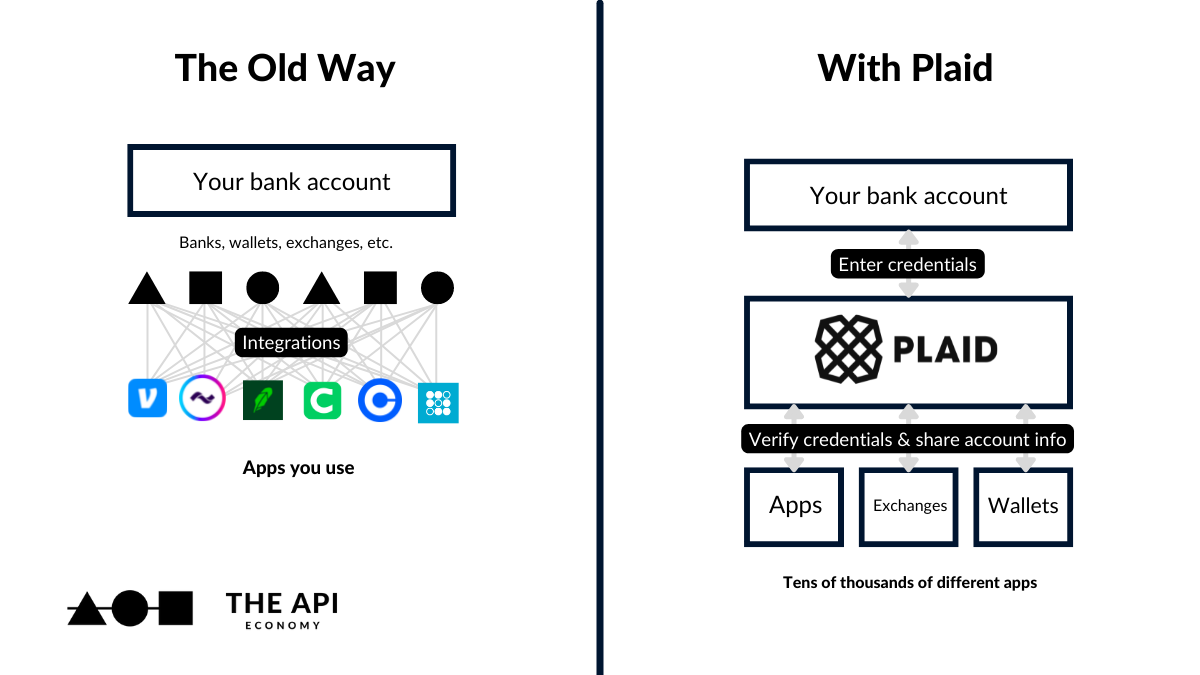

So let's try to bottom out a little bit of that infrastructure discussion. There are two things I want to touch on. The first is you've brought up having access to cashflow data. So, one question is where do you get the data? What's the engine that flows that through? In some way, I guess, is that sufficient? The context for is that sufficient is that if you look across the world and different geographies and regulatory regimes, there are different lenses as to who the financial data belongs to and how open it should be.

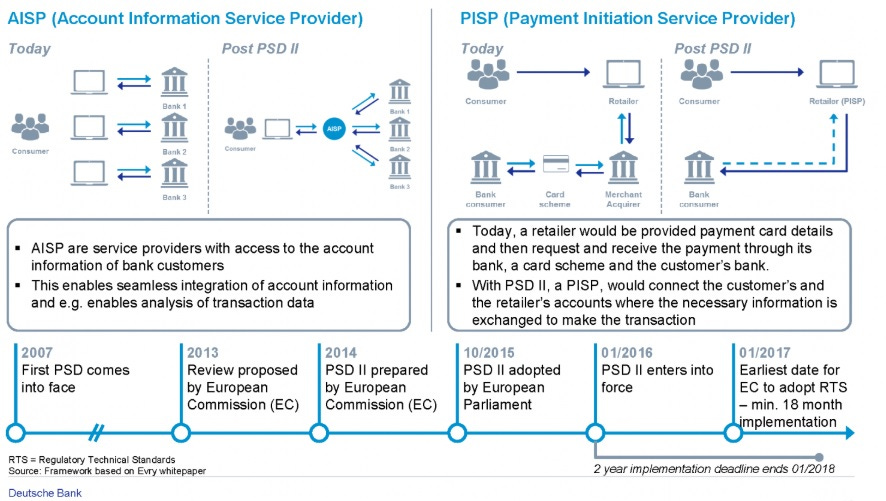

In Europe, you have open banking and a mandate to deliver the data of customer transactions to third parties and to fintechs, and to make sure that there are APIs from the large financial institutions. In the US, it's much more difficult, or at least historically it's been more difficult, and, as a result, more expensive to get access to that data. If it's expensive to get access to it, then that hurts your ability to build the business model, and your subscription has to be more expensive so you can cover your costs and so on.

So that's step one in the infrastructure question is data and data access. Step two, of course, is banking or pseudo-banking services through embedded finance. But maybe let's tackle the first one is what's the state of being able to get the data that you need and what's the ideal state?

Zuben Mathews:

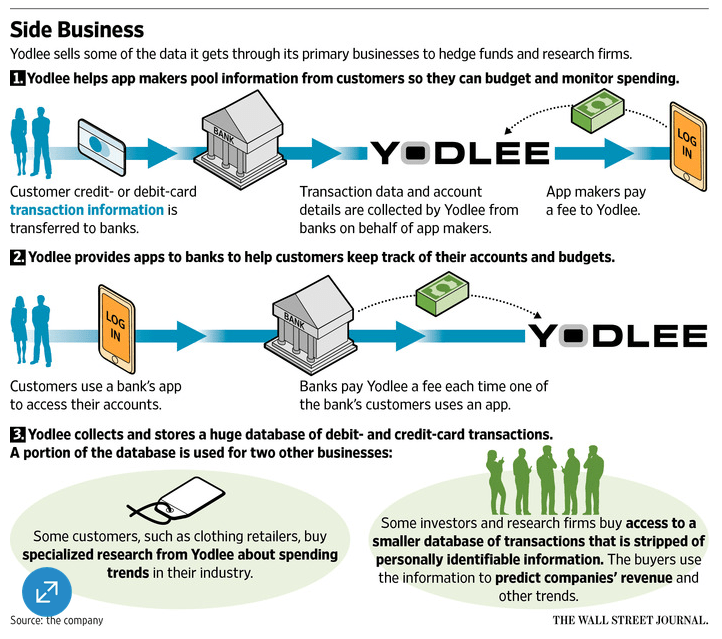

The good news is that even in the United States, going back to companies like Yodlee, there was always a system in place to get access to bank transactional data. The reality is ... You brought up Mint again, rest in peace. They were using Yodlee back in the day, but it was all screen scraping.

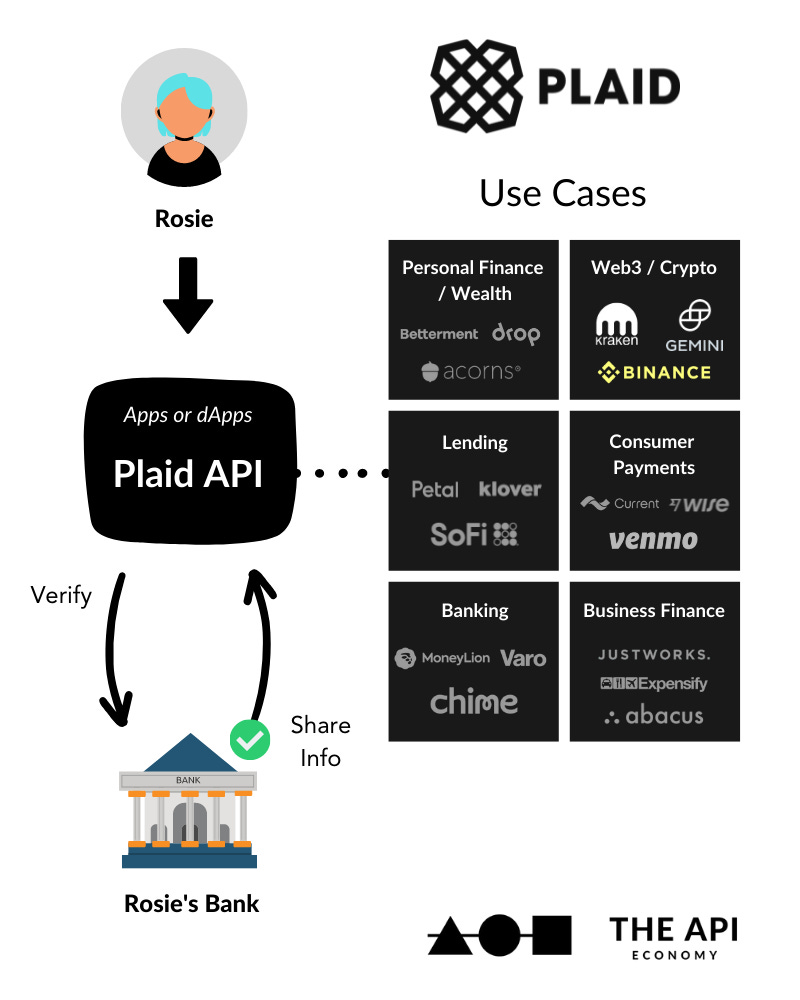

The United States has been behind Europe with the PSD2 compliance and things like that for several years. But, fortunately, with the onset of competition, you have companies like Plaid, who we use, who's done a phenomenal job to just solve what is a deep problem, being able to connect to 10,000 odd banks, and provide companies like us data.

We, at least at Brigit, also have our own middleware setup where we connect directly to certain banks as well. But look, the reality is I would love for, at least in the United States, pretty much every single bank, whether it's Chase, PNC, and whoever else, to say, "Hey, this data is truly owned ... " also with the regulators and the CFPB, owned by the end customer. It is the obligation of the banks, it's not their incentive until recently, to provide direct, simple access for companies like us so we can actually help serve the end customer in the best manner.

If the regulators and the banks do what we all should be doing, which is focus on what is best for the user, what is best for the overall customer, then they would end up doing a lot more and things a lot faster for being able to provide a lot more direct APIs.

At this point in time, obviously companies like Plaid are doing a phenomenal job, as I pointed out, but it would be absolutely great if we in the United States would be working a little bit more like Europe, where APIs were fundamentally open, ideally free or just at cost for companies like us, to connect directly with the banks. I think we're quite a bit far from that, but things are working reasonably effectively. But, hey, let's see what happens in November.

Lex Sokolin:

Yeah, I can say this out loud, and I think many fintech CEOs can't, which I think would be fantastic if the combined weight of the OCC, CFPB, FDIC, and SEC was spent on figuring out how to open up bank data monopolies and financial product access monopolies so that tech companies could build on it, rather than chasing those tech companies around and trying to prevent them from being able to build on a solid foundation, which, of course, takes me to the other difficult topic in US embedded finance, which has been the collapse of Synapse and the echo effect on banking as a service, and companies like Evolve, which are in bankruptcy proceedings and litigation and so on, where we're going now not just from read access in the Plaid, Yodlee world, but in read/write access.

Again, in Europe, you've got all of this within open banking legislation. But in the US, we had to create middle platforms like Synapse and others or integrate into specialty banking as a service banks that try to enable financial products for fintechs like Evolve and others.

That was really fragile because the integrations between all these things are ... Using the type of technology that you described, Deutsche Bank and Goldman are still struggling with. So, when you get down to the size of a small bank that doesn't have the technology budget of a large investment bank, things are even more difficult. The ledgers don't reconcile and so on. But as a fintech, you're forced to use this Lego piece.

Can you talk about downstream from data aggregation? What has been your experience building into the banking rails? What have you been able to do and, again, what does good look like to you?

Zuben Mathews:

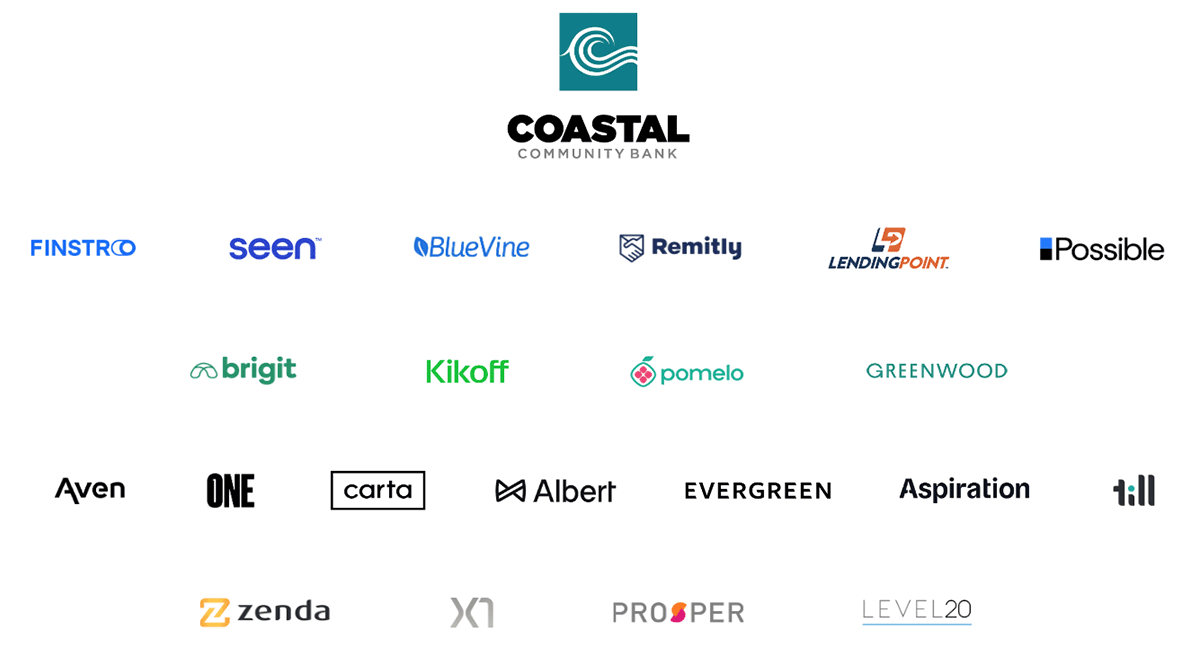

Well, for starters, we haven't used Synapse or banking as a service at all. So just as a footnote there. We, at the end of the day, use a payments processor, as well as a bank underneath that, to send the instant cash product that I pointed out. For our credit building product, we help, again, build people's credit scores by savings. So quite a magical product relative to forcing people to spend to build a credit score. We use Coastal Community Bank as the underlining bank of record to help on that particular product.

Look, the reality is when we started working with Coastal, we signed an agreement four years ago, give or take. The reason why we chose them, because at that point in time, I'm sure pretty much even now, they were among the most, how should I say, rigorous in their selection process in terms of being able to choose their banking partners, which is one of the things we like the most.

It would be wonderful if fintechs in the United States had a plethora of tier one banks, JPMorganChase, whatever, who would also help provide these services. The reality is those larger institutions haven't really stepped up, again, at least in the past.

It comes back to, whether it's the data conversation or the overdraft conversation we had, they've historically not had the incentive to do so because they would be providing the infrastructure to compete against themselves, and that's one of the reasons why these larger banks haven't actually played in that space.

What I would love, and I'm sure some of my fintech colleagues would say the same thing, is a lot more regulation in terms of how these smaller banks as it were, or even the larger banks, would work with companies like us. But that regulation shouldn't be overregulated. I think the problem here in the United States, actually probably everywhere, is it tends to be either under regulation or overregulation, and if something happens, in this case, this horrible situation with Synapse, people end up going way towards one side of the fence.

If we, again, get our regulators, and you've named quite a few of them, in the United States come in and say, "Hey, I'm only going to focus on what's the best solution for the customer while keeping innovation in mind," because the best solution for the customer is not doing nothing and protecting them from all of these fintech bank partners. The reality is ... And it's a very, very tough way to balance this, is, again, start with the customer. What does the customer need and what is the most fair thing for the customer? Guess what? Most of that means inclusive of innovation and providing strong guidelines and correct actions for the infrastructure that sits in between.

Now it's easy for me to say this because this is something that, at the end of the day, I want and, quite frankly, it's in the best interest of the end consumer, but until the regulators, because it does come back to the regulators, focus on the best solution for the customers, be it data access ... And we've been talking about this. Again, PSD2 in the UK probably, I think it was 2014 when it was kicked off. It was, "Hey, this data is owned by the customer." The regulators went and said, "We're going to try to make this the best possible."

The US tends to lag in that, unfortunately. So sorry for me to say this in five different manners. We really do, especially after what's happening with Synapse, need the regulators to come in and provide a much stronger set of guidelines, but guidelines that are focused on both, innovation with the end customer's benefits in mind. Clearly, I'm passionate about this, as you can tell.

Lex Sokolin:

I think now is the moment. The political landscape has never had the, I think, tech industry, the fintech industry, as well as the blockchain and Web3 side of the world so engaged in politics. It's interesting for me to see that the things we're talking about become an issue that they're now being expressed in policy desires. I hope that that's going to be an opportunity for both parties to incorporate a more innovation-first agenda.

Zuben Mathews:

Yeah, but the reality is why should we have to wait so long? It always takes something to blow up in people's faces to say, "Hey, this is what we should do." Unfortunately, what my concern here is is that it'll go to the extreme side of the House, whatever that might be.

Lex Sokolin:

That's a very fair point. Well, thank you so much for taking us through the journey and opening up these topics. If you want our listeners to check out you or to learn more about the company, where should they go?

Zuben Mathews:

In the United States, take out your phone, whether it's on the Google Play Store or the App Store and type Brigit, B-R-I-G-I-T, because it helps bridge the gap between your financial now and the financial future. That's one way. Or call Bless, B-R-I-G-I-T, .com, and we'll give you access, and you can connect your phones to the app by that way as well.

Lex Sokolin:

Zuben, it's been a real pleasure. Thank you so much.

Zuben Mathews:

Thanks so much, Lex. Appreciate the time.

Postscript

Sponsor the Fintech Blueprint and reach over 200,000 professionals.

👉 Reach out here.Read our Disclaimer here — this newsletter does not provide investment advice

For access to all our premium content and archives, consider supporting us with a subscription.

![What Percent of Startups Fail? [Success Advice from Founders] What Percent of Startups Fail? [Success Advice from Founders]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb36e4d86-3ffa-45ed-becc-6063df22dd28_1720x1308.png)

Podcast: Brigit's journey to $100MM+ revenue and $1B in fees saved, with CEO Zuben Mathews