Hi Fintech Architects,

Welcome back to our podcast series! For those that want to subscribe in your app of choice, you can now find us at Apple, Spotify, or on RSS.

In this conversation, we chat with Vishal Garg - Founder and CEO of Better, an all-in-one digital homeownership company. From finding a real estate agent and getting a mortgage, to shopping for homeowners insurance and title services, Better and its affiliates take customers through the entire homebuying process online.

Vishal is also the Founding Partner of 1/0 Capital, a credit and financial technology incubator where he has been a member of the founding team and currently serves as Chairman of Climb Credit, The Number, and Phoenix Holdings. Previously, he was co-head and Managing Partner, ARAM ABS Group ($6 B+ assets) and the Founder and President & CFO of MyRichUncle (2005 NASDAQ IPO), which he founded at the age of 21 and built into the fourth largest private student loan originator in the US. Prior to MyRichUncle, Vishal was an analyst in the Mergers & Acquisition dept. at Morgan Stanley, a frontier emerging markets portfolio manager for the Strategies Fund. He is a graduate of Stuyvesant High School and a Deans Scholar at NYU Stern where he graduated with highest honors.

Topics: fintech, mortgage, digital lending, digital mortgage, SPAC, interest rates

Tags: Better.com, Better mortgage, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Goldman Sachs, SoftBank

👑See related coverage👑

Fintech: CFPB rules BNPL = Credit Cards, must comply with Truth in Lending Act

[PREMIUM]: Long Take: Down from $6B to $500MM, better for Better Mortgage to stay private

Timestamp

1’33: Revolutionizing Mortgages: Vishal's Journey from Frustration to Fintech Innovation

6’41: Cracking the Mortgage Code: Leveraging Fintech Experience to Disrupt a Stagnant Industry

11’11: Overcoming Startup Challenges: Innovating in the Mortgage Industry and Securing Early-Stage Financing

15’25: Recruiting Top Talent: How to Attract High-Caliber Professionals to Revolutionize the Mortgage Industry

20’32: Scaling to Success: The Rapid Growth, Economics and Strategic Milestones of Better Mortgage

24’48: Balancing Growth and Profitability: Navigating Blitz Scaling and Cultural Shifts at Better Mortgage

28’17: Understanding the SPAC Process: The Market Conditions, Expectations, and Challenges of Going Public

34’20: Facing Macro Headwinds: The Declining Efficiency and Financial Challenges in a Changing Market

36’50: Balancing External Stressors and Internal Efficiency: Navigating Market Changes and Organizational Challenges

39’04: From Private to Public: Better Mortgage's Evolution, Current State, and Optimistic Future

43’11: Overcoming Market Shifts: Vishal Garg on Better Mortgage's Resilience and Path to Profitability

45’30: The channels used to connect with Vishal & learn more about Better Mortgages

Illustrated Transcript

Lex Sokolin:

Hi, everybody, and welcome to today's conversation. I'm really excited to have with us Vishal Garg, who is the CEO of Better Mortgage. It's an absolutely fascinating story of the founding of a Fintech company, its incredibly quick growth, and then the many challenges that come with becoming big, going public and navigating the capital markets. I'm really looking forward to this conversation. Vishal, welcome to the podcast.

Vishal Garg:

Thank you so much, Lex. Thanks for having me. I'm happy to be here.

Lex Sokolin:

My pleasure. Let's start at the beginning of the company, and I always love to understand the motivations and the ideas that went into the making of the thing. Can you talk about the initial idea you had, where it came from, and sort of what in your background prior made you feel like, "All right, this is a thing I can do?"

Vishal Garg:

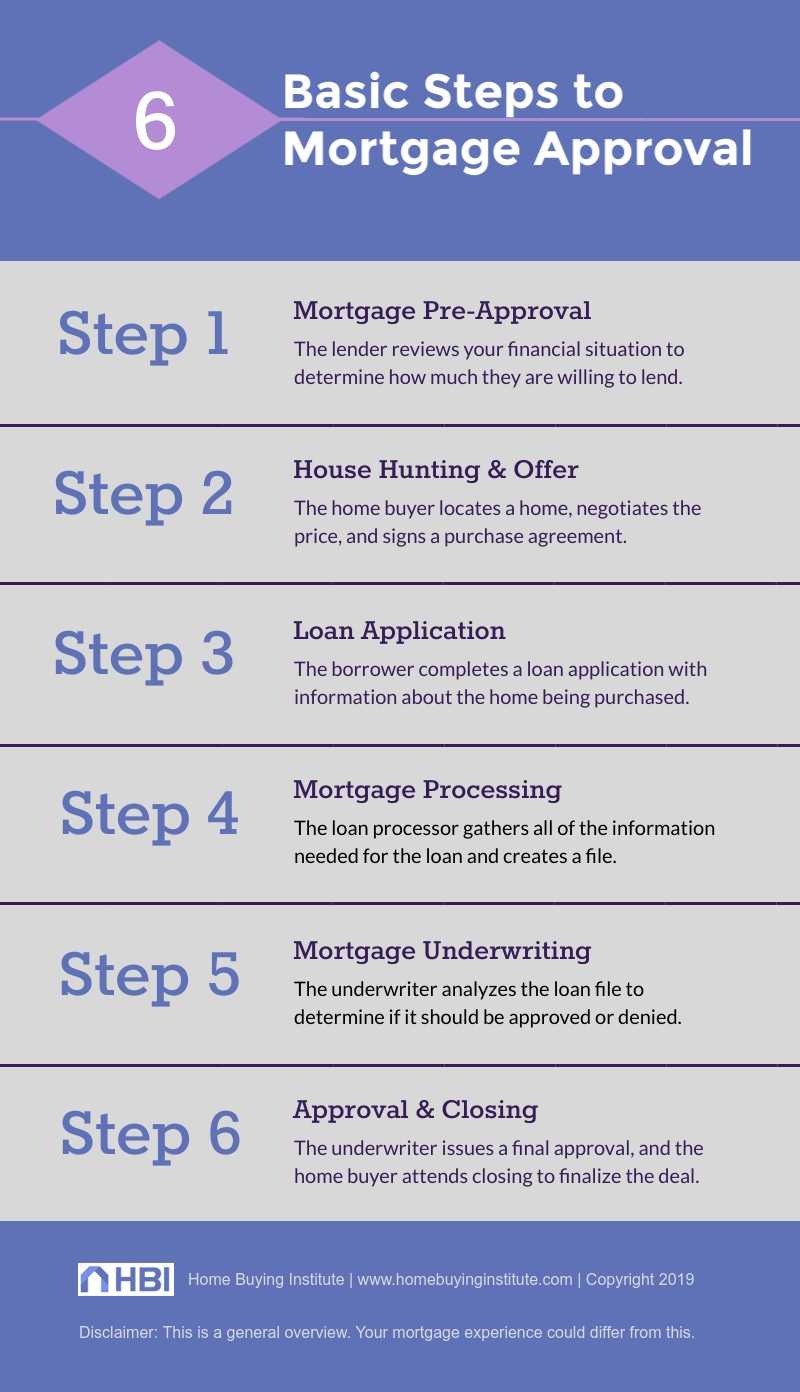

My wife and I were shopping for homes back in 2012, 2013, and we went through the process of trying to find them. Even though we were just coming out of the credit crisis, it was still hard to find a decent place to live in New York at the right price. when we finally found one that worked for us, we were super excited. I said to the broker, "Look, we'd like to put a bid on this place," and he asked, "Are you going to finance?" I said, "Yes, of course I'm going to. Finance rates are pretty low, so I'd love to be financing." He's like, "Well, do you have a pre-approval letter?" I said, "No, what is that?" He said, "Well, you need to have a pre-approval letter if you're going to put in a bid with a financing." I said, "Okay. Well, I'll go and get a pre-approval letter." He said, "Okay."

That evening, I went online, and I put my information into a couple of websites. I went on LendingTree, I went on Chase.com, I went on Citibank, and I went to a bunch of places, and I put my information in, and each time I put the information in, basically they come back and say, "Hey, thanks. Someone is going to be in touch with you shortly." I was like, "What do you mean?" It was already 2013.

The internet had been started almost 20 years ago, and I was so surprised that I couldn't get approved, like, "Well, I could get approved for an installment loan, I could get approved for an auto loan, I could get approved for a student loan online." I was so surprised that it would be difficult to get approved for mortgage online. Then my phone started blowing up, and all these mortgage brokers and mortgage loan officers started calling me the next morning, over and over and over again, saying they were from X mortgage or Y mortgage or Z mortgage, and I couldn't differentiate between any of these companies, so I sort of shut down and I put the whole thing away.

Then my wife asked me a couple of days later, "Did you get the pre-approval letter and send it onto the broker?" I was like, "No. I've been trying to get the pre-approval letter." Ultimately, she's like, "Why don't we try this?" She was working at a major bank at that time. They had something for the bank's senior employees, so I said, "Okay, fine. Why don't we try that? Maybe that process will be easier."

We got called into this bank's branch office on Park Avenue and in Midtown, and we sat together for an hour-and-a-half with the loan officer, and they asked me all these pieces of information. It's like, "Okay, we're going to pull your credit report, or do you have your pay stubs?" I was like, "My wife works at this bank. You have the pay stubs right here in this building. Can't you get them?" Then the guy went in and effectively looked at a whole bunch of things and came back with a stack of papers and said, "We think we'll be able to get back to you in two to three weeks." I said, "No, I need a pre-approval letter now to get to the ..."

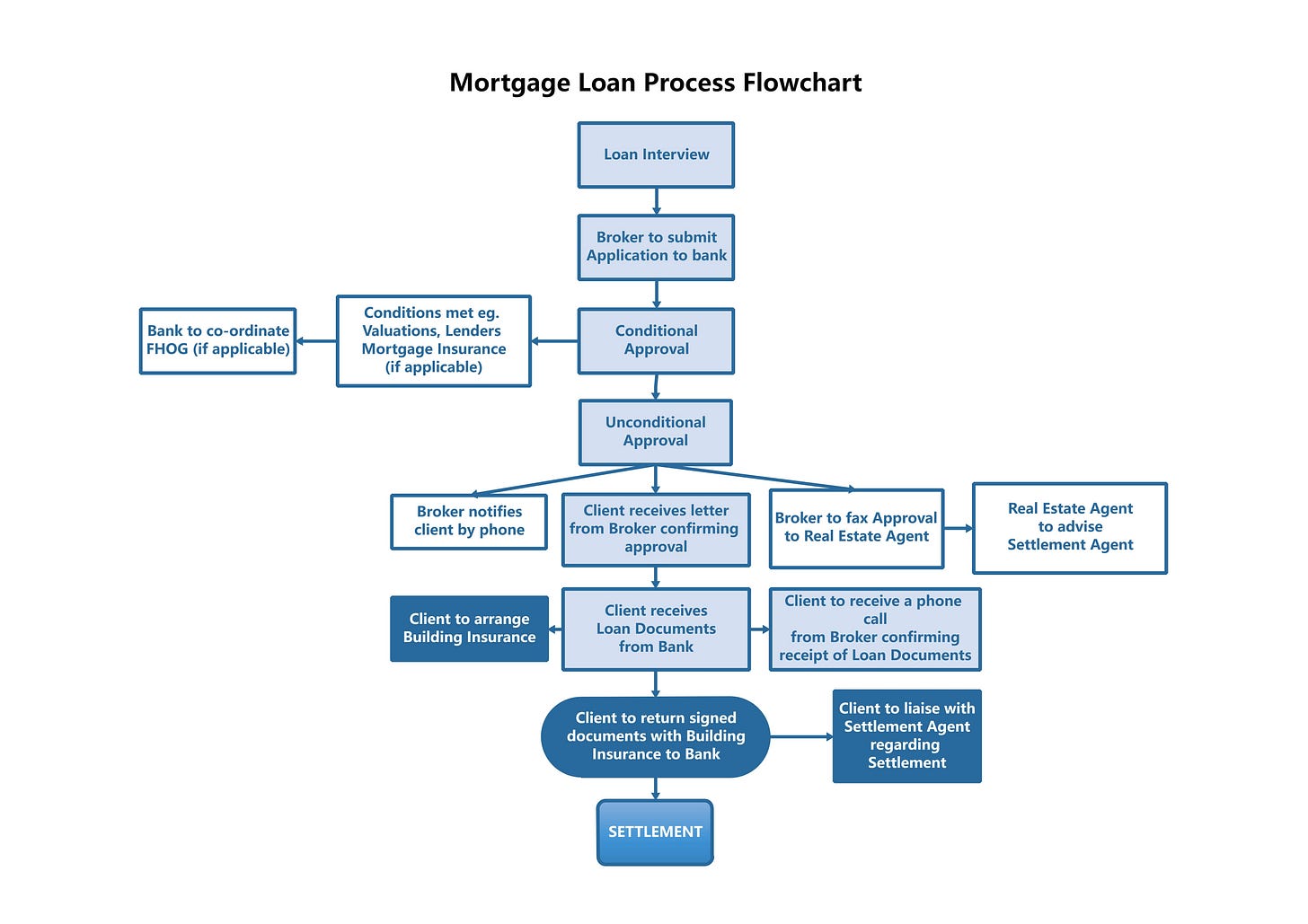

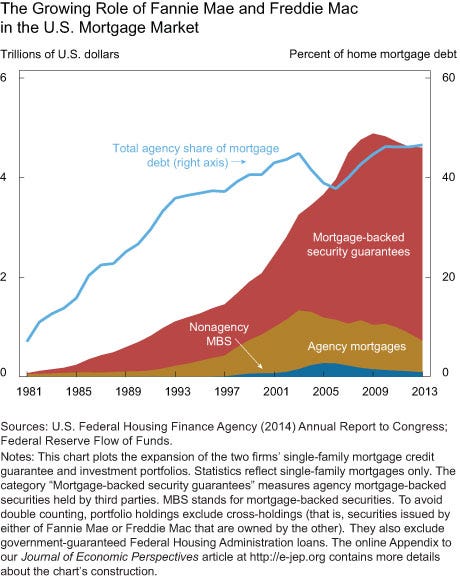

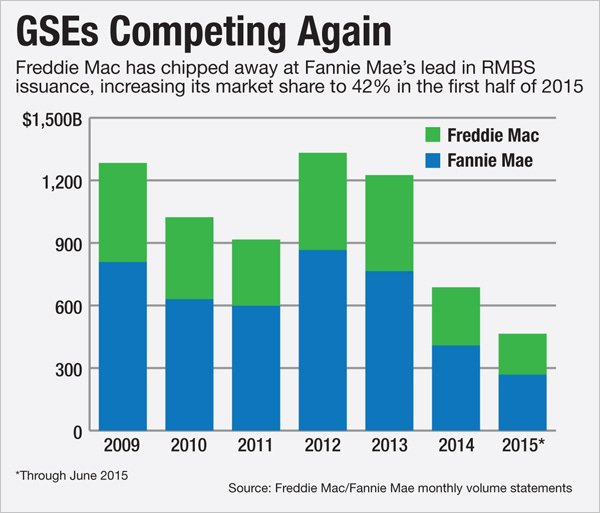

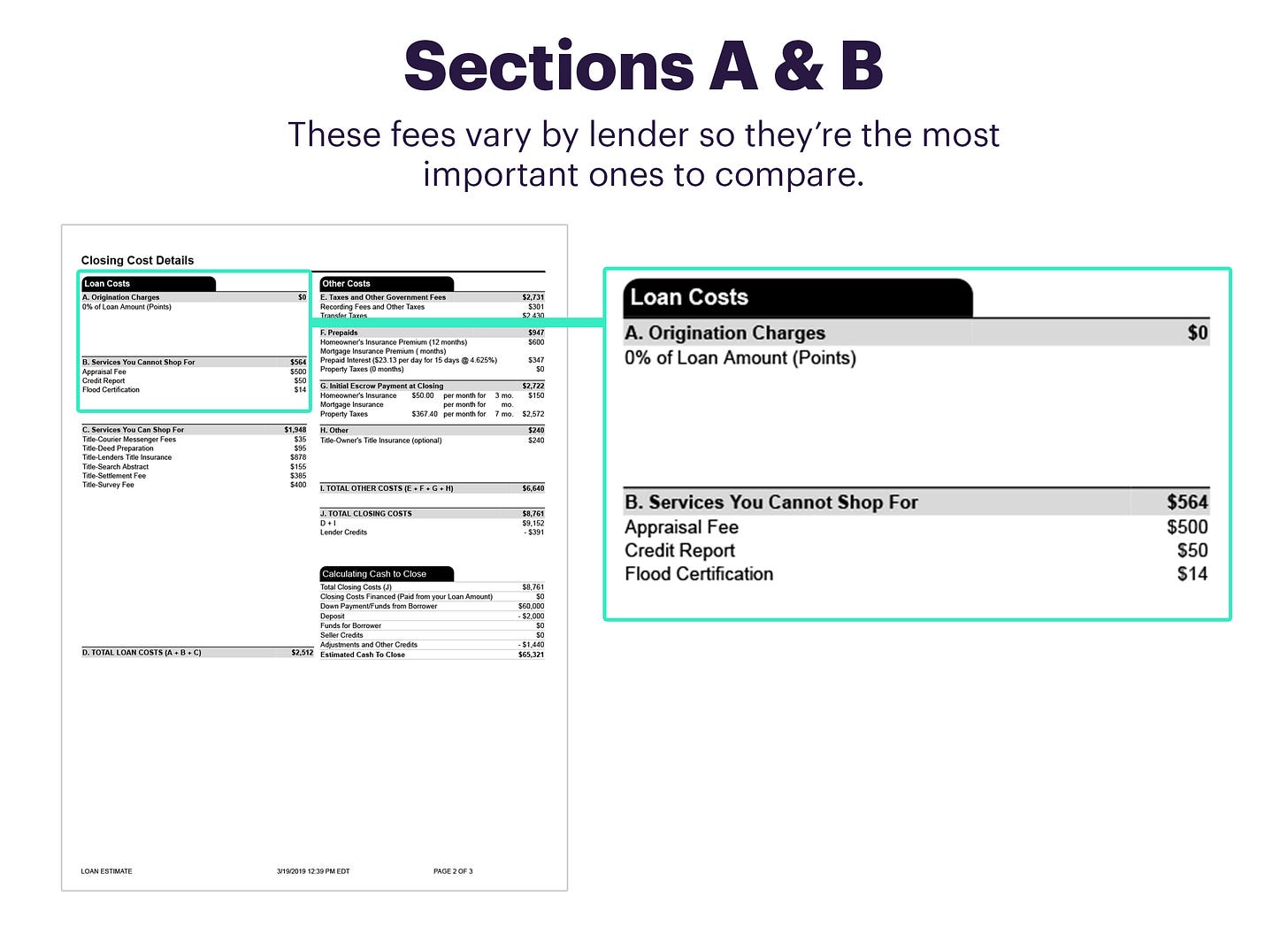

Ultimately what ended up happening is the process was so slow, everything went really slow, and we lost the place we were going to buy to an all-cash bid. I thought to myself, "I can't believe this is so bad. Why isn't this better?" All of this data that they were trying to get is available from third-party data sources, your income, your credit, your assets, all these things are available from third-party data sources and aggregators. Why couldn't this be a process where you permission these third-party data aggregators to give the information to the bank, and immediately you're approved for a mortgage, because I know it's just basically rules that were written by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac?

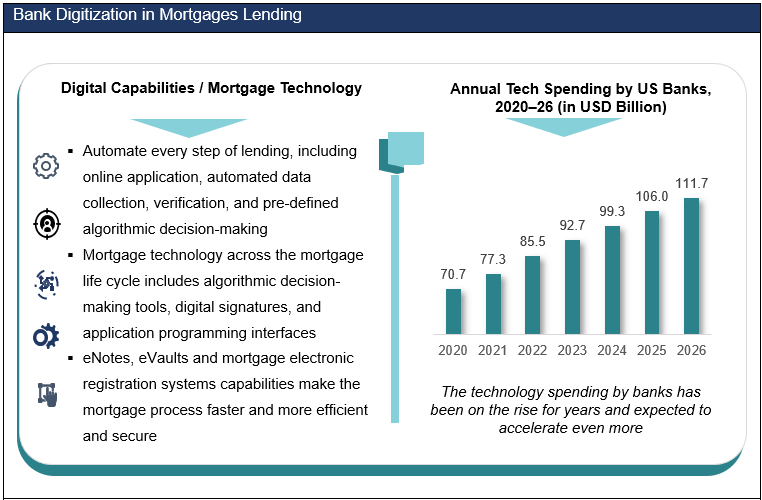

I knew enough about the system. I had been a Fintech entrepreneur. I had started the first online student loan company. Then I had worked in mortgages as a distressed debt trader, trying to figure out which mortgages were good to buy, and which mortgages were bad to buy. I said, "If we can figure out which mortgage in a trust and how much it's worth based on the attributes of the loans and getting the current data in seconds when we're trading mortgage bonds, why can't we approve a loan in seconds when a consumer is trying to get one?"

Ultimately that led me to the insight no one else in the mortgage industry was doing this. All the banks were focused on what had happened in the past with the financial crisis, and so under-investing in their mortgage business and certainly under-investing their technology. All the mortgage brokers and mortgage lenders that used to be out there in the old days before the global financial crisis, Countrywide, Ameriquest, IndyMac, all of the innovators, they'd all gone bust. I was like, "This is a perfect opportunity to reimagine the mortgage industry from scratch and the process from scratch and make it work for the consumer," and that is why I started Better.com.

Lex Sokolin:

That sounds painful, and in many places in the world, it's still how it is, except sometimes you put in lawyers in there as well.

Vishal Garg:

They're paid by the hour, so they're not going to make it go any faster.

Lex Sokolin:

No, no. Can I ask in terms of your skillset at that point, the mid-2010s, you said you'd been an entrepreneur, you were involved in the capital markets a bit? What were the jigsaw puzzles of your career that made you feel like you could do it?

Vishal Garg:

I felt like I knew how investors would react to a digitally originated mortgage, because they had become familiar through the early 2000s with digitally originated student loans, digitally originated personal installment loans, digitally originated auto loans, so I felt like there was investor appetite for this. From a regulatory standpoint, there was a desire for consumers to be able to shop online and have access to information and know what they're getting into when they're getting a mortgage so that they could better understand affordability. From an origination standpoint, I'd created the first online student lender, and basically the thing that was different between an online student loan and an online mortgage whereas that there was also an appraisal. In a student loan, you had to get the credit, and you had to evaluate the parent's income, and then you had to compute the debt-to-income ratio. All of the major things that you had to do in mortgage for the consumer, you had to do for student loans as well.

I knew that the automation of that process could be done for the consumer side, at the very least, even if the appraisal was still human based. Then I had built a company and successfully taken it public before, the student loan company that I started, My Rich Uncle. I felt like it paid to be bold and disruptive, an industry that was very staid and mostly driven by government incentives or government-sponsored enterprises, like Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, because the student loan landscape had been very similar where you had Sally Mae used to be a government-sponsored enterprise that was then later privatized, but the entire landscape was dominated by these federal entities, and so they were big, but they were not innovative. There was room for a disruptor to come in and change the landscape.

Lex Sokolin:

I know a lot of the feedback I'd gotten about the digitization of Fintech in that timeframe, there was a lot of analogous stuff going on. You had robo-advisors turning financial advice into a mobile experience. You had InsureTech come out with digital insurance products. Like you said on the lending side, you had student lending and you had more digital cards and lots of stuff in PayTech. I think people were getting used to having financial products distributed to them through the web and through the phone, but in the air, the reputation of mortgages was that it was really hard to touch, and it would be the last asset class on the lending side to go. Why is that? What about mortgages would make it hard for a startup to deal with?

Vishal Garg:

I think the capital involved itself was large, and there was no ability to pursue a deal with a nationally chartered bank. You literally had to get licensed in all 50 states, one by one. The capitalization requirements, your average student loan is $5,000 to $15,000. If you're making it for college, maybe $20,000. Your average mortgage is $400,000. So to get to scale, you'd need a lot more capital and you need to be able to get eligible with Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, because otherwise, you'll have a high cost of capital compared to the market, and most Fintechs had the value proposition of, "Hey, we're using digitization to lower the cost, and so we're going to pass on that savings to you, so we're going to be a low cost provider."

But if you couldn't get approved with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, you were consigned to doing non-conforming or subprime mortgages, and the TAM wasn't nearly as big. The TAM was with being able to get approved by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and it was a recursive loop, because Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac would only approve you if you had three years of profitability. If you were a Fintech, you couldn't actually access the largest part of the market until you had three years of profitability, and so it was very hard to crack that nut.

Lex Sokolin:

Let's go into phase one of the company where you are figuring out how to break down these challenges and where you see things working and scaling. Can you talk about how did you get around the three years of profitability, and then as you look at the product, what were the things that were important to build out? How did you sequence that?

Vishal Garg:

Yeah, totally. I think I realized very soon that starting from scratch and starting a mortgage company from scratch wasn't going to work because of the need for three years of profitability. I started looking for mortgage companies that I could buy that I could then radically transform. I was looking for big mortgage companies and small mortgage companies. When I was talking to a lot of the private equity guys, who wanted to provide financing for a mortgage disruptor, they were like, "Let's buy a really big mortgage company," and I was like, "Well, if you buy a really big mortgage company, you're not going to be able to disrupt it inside because there's just going to be all this legacy."

I was trying to find the smallest mortgage company to buy, and ultimately, I found a small mortgage lender that was licensed in one state, in the State of California, that had a track record of profitability. They had been profitable through the financial crisis, which was rare, and then had the ability to go get licensed with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. They didn't have their Fannie-Freddie licenses yet, but they had all the capabilities to go get licensed with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. I struck a deal where I would buy that company out, and concurrently, I would raise a large amount of capital so that we had the capitalization for the combined company. We would have TechCo and MortgageCo, we'd have the combined company be able to go get licensed with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. That's how I hacked the requirements for Fannie and Freddie was I bought an existing mortgage company.

Lex Sokolin:

What was the unlock on getting the private equity guys to say yes? Because there's lots of people who are like, "I want to do an aggregation of name your midsize financial services provider and then put a tech platform in. It's going to be amazing." But I imagine that those firms hear that a lot. What were the relationships you needed, and what was sort of the unlock there?

Vishal Garg:

I think the biggest unlock there was I was just doggedly pursuing it. We met with all the venture capitalists, and the venture capitalists, all the big ones were like, "You should just do this from scratch. We will finance you to do this from scratch, but we're not going to finance you to take our money and buy an existing player." Then all the private equity guys were like, "Well, we can't have this crazy burn on the tech side that you're going to have. We need to leg the tech in slowly." Well, if you let the tech in slowly, it just becomes another slightly better version of the existing stuff that's out there, so I didn't want to work with them.

Ultimately, what I was able to do was get Goldman Sachs’ mortgage department, and Goldman Sachs' Venture Investments Division that made investments on Goldman Sachs' own balance sheet to be interested, and so they led our series A. With Goldman interested and blessing the platform, the strategy and the idea, I was then able to get a bunch of venture capital firms to put in some money and a PE firm to put in some money and altogether raise a series A that was $30 million in size. That also then bought out the mortgage company and put all of the things together all in one place. To get everybody together, I basically had to convince a bunch of really smart engineers to come and work for me on this project before they knew that the series A could be fully raised.

We got the engineers together; I got the former head of machine learning and the creator of the recommendation algorithm at Spotify to come on as my CTO. I got a product manager from Google who had worked on Google Maps and Google Docs to come on board as our head of product. I got a few engineers, and we started working on the prototype of the product in conjunction with the small mortgage bank that we were going to buy, and there we leveraged our relationship to get in there and essentially do work for them for free to start to show automation and how we could improve the customer experience. All of that together resulted in a sense of momentum that resulted in us being able to get a deal done. I think that's the biggest thing is momentum, that this idea that we're not going to stop, we're doing this, so either get on board or be left behind that helped us raise the financing.

Lex Sokolin:

Curious as to how you got the talent in. Maybe this is a question on recruiting and persuasion, but if you have an idea and maybe a term sheet, how did you recruit such high-quality talent?

Vishal Garg:

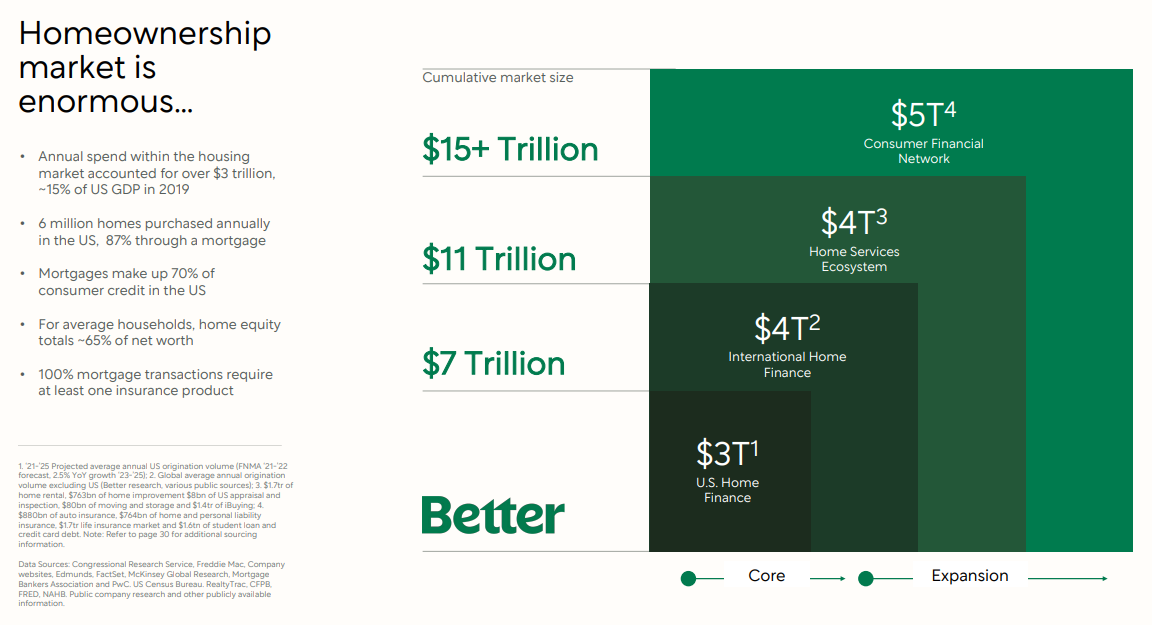

I knew that we needed the best talent, and I think I told them the biggest thing I've always given as advice to entrepreneurs is if you have a massive market that's inefficient and you can define the opportunity, you'll be able to get the best talent. The mortgage market was $15 trillion in size. It was the largest financial services market that had yet been touched us. Residential real estate's $39 trillion, and it's all unlocked through the mortgage business. The idea of creating something that could be a multi-billion, $100 billion-plus company, which is what the divisions of these mortgage companies or these banks are worth, that was a prize that was really attractive to the best talent out there.

I wouldn't say that everyone is attracted to it. Some people were like, "This seems like a too big of a problem to solve," but if you were working on something really big and there's a chance and there's the right people involved and you could get a term sheet and you've got some momentum going, you can get the best people to join, and that's what we were able to do is just get the best people to join. They were a little younger, they were a little hungrier, but they were some of the best people that I've ever recruited, and I was able to do that because we were working on a problem that was so massive.

85% of consumer finance's mortgage, and that was the thing that was untouched. I said, "We're going to go take a whack at it. Why don't you come spend a year, two years with me taking a whack at it? If it doesn't work, at least you tried on a big problem, and then you can work on a small problem. But if you work on a small problem, it's never like you can then go work on a big problem."

Lex Sokolin:

I love your conviction. When you get to the early building of the product, can you talk about the sequencing of what was important to do inside the company and then what was less relevant and you integrated into other providers for? What was the core? Was it the underwriting engine, was it the servicing, was it the distribution? Because you can't do everything at once, so how did you prioritize the software elements for this company to work?

Vishal Garg:

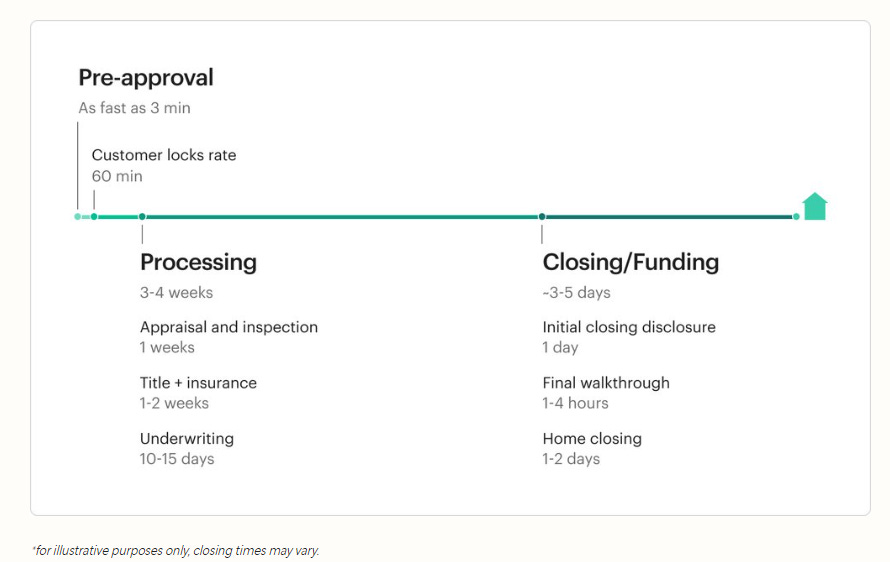

The first thing that we did was what's our value proposition to the consumer? We needed to have a value proposition to the consumer that was easy to understand in one line, and we looked back to my experience, right? Lets find out how much house you can afford in three minutes, get a pre-approval letter in three minutes. We said, "Let's do everything we possibly can to get the experience so that a consumer can get when they're going shopping," which is not when mortgage companies are looking for them. Mortgage companies are looking for them when they actually found the house they bought and all that, but at the early top of the funnel, let's aggregate the top of the funnel as much as we can. "Can we do that, and can we deliver that value proposition to the consumer?"

We did everything we possibly could on the tech side with the team to take the act of pulling credit, computing all of the credit payments that are due, verifying the income that was needed, computing the debt-to-income ratio, and then doing a simple online appraisal of the property address, and put that all in one flow in under three minutes, and that was the goal, and they all ran at that. We were running at that for six, seven months hard.

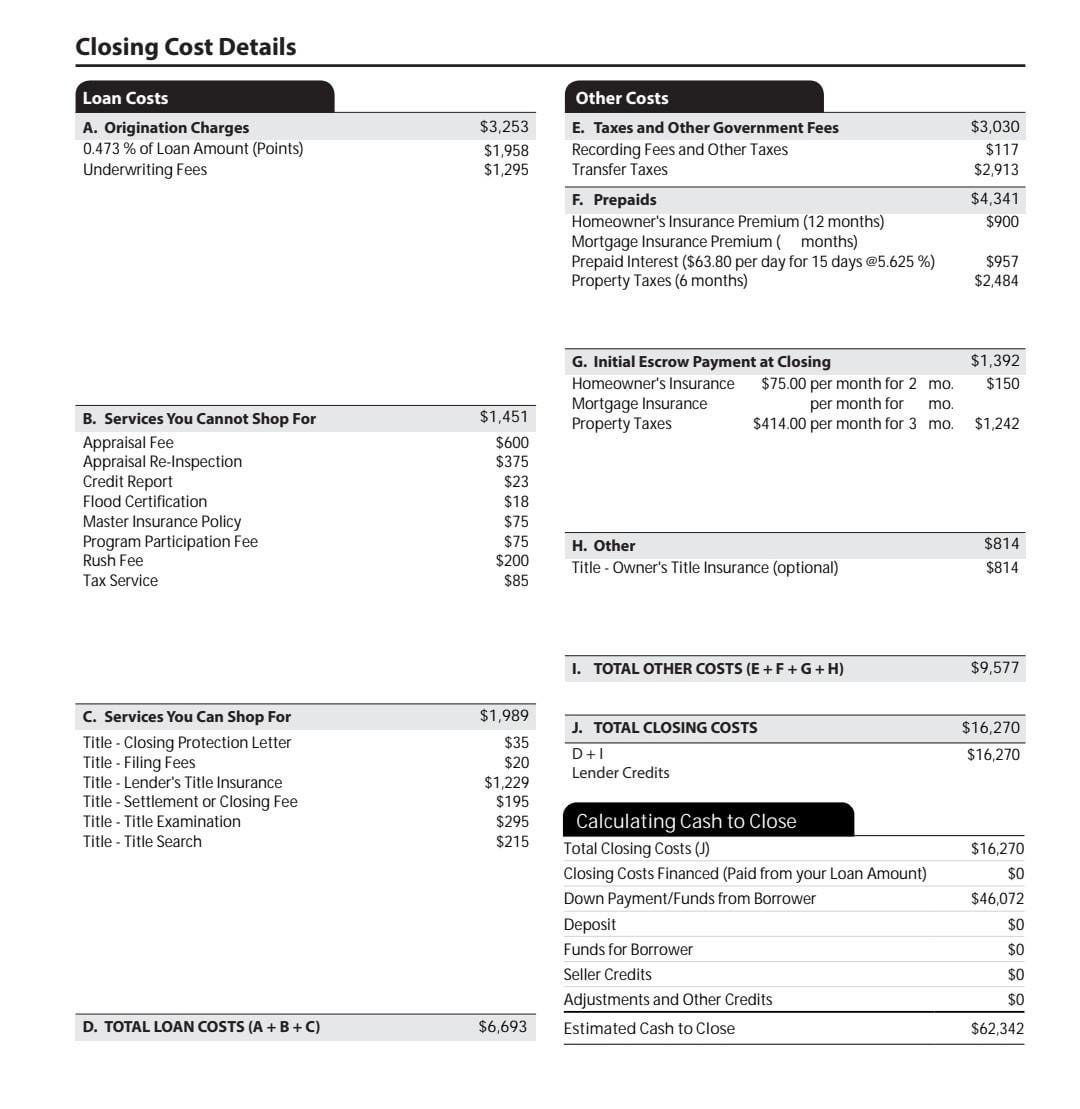

Then on the flip side, when we did show them the rate that they were qualified for, we needed that rate to be lower than the market and what they would get at a major bank, because that would then cause them to stick with us. Not only was it easier, but it was also cheaper. In order to do that, we had to basically figure out how do we get our processing costs and underwriting costs down, and the way that we did that was we actually took a large percentage of the underwriting processing and coordination part of the process, and we staffed up a team in India to do it.

That gave us two things. One, it gave us a cost advantage on those jobs, and two, it gave us 24/7 turnaround time, and so we were able to do the loans faster and do them at a much lower cost. Then we took all the cost savings that we got from that, and we passed 100% of it back to the consumer. That enabled Better to be cheaper, faster and easier. The holy trifecta of how you make $100 billion company in America is it's got to be cheaper, faster, easier is my understanding. That's how you make a Costco or a Walmart or an Amazon. We were able to deliver that to the consumer in 2016 when we launched. That was an amazing value proposition.

Lex Sokolin:

Let's plot the next phase of the company, which I guess would be up to the spec, but not yet on the other side. You had very strong organic growth over that time, you made the company larger, you had much more in terms of originations, in terms of revenues, and then, of course, hiring and growth more generally. Can you talk about maybe not the moment but the neighbourhood of when you said, "Okay, I feel comfortable really scaling this?" And what was it scaling from and what was it scaling to in your mind?

Vishal Garg:

Basically in 2016, we did about $400 million of loans. In 2017, we started automating more of the back-office part of the loan process to make our value proposition more competitive and spent a lot more time on that side than trying to grow, so we did $500 million of loans in 2017. Then in 2018, we were ready to grow. We had gotten the front end of the process and the back end of the process automated, and then we grew 300%. We went from $500 million of loans to a billion-and-a-half of loans. Then in 2018 and then going into 2019, then we went from a billion-and-a-half of loans to four-and-a-half billion of loans. Then from 2019 to 2020, we went from four-and-a-half billion of loans to $25 billion of loans, and then from 2020 to 2021, we went from $25 billion of loans to $60 billion of loans. We literally grew the business by 100X during that period of time into a mortgage company that in 2021 was doing more loans than Bank of America was across all of its branches and its website.

A lot of that was built around value proposition to the consumer and this flywheel of value to the consumer drives consumer adoption, drives cost efficiencies, drives further automation, drives further value to the consumer. We just got that wheel spinning in 2018, and from 2018, it was just bang off to the races. Now, the most we could grow at that time was like 300% a year though in 2020 we grew 600%, 700%, but that was just this flywheel that was working in 2018, 2019. Then in 2020, what happened was the pandemic, and in the pandemic happening, you couldn't walk in in April of 2020 into a bank branch to go get approved for a mortgage anymore. You had to do it online.

The demand went through the absolute roof to be able to do this on an online basis, and so we took tons of market share from all the weaker players in the market who didn't have good digital offerings. That was this boom that took place. Going into 2021, we just continued to play off the same value proposition. I would say the playbook was exactly the same for four years running, and I think one of the things I learned as sort of a second-time entrepreneur is when you get the playbook right, you let it run, and you keep on letting it run, letting it run, letting it run, and it worked for us all the way into 2021.

Lex Sokolin:

That must have been an absolutely exhilarating but very stressful time. When you look at that destination of $60 billion in originations and being bigger than Bank of America, if you look across the company, what are the economics of it at that point of time? What's the revenue? What's your cost base? How are you thinking about hiring and your employees? What are the unit economics?

Vishal Garg:

2020 and going into the first quarter of 2021, the first quarter of 2021, we made about $150 million in profit, and that was on about $15 billion of loan volume. That was our peak. So, $15 billion of loan volume, our revenue was about $300 million, and our costs, about two points or so on the loans, and then our cost was about one point on the loans, and the profit that fell to the bottom line was a point. There were very healthy margins and very healthy unit economics.

Lex Sokolin:

The reason I bring it up is also there was a cultural moment where the SoftBank and Tiger approach to venture investing, which prioritized blitz scaling at all costs, I think you saw it across lots of different companies where the logic was take the market as fast as possible. If we're burning through our balance sheet to do it, that's okay, because we just need to get to a huge scale, and so you had those dynamics in play. How do you remember that time? Was that something that was on your mind? Was it like, "We got to get to a scale?" Or were you more focused on having a more economically viable business, which it sounds like you had the skeleton of?

Vishal Garg:

Before we met SoftBank, we were trying to be our own venture capitalist. Once we broke into profitability in April 2020, we were just trying to make money while delivering value to the consumer. While interest rates were low, we could do that. We didn't think that there would be a cataclysmic change in the interest rate environment where interest rates would shoot up, because interest rates had remained low for a long time. The macroeconomic factors that were there were there. We thought, like everyone was saying, the minor inflation at the time was transitory, and so we just didn't think that there was much changing. We were actually trying to make as much money as possible while the good times were there, knowing that we probably would go back to not making money once COVID went away.

COVID was a profit booster for us. We didn't increase our losses, we started making a lot of money. In 2020, we made about $200 million in the first quarter in profit. In the first quarter of 2021, we made $150 million of profit, so we were increasing our profitability through increased automation and increased all that, and we thought there was a secular trend toward digitization. Then we entered into a deal with SoftBank, and I think the clear mandate was this is a once-in-a-moment step change in the consumer's adoption, and so lean into that and lean into that further.

We did start to lose money leaning into that and leaning into that further. I would also say now I know it, but that growth that was coming at that scale was something none of us had experienced before and weren't fully prepared for. Going into COVID in March 2020, we were a small exec team all together in one place coordinating. Everybody was in the office every day, people were working 9:00 to 9:00, and everything was super transparent, and everybody knew what everybody was doing.

What happened is that changed. In about a year, and you can't imagine a culture changing in a year, but in about a year, it became much more like, "Wow, I've made all this money." There was a secondary of $500 million where a whole bunch of executives got to sell. I didn't, but a whole bunch did in that one. Ultimately, what that meant was people had started getting comfortable, and we didn't have the same fire that we had had before where we were always fighting for survival against these massive incumbents that we were up against. Things started to change, and the culture started to change, and we were just hiring up people.

Also, just as you get to scale, as you grow from a team of 1,500 total people all around the world to 10,000 people, you're hiring standards loosen, you let in people who are much more about the money than about the purpose, and so some of those challenges have started manifesting themselves. As we were trying to strive for the next unit of growth, we were not making money on the next marginal unit that was coming in the door, and that started to show in our financials.

Lex Sokolin:

Can we talk about the SPAC process, and from your seat as a company that chose to go through it, what was the market structure and what were the market conditions that you saw that allowed you to pull the trigger on it?

Vishal Garg:

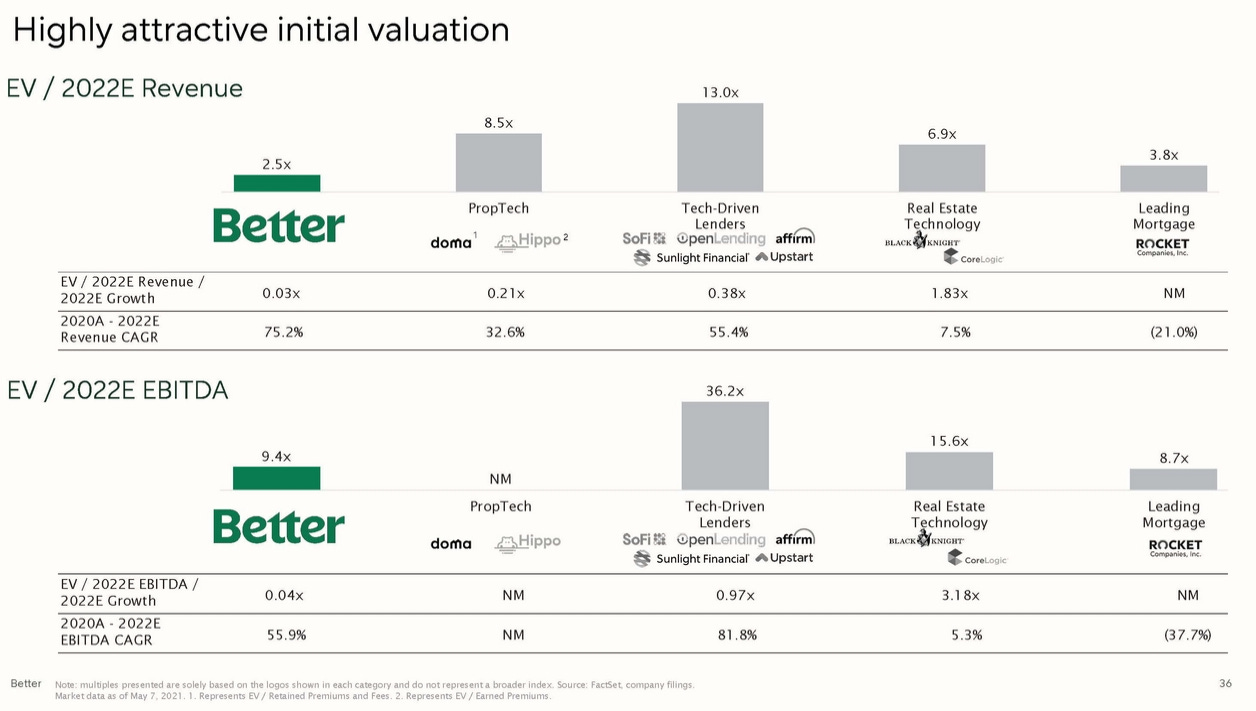

I think at that time we had the chance; we had the opportunity to go public. The SPAC process was something that was introduced to us by SoftBank. They thought it was a superior means of getting public. It meant that a lot of the traditional challenges with the IPO process where insiders don't have the same liquidity, where certain institutional investors get to sell, where there isn't a large float, all of those things were going to get taken care of by the SPAC process. We thought it was actually intellectually a fairer process for employees, for minority shareholders, for others, and so we were enamored with it. That plus the fact that the SPAC process valued the company in a more transparent way at, candidly, a higher price, whereas in the IPO market, you were basically advantaging or giving an advantage to the IPO investors, and then there's usually a first day pop and all that sort of stuff. I just felt intellectually like a better process at that time.

I didn't know at that time that 99% of the companies that were going SPAC were going to have these massive hits and that the SPAC process was not well-diligenced or any of that sort of stuff, but I thought it was an intellectually superior process, and so I was enamored with it and convinced to go forward with it.

Lex Sokolin:

I think everybody was surprised in terms of how it turned out. In particular, on the one side, you had the private markets and the blitz-scaling kind of mantra and the strength from COVID created this feeling that Fintechs would trade at venture multiples but in the public markets. Of course, public investors, equities investors, hedge funds and institutions have been all saying, "All this stuff is just banks. This is all just trading at bank multiples." Because you didn't have the connective tissue between the two markets, it was mostly philosophical question, aside from probably the digital lenders that all IPO'd and then collapsed 80%. But outside of that, you didn't have a lot of examples of at-scale Fintechs going public and then getting repriced, and then you had sort of this, at least for I feel like six months or so, this impression that the venture side was right and that these things would trade at venture multiples, of course until they didn't, and that was a result of the entire re-rating of the equities markets with the macro environment and risk-off and interest rates and so on.

Can you humanize the experience of what that was like? It must have been, stressful is the wrong word for it, but what did you witness taking a company through that process and then being on the other side of it?

Vishal Garg:

It was really difficult. Everybody thinks that they're special, every company thinks that they're special in some way. One of the reasons we thought we could sustain a Fintech multiple from the private markets into the public markets is that we were balance sheet light. We don't hold any of the products, so we don't take any balance sheet risk. The loans we do are Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, FHA guaranteed, when we are just actually an originator and a manufacturer of the product, and we run a full marketplace with 30+ investors, a deep liquid marketplace. It isn't like any of our investors have power over us or anything like that. We run an auction on every single loan. We thought like, "Okay, we're going to be able to do this and we're going to be able to transcend."

I think the reality of the situation was that the markets move and have a herd mentality, and when they love you, they love everyone, and when they don't like you, they don't like everyone, and it's really, really, really hard to withstand that tidal wave when the market's direction changes. For a six-month period between March of 2021 and September of 2021, we really felt like we would going to be able to withstand it, and we continued to have growth, revenue growth. The unity economics were not as good, the profitability wasn't so good, but we had revenue growth and we kept growing.

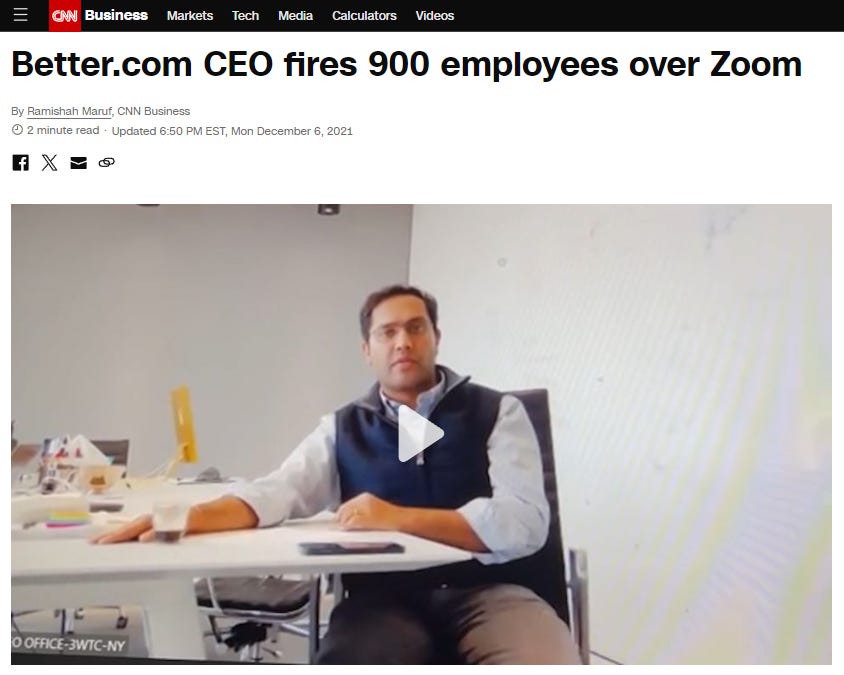

I think where it really hit us was when everybody came back to the office in September 2021. I asked everybody come back to the office in September 2021, and I just felt like the company wasn't the same company before. I think people were still ... It makes sense. We are reading what's happening in the market every day, we're looking at the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, we're reading what's happening, but that's not what the average employee or the average mid-level manager or the average VP is doing, and they're thinking like, "Wow, this is amazing. We've transcended. This is going to be glorious. My shares are going to be worth so much," all this sort of stuff.

I feel like there was this rude awakening that started to happen, and I felt it immediately in September, and I was trying to communicate it to people. It took a long time for me to be able to even convince my senior management team, "Guys, the world is starting to change. We can't keep doing the same things that we're doing before. We can't keep hiring 700 people a month because the growth's simply not there. The next marginal unit of growth is not profitable, and so we shouldn't be hiring more people."

It's like, "Well, what are we going to do with the recruiting team if we stop hiring people?" That's what the head of recruiting is worried about. Well, of course she should be worried about what's going to happen to all the recruiters, but honestly for the company, the company's got to worry about, "Hey, we gone and hired these people, and maybe those recruiters can be salespeople, they can do other things, or maybe they're going to have to move on to doing something else." There was just this avalanche of hard decisions everywhere you looked in the company that needed to start to get made and needed to start to get made really fast.

Lex Sokolin:

What were the macro headwinds for the core business? Put aside growth and the next marginal customer, if you just stayed in place, why was the company not making money at the scale that it was at before? What had changed?

Vishal Garg:

It had become less efficient. We had hired more people, and those people, the marginal person we were hiring, was not as efficient as the people that were there before, wasn't necessarily as into it. They weren't putting in the hours, they weren't as well-trained, they weren't as purpose-driven, and so we had fundamentally become less efficient, which was just really jarring to witness, because you're supposed to get economies of scale. We reached peak efficiency around 6,000, 7,000 people, and then each marginal person that we were getting on board wasn't generating the same level of efficiency in terms of loans processed, loans sold, customer queries answered, any of those sorts of things. What was interesting is our India office continued to grow in terms of efficiency, but our US office actually declined in efficiency.

Then in the beginning I was like, "Okay, people are just taking a break." COVID was receding, and people wanted to go on vacations and people wanted to do these things, and I was very empathetic to that. I was like, "Okay, we've done well. We should take the breaks; we should do all that sort of stuff." But the efficiency of our business had fundamentally gotten to a point where we started to see that if we just stayed in place, we would lose $30 million a month. That's just an extraordinarily large amount of money to lose, to go from making $50 million a month to start losing $30 million a month, and that was not going to be tenable.

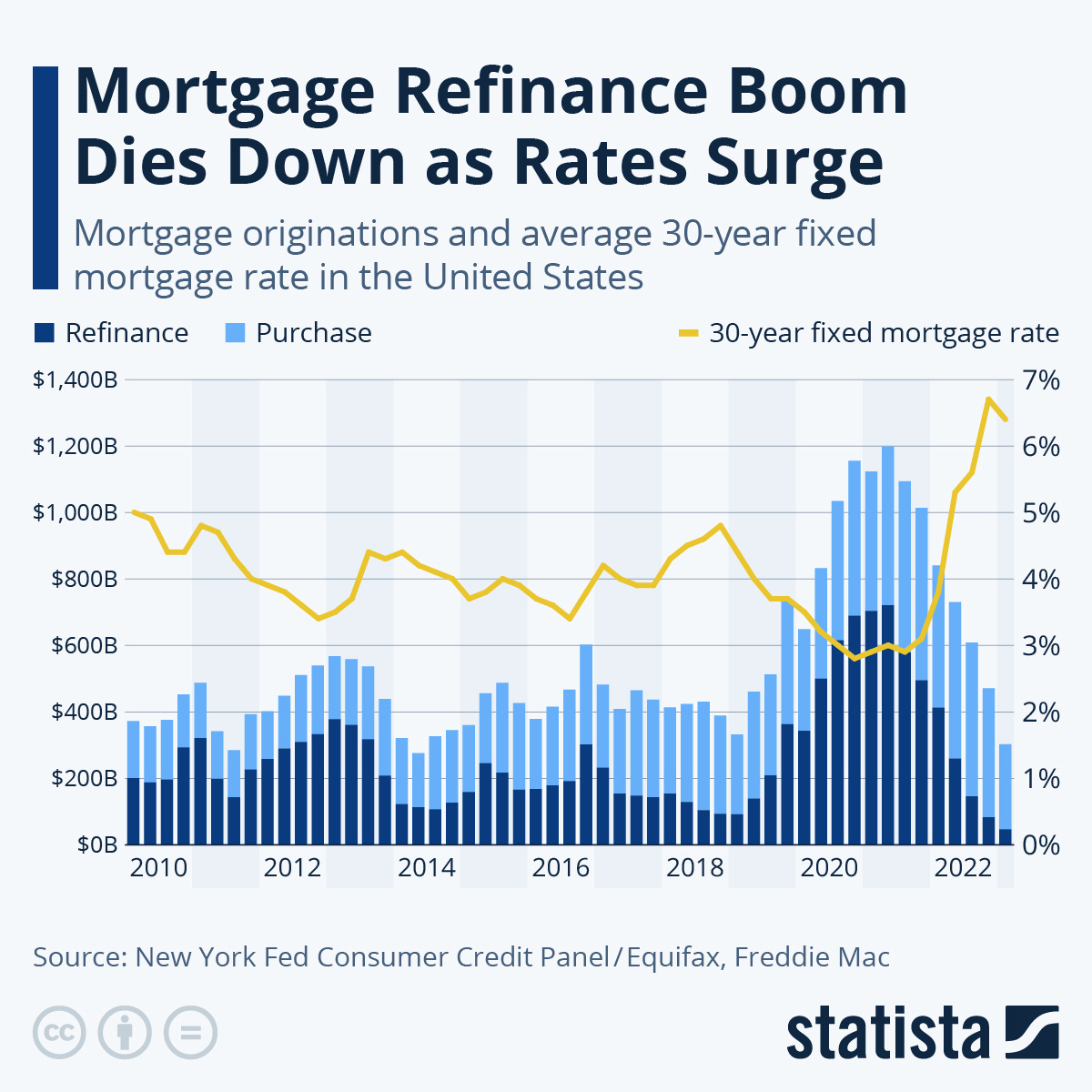

The interest rate environment had changed, and when interest rates go down, they keep going down or they stay down, but when they start going up, they're going to go up for a little while. I could see that the path was not going to get easier. It was going to actually get harder. We were less efficient, the world is changing, interest rates are going up. It means our job is actually going to get harder. The number of customers that could buy a home or could afford a home is going to go down, so our TAM is actually technically shrinking, and that's a rough spot to be in.

Lex Sokolin:

If I have a mortgage at 1%, I'm not going to refinance that at 8%.

Vishal Garg:

That's correct.

Lex Sokolin:

It sounds like there was a confluence of stressors, but if you were to weigh the external stuff, which is the drying up of demand for underwriting mortgages versus the shape of the company and the shape that the company had gotten into, how do you weigh those two?

Vishal Garg:

I would say 60% of it was the external stressors, right? Our TAM was shrinking and shrinking so rapidly and so fast, and then on the flip side, we had become less efficient.

Lex Sokolin:

If you were able to tell this to yourself before you did the SPAC, and maybe as you're signing the SoftBank term sheet, what process or system would you put in place a priori to not make that kind of over-hiring efficiency error? Is it correctable, or is it impossible to avoid?

Vishal Garg:

I think we would've had to say, "Hey, guys. You're buying into a profitable company. Our focus is going to be on profitability and not on growth." But then realistically, if you can't deliver growth, then you can't get the multiple. Exxon is a very profitable company that trades at a very different multiple than a tech company, right? Tech companies that are really profitable but don't have a lot of growth prospects trade at the multiples of utilities. Fundamentally, those two worlds were at odds with each other, and it's just a quagmire. I don't actually know whether I could have done anything differently. The thing I could have done differently was make sure the efficiency of the company did not recede and been much more adamant about the efficiency not receding, even if that would've been an unpopular thing to do. I had to do a very unpopular thing later on. What I probably should have done was do several minorly unpopular things earlier on.

Lex Sokolin:

Let's then land into where the company is today and this last phase where you've gone from the private world, where there's often the next round and you can get this higher valuation, to having to deal with being public, to having a compressed market cap and compressed revenue. Can you talk about what the company looks like today and what you're seeing as the future, the optimism that you have clearly for the business, where it comes from?

Vishal Garg:

We've done so many things over the past two years. We've been in downsizing mode for the past two years. In 2022 and 2023, we were in downsizing mode and efficiency mode. All of the efficiency that we put in place and automation of the mortgage process; we have now taken the mortgage process. We are not talking about taking the 60-day mortgage process that other people were doing, and it was 20 days or better. We literally have the one-day mortgage, and that's groundbreaking. Now, it's happened in a time when nobody really cares what's happening in Fintech land, but literally, we have a one-day mortgage. That's the asymptote to which someone actually needs their house mortgage to close. That's something I couldn't have imagined actually getting to but I've been able to get to, the technology has gotten superior, we're entirely on our platform. We have automated so much of the process to make it so much faster.

What that leaves us with is a cost advantage, vis-a-vis the rest of the industry, where we can say that our cost basis is industry leading compared to any other player in terms of how much it costs us to make a loan. Second, from an efficiency standpoint, and I shared this, we're doing on average 17.6 home purchase loans per loan officer in 2023, and that is 3X the industry efficiency rate. We are really proud from the past two years of all the efficiencies that we've put in place. All the things that we were working towards, we've actually been able to put them in place.

Two, we've pivoted from doing refinances. We used to do 95% refinances and 5% purchase mortgages. We've pivoted that to now we're 90% purchase mortgages, and purchase mortgages, because of the general dynamics, people continue to move and have children and all that sort of stuff that causes purchase mortgage demand to be evergreen, so our business is a lot more sustainable than it was in 2021. Even though it's a lot smaller than what it was, it's a lot more sustainable than what it was in 2021. We are now in a vertical of the mortgage market that's evergreen.

Then the last thing is the team. The team, the warriors, the people that stuck with it through all of the hard times of 2022 and 2023, continue to keep their heads down and just push through all the bad press, through the compression, through the downsizing, and we just have this amazing battle-hardened team that we are now finally starting to grow again. Now, we're doing it in a measured pace. We've got capital. Our last earnings call, we've got over $500 million of cash on the books and a clear path to industry-leading customer acquisition efficiency stats, and we're really psyched for the future.

This last quarter was the first quarter that we grew in over two-and-a-half years. We grew revenue by 25%, quarter-on-quarter. We grew loan volume around the same amount, and so we are now turning the corner on a growth path. It's still very, very, very early days for us to get back to the great heights that we were at in 2021, but we're really pumped about the journey ahead.

Lex Sokolin:

It helps you that you've done this path before, right? You've been at this revenue number, and you've gotten to the next revenue number, and so it's something that you know is achievable. I have two questions on the current state. The first question is whether you were asymmetrically impacted on the refinancing of mortgages, it hurt you in particular, or if you look across the competitors, were other companies similarly compressed in that business line, or was there something in particular that made that product not work for you? Then a simpler question, which is at what scale are you getting to the type of profitability you're happy with again? Or in terms of engineering the business into an economic machine that you feel comfortable with, what's the scale of that?

Vishal Garg:

The first thing is, as an online-only player, we were more asymmetrically affected by the demand drying up because our customers are generally more savvy. The savvier customers, the TAM of the savvy customers who can benefit from refinancing went down faster than the TAM of the overall refinancing market. Now, every one of our competitors is hurt. Almost every one of our competitors lost money last year and the year before, so everybody in the mortgage industry got crushed and demand went down by 70% for some people and 99% for other people. It's just somewhere in between, depending on what percentage their mix was refinanced versus purchased and things like that. We were clearly much more affected, and honestly, the flip side is when demand was going up, we were extraordinarily enabled by the consumer looking online, because the guy at the bank wasn't calling them back fast enough and then coming to Better. We were the beneficiary when the tide was lifting, and then we were much more adversely impacted when the tide receded, so that's one.

To your second question, where we are today, we believe that on a unit economics basis, we're making money on each marginal loan, so we've just got to get back to scale to cover our corporate overhead. As it's a public company now, I can't tell you when we'll be profitable or give guidance on it any which way, but we are very confident in the future ahead, and we see some really positive green shoots in the coming year or two towards driving to all of our goals, which includes profitability.

Lex Sokolin:

I appreciate the amount of grit that it takes to go through this journey. It is a really difficult path to walk, and it's difficult for leadership. It's obviously difficult for employees that are impacted by the volatility. It's difficult for investors, but I think all of that together, it's scar tissue that's likely going to help you build a much stronger company going forward. If our listeners want to learn more about you or about Better, where should they go?

Vishal Garg:

Better.com.

Lex Sokolin:

It's a good domain.

Vishal Garg:

Thank you.

Lex Sokolin:

Fantastic. Thank you so much for joining me today.

Vishal Garg:

Lex, thank you so much for having me on and getting a chance to talk more about our story. We're just getting started, and we really appreciate everyone who's listening, so thank you.

Shape Your Future

Wondering what’s shaping the future of Fintech and DeFi?

At the Fintech Blueprint, we go down the rabbit hole in the DeFi and Fintech world to help you make better investment decisions, innovate and compete in the industry.

Sign up to the Premium Fintech Blueprint newsletter and get access to:

Blueprint Short Takes, with weekly coverage of the latest Fintech and DeFi news via expert curation and in-depth analysis

Web3 Short Takes, with weekly analysis of developments in the crypto space, including digital assets, DAOs, NFTs, and institutional adoption

Full Library of Long Takes on Fintech and Web3 topics with a deep, comprehensive, and insightful analysis without shilling or marketing narratives

Digital Wealth, a weekly aggregation of digital investing, asset management, and wealthtech news

Access to Podcasts, with industry insiders along with annotated transcripts

Full Access to the Fintech Blueprint Archive, covering consumer fintech, institutional fintech, crypto/blockchain, artificial intelligence, and AR/VR

Read our Disclaimer here — this newsletter does not provide investment advice and represents solely the views and opinions of FINTECH BLUEPRINT LTD.

Want to discuss? Stop by our Discord and reach out here with questions

![The Power of Mortgage Pre-Approval [INFOGRAPHIC] | Keeping Current Matters The Power of Mortgage Pre-Approval [INFOGRAPHIC] | Keeping Current Matters](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!rdKa!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F05368f8a-ab8b-4524-b03b-2bfef441ce99_1301x1939.png)

Share this post