Long Take: Is Goldman or Walmart the best place to build a neobank?

Will Walmart's 250 million weekly visits convert into their BNPL app One?

Gm Fintech Architects —

Today we are diving into the following topics:

Summary: In this article, we discuss Walmart's neobank, One, which has begun offering buy now, pay later (BNPL) services, challenging Affirm's dominance in Walmart stores. With a strategy based on its financial partnership with Coastal Community Bank, One leverages Walmart's massive distribution network, evidenced by 250 million weekly store visits. We also explore the broader context of commerce overshadowing finance, looking at other commerce giants like Alibaba and eBay, and highlighting how these platforms have historically transformed commercial success into fintech opportunities. Lastly, we examine the ongoing shift where digital platforms could potentially dominate the financial landscape, overshadowing traditional banks and physical commerce.

Topics: Walmart, One, Affirm, Ribbit Capital, Coastal Community Bank, Cash App, Chime, Goldman Sachs, Marcus, Alibaba, AliPay, eBay, PayPal, Amazon, JP Morgan, Visa, American Express, Wells Fargo, HSBC, Apple, Google

If you got value from this article, let us know your thoughts! To support this writing and access our full archive of newsletters, analyses, and guides to building in Fintech & DeFi, subscribe below (if you haven’t yet).

Long Take

Bank of One

The catalyst for today’s note is the news about Walmart promoting its neobank, One, over partners like Affirm. Some great reporting on the topic was published here.

One is offering buy now, pay later (BNPL) loans for big-ticket items at several Walmart locations, likely being deployed across the 4,600 store footprint in the US. This puts it into direct competition with Affirm, the current BNPL leader at Walmart since 2019, for items like electronics and automotive accessories at an interest rate between 10% to 36%, with both services available for purchases starting around $100.

Since its inception in 2021, One has built several financial products, including a debit account introduced in 2022. Called by some as the potential "Bank of Walmart," this move aligns with Walmart’s historical attempts to enter banking, now realized through a joint venture with Ribbit Capital. One is not licensed, and relies on Coastal Community Bank for its debit and loan services, signaling a BaaS strategy that sidesteps earlier regulatory challenges faced by Walmart in directly entering the banking sector, such as their doomed 2006 bid to pursue an Industrial Loan Company.

One’s expansion also positions it as a player against fintechs like Cash App and Chime, which currently dominate the account growth among Walmart’s core demographic. With incentives like 3% cashback on Walmart purchases and a savings account offering a 5% annual interest rate, One will try to integrate more deeply into the financial lives of Walmart’s customers.

But look, the real news here isn’t the feature set of a neobank — that has been invented and delivered by numerous startups and banks alike. Whether your 3% cash-back ends at $50, or whether the APY is higher or lower than Chime, isn’t going to make or break the strategic case.

Much more interesting is the question of where an asset like this should sit, and what is upstream and downstream in the value chain.

The Choice Between Finance and Commerce

Case in point — the build of One has been led by Omer Ismail, who previously ran the digital banking efforts at Goldman Sachs, including the creation and integration of various services into Marcus (RIP).

From a fintech product and user adoption perspective, Marcus — from its lending arm, to its deposit gathering, to the various concepts around wealth management — was a success. But from a Goldman Sachs P&L perspective, B2C digital finance products for retail customers were a mistake. The digital transformation effort was mostly shut down after over $4B had been spent putting it together, stripped for parts between wealth management and technology services.

Intuitively, one would think that building a neobank at Goldman Sachs, with all the deep financial expertise of the firm, a century of experience, and every financial product on the shelf would be much easier than trying to skin a new brand on top of Coastal Community Bank from scratch and marry it to Walmart.

Why? Why? Why?

The answer comes back to distribution and manufacturing.

Commerce and finance are two networks that are intimately connected. Commerce is the expression of economic exchange, and finance is the rails upon which that exchange is transacted, and thereafter where the value is settled and stored. Most people — you know normal people who do not read a fintech newsletter — participate in commerce and know very little about finance. We have discussed this before at length below.

People *like* buying stuff. They like food, fashion, culture, cars, computers, media and entertainment. And at worst, everyone has basic needs that are met through commerce. When it comes to bank accounts and credit card rewards programs, those are quite a bit lower down the list of pleasures for the average consumer.

So, when we are thinking about addressable markets, we should consider not just the number of people that could be potential customers, but the amount of time and attention they spend on particular products. With that context, here are the numbers of times that people shop at Walmart per week —

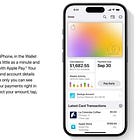

That’s right, Walmart sees 250 million weekly store visits. If the average shopper goes to Walmart somewhere between every 1 to 5 days, that’s 50 to 250 million people per week. Putting aside eCommerce and Amazon’s 300 million active users, we can see that the distribution channel is enormous. Walmart has 13 billion opportunities per year to convert customers into a financial product, all in the process of an economic commercial transaction (i.e., get BNPL from our neobank when you pay over $100).

In this case, Commerce > Finance.

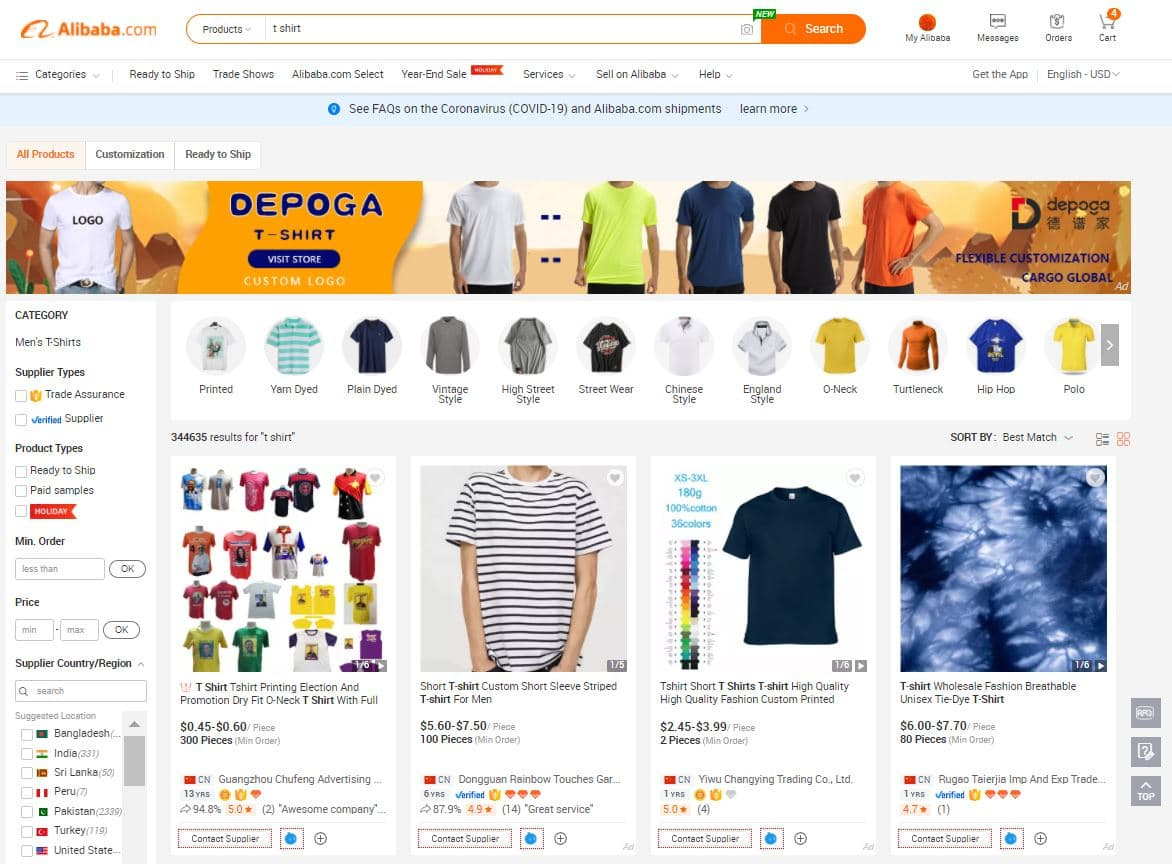

You might remember some other players, like Alibaba or Ebay, that started with an enormous commercial engine and ended up developing a fintech powerhouse. Their gross merchandise value flows converted into financial product adoption.

Ant Financial was, at one point, going to be the largest IPO of $35B at a $300B valuation — reflecting its scale of 1.3 billion users, 80 million merchants, and revenues of about $15 billion. Alibaba, the commerce platform that AliPay first supported, trades at around $1.4T these days. Even at this enormous scale, the fintech was a feature within the larger ocean of commerce.

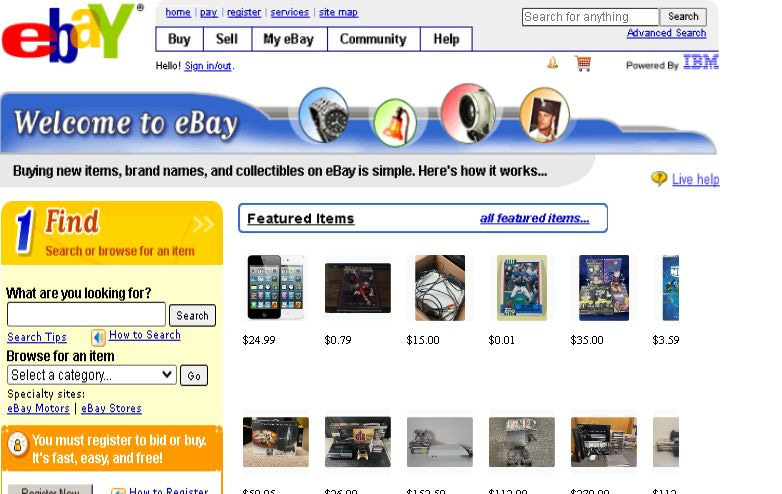

The same story can be told of eBay and PayPal, which we have previously explored here.

Today, eBay is worth $25B and PayPal about $70B, down from $200B+ during Covid. The fintech got its start by boostrapping off the eCommerce enabled by eBay in the early days, but went on to surpass it over time. We attribute this to a failure of execution on eBay’s part, missing the opportunity to become the Walmart of the Internet — an opportunity that Amazon seized admirably, now boasting a $1.9T market capitalization.

PayPal, along with every other payment method that Amazon enables, is a small financial feature in the larger offering that is a true marketplace. Even JP Morgan ($550B), Visa ($530B), and Goldman Sachs ($140B) barely add up to half of Amazon’s value.

The Role of Banks and Big Tech

Let’s invert the picture, and now look at a venue where finance is the top of the funnel and commerce is the adjacent product.

What comes to mind are the credit card and travel rewards programs, which allow people to cash in their rewards points across multiple retailers and airlines. One, the Walmart neobank, focuses its rewards on Walmart shopping — probably where most of the target demographic is already.

If you are a financial provider, like the medium-sized American Express, even if you aggregate multiple commerce destinations, you are unlikely to move real merchandise value. See here for the market size.

At a global $10B revenue pool, the entire loyalty market should capitalize to something like $100B in enterprise value.

Finance < Commerce.

The role of banks and fintechs is to embed themselves as a feature within real life, not the other way around.

One last noteworthy point is to separate out the threat that banks face from (1) Big Tech from (2) the one they face from the likes of Walmart. Of course, these can be mixed, but let’s try to draw out a distinction. The fear that banks had of technology is that Big Tech would beat them on the business model — that Apple and Google are far more efficient than, say, Wells Fargo and HSBC — and therefore would outcompete them on making and selling financial products. This is the same as a fear of fintechs, who are leaner, more automated financial firms, but expanded to Internet scale.

This is and was the wrong fear. Apple, Amazon, and Google all touch finance, but they do not want to manufacture financial products.

This was proven out by the generally disastrous Google attempt at expanding Google Pay into something resembling a personal financial management platform crossed with Venmo.

However, there is a thing that Big Tech can do that is more profound and dangerous. And that is to control the shelf-space for finance partners within digital commerce — whether that is eCommerce or proximity payments or within their social networks and metaverse games. For a clear example, see Goldman Sachs trying to exit its relationships with Apple or GM. Whereas Walmart, as a retailer, controls physical commerce within its stores, the digital attention footprints mediate what digital financial networks can access their customers.

And over here, we think Digital > Physical in the long run.

Postscript

Read our Disclaimer here — this newsletter does not provide investment advice

Another friendly reminder to share this post so that others can learn: