Hi Fintech Architects,

In this episode, Lex interviews Avlok Kohli - the CEO of AngelList, about the company's significant evolution. Initially a platform for startups to connect with venture capitalists, AngelList has transformed into a comprehensive fintech entity encompassing private equity and cryptocurrency. Avlok discusses the strategic pivots, including the introduction of syndicates and rolling funds, that have redefined the company's business model. The episode also explores the broader implications of crowdfunding and the unique challenges in the crypto space, offering a deep dive into AngelList's impact on the financial services industry.

Notable discussion points:

AngelList’s Second Founding: Reinvention as a Fintech Platform

Since 2019, AngelList has transformed from a mixed-use startup platform into a focused fintech infrastructure business for fund managers. Avlok Kohli spun out the syndicates arm and built a scalable product offering that includes SPVs, venture funds, and innovative structures like Rolling Funds and Roll Up Vehicles. This pivot catalyzed explosive growth—from ~$1B in AUM in 2019 to $171B+ today—by enabling fund creation and deployment at scale.

Product Innovation as a Strategic Advantage

Instead of competing with well-capitalized incumbents like Carta on sales and marketing, AngelList focused on building category-defining products. The launch of Rolling Funds—allowing fund managers to raise publicly and continuously—was a breakout moment. It created viral word-of-mouth growth and redefined how emerging fund managers could access capital, illustrating the principle: “You can’t win by playing someone else’s game.”

AI and the Future of Private Markets Infrastructure

AngelList is embedding AI across three strategic layers:

Back-office automation, replacing manual workflows

Customer service enhancement, enabling agents to respond to LPs with real-time data

Data reasoning products, like Fin, which analyzes anonymized fund and secondary data to deliver actionable private market insights

This positions AngelList not only as an admin platform but as a data intelligence layer over the private capital markets.

For those that want to subscribe to the podcast in your app of choice, you can now find us at Apple, Spotify, or on RSS.

Background

Before becoming CEO of AngelList, Avlok Kohli was a serial entrepreneur and software engineer with a background in software engineering from the University of Waterloo. He founded and successfully exited multiple startups, including Fastbite, a food delivery service acquired by Square in 2015, and Fairy, a home cleaning platform acquired by Postmates in 2019.

Avlok began his career in engineering roles at companies like Zvents and Doximity after moving to San Francisco during the 2008 financial crisis. His ventures attracted the attention of Naval Ravikant, leading to his appointment as CEO of AngelList in 2019, where he spearheaded its transformation into a leading fintech infrastructure platform for venture capital.

👑Related coverage👑

Topics: Fintech, Web3, Venture, VC, Venture capital, private markets, fundraising, crowdfunding, crypto, web3, AI, Angellist, Coinlist, Carta, Gumroad

Timestamps

1’09: AngelList Reimagined: How Avlok Kohli Transformed a Startup Directory into a Fintech Powerhouse

6’43: Syndicates vs. Crowdfunding: Solving the Signal Problem in Startup Investing

11’43: From Community to Capital: Rebuilding AngelList Through Business Model Reinvention and Rolling Fund Innovation

16’49: Playing a Different Game: How AngelList Scaled by Redefining the Category Through Product Innovation

21’59: Creating the Category: How Rolling Funds Sparked a Movement and Redefined Venture Fundraising

28’51: From $1 Billion to $125 Billion: How AngelList Scaled by Saying No Before Saying Yes

32’56: The Liquidity Mirage: Why Private Market Access Remains Elusive for Most Investors

37’57: AI Meets Private Markets: Automating Back Offices, Enhancing Customer Touchpoints, and Powering Intelligent Fund Infrastructure

42’26: The channels used to connect with Avlok & learn more about Angellist

Illustrated Transcript

Lex Sokolin:

Hi everybody, and welcome to today's podcast. I'm thrilled to have with us our black colleague who is the CEO of AngelList. I'm guessing that everyone in the audience knows of AngelList, but we're going to explore what AngelList is today and the transformation of the company over the last five years. With that, I'm really excited to have Avalon on the show.

Avlok Kohli:

Great. Thanks for having me. Excited to be here.

Lex Sokolin:

So let's start with the easiest and the hardest question. What is AngelList?

Avlok Kohli:

It depends on the year that you've heard or use angels. So today, AngelList is the go-to fintech platform for guys that are looking to raise or scale their fund.

We have had been focused on venture, but now we are in private equity, crypto and all of that. So that's in a nutshell, what AngelList does today. The history of AngelList actually goes all the way back to 2010, where it really started off as a place for startups to come raise capital from VCs. And that was the original idea. And through the years went through several pivots. And, you know, from 2010 to 2019, there were several pivots and explorations. One was actually a syndicate platform that was Basically the ability for someone to create an SPV and raise from multiple investors. There was a talent platform, which is what most people actually knew of AngelList back in, you know, before 2019 and then had also acquired Product Hunt as well. So, they're kind of the three core pillars, if you will, evangelists from 2010 leading up to 2019. In 2019, I came in and I actually took the syndicate part of the platform. It was a small part of the platform and actually spun it out because it had the makings of a of a potential fintech.

And think of that as a new founding moment for the company. And we ended up scaling that piece out. And so, we've gone from syndicates to small venture funds to large venture funds to we invented whole new products like rolling funds and roll up vehicles. And we just kept innovating. And that actually was the new founding moment for AngelList. And we grew that from 2019 to where it is today and the other parts of the platform the talent, business and product hunt were separated to talent. The talent business is now called Well Found and then Product Hunt is still called Product Hunt, but it's run separately with a separate CEO.

Lex Sokolin:

That is a hidden story that I think a lot of people don't know. My personal memory of AngelList is it's a list of angels on the internet. I think Naval founded it in kind of early web two days. I remember for a company I founded called Nest Egg, which was an early robo-advisor. I tried to raise some money on it and, you know, like I spent a week polishing PowerPoints and putting in different things into the interface.

And then kind of the magic trick was that once you hit publish, Naval would personally take that information and send it to a bunch of people in the network. And I remember that email in my inbox. It was like such a surprise, you know, that you had that personal, handcrafted attention. Why wasn't that enough? That's a great product. I'm sure that community had grown quite a bit. Was there anything in that model that didn't click, or why? Do you think the company needed to keep searching for these different ideas?

Avlok Kohli:

So it turns out when you announce the world that you can come to a place like AngelList to raise capital in the beginning, it's great. You get a lot of very high-quality founders, high quality startups. But when it works, which it did. And, you know, famously, Uber actually raised their first round through AngelList. When it works, you have everyone that shows up. And so, the ability for someone like Naval or anybody who's the other co-founder to hand review everything, handcraft everything and send it out and really pay attention to every single startup coming in, it just goes down.

There's just not enough attention, not enough time in that day. And when everyone shows up, the signal to noise ratio actually gets lopsided. What that means is you had a lot of startups that showed up that weren't high quality and couldn't really raise that capital, but it just inundated all the entire platform. So, it just didn't scale, right. So that concept from one side of the market actually worked extremely well. Startups loved it. They showed up. But from the other side it wasn't. The signal went down over time, and it was a lot harder to parse out which company is worth paying attention to versus not. Now, one way to address that would be a Y-Combinator style model, where you literally interview every single or you interview. Most of the startups that apply, and then you let in a small percentage. But that wasn't the core DNA or the core model of AngelList. It was really focused on building software to scale a product. And so, from there, what ended up happening was the syndicate model was born.

It was, well, if the people in the company can't parse the signal, can't review every single startup, what they can do is they can actually have a syndicate lead. So, someone who is going to put their own capital in an angel investor and they'll effectively say, hey, I'm tying my capital to this company. Now you can come behind me. And so that was a solution to actually address the signal to noise problem as the user base started scaling.

Lex Sokolin:

So I think this is actually endemic to a lot of crowdfunding. Not that AngelList is straight crowdfunding, but you do have this lemons problem. You know, in early crowdfunding platforms, you know, the more projects you get, you start getting lower and lower quality because there's only a small percentage of the long tail. That's good. And then similarly, in coffee trading platforms and other comparison, you have the same issue. So, you think that syndicates is a good way to address it.

Avlok Kohli:

Yeah. So syndicates ended up being a really good way to address that for the early-stage startups.

And this was again, this was in a different time when syndicate was originally launched, which I think was actually around 2016 time. And the reason it ended up being a good way to address it is it forced someone to put skin in the game. Right? They had to put capital behind something. And when you're forced to put your own capital behind something, then other people are more likely to listen to you. But that's just one sort of signal. There's another sort of signal within syndicates, which is who is the lead investor. Like, is there a larger venture firm also coming into the deal, leading that deal? Now that's not always there. But when there is, when it is there, that's another form of signal. And so, you can think of it as hierarchies of signal that other LPs, people who want to invest in that deal. She listened to. So one is, of course, the syndicate leader who's going to be putting their own capital in. And then the other one is who the lead VC is.

And they're going to be looking at that as well. So, think of it as a hierarchy of needs as a way to solve the whole signal to noise problem. And I don't follow any of the other platforms super closely. But if I were to just unpack the crowdfunding, which is a completely different class, it's actually even from a regulatory structure, it's very different and how it works. The problem with crowdfunding is there is no signal, right? You can have anyone that goes there, goes to raise capital. And so, it suffers from the whole signal to noise problem. And there is no skin in the game there. You don't quite know who's actually putting significant skin in the game. So, when you're raising capital from a crowd, there is you don't have the same type of signal that you have when you're in a traditional VC, right. Which AngelList plays in.

Lex Sokolin:

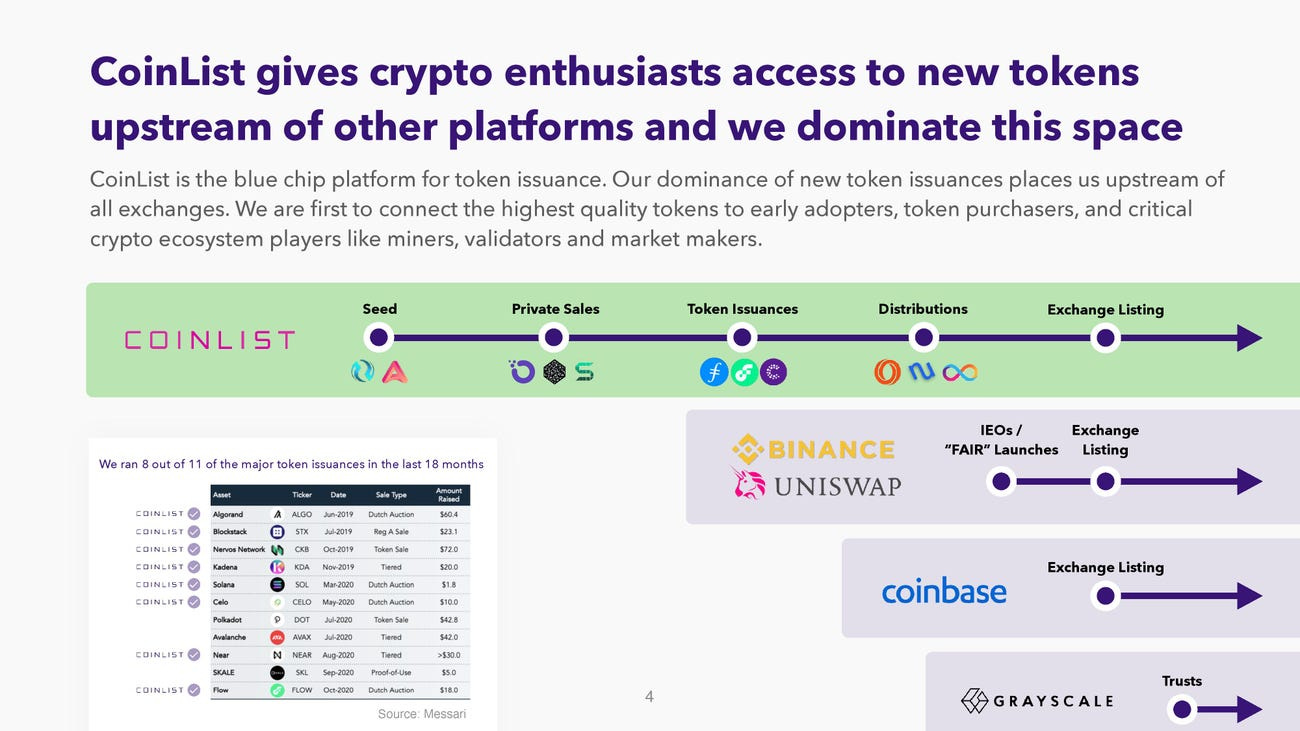

It's interesting to go on this tangent as well, because Coinlist was, I think, a spinout of AngelList, if I'm right. And they definitely went all in the crowdfunding direction and into crypto, you know, which combines sort of as retail, a broad access as possible. But you think that the kind of the lemons problem is too strong or like it doesn't scale into quality.

Avlok Kohli:

So crypto is is a little bit of a different asset class in the way the projects come together, since it isn't just about the security. Sometimes in crypto it's about you want to create the community because you have a particular token for your project that behaves differently from, let's say, securities, which shares in your company and with crypto and crowdfunding the need sometimes on both sides of the equation, the token issuer as well as the receiver, they're doing it for something beyond just issuing securities and engaging in that way. And so there, you'd still suffer from the same issue. It's not that you don't. And you can kind of see this, right. You can actually see it in all the tokens are getting that are out there. And you see some small percentage actually get listed by Coinbase and by the exchanges. Now with Coinlist. Coinlist does have a quality bar. So, they do review and evaluate which ones to bring on, even for the crowdfunding side.

But I would say crypto relative to venture investments, it does behave differently. And so, the back story here with why Coinlist ended up being a spinout. This was before 2019 is in the original crypto boom. What happened was there's a lot of activity and excitement to come into these crypto projects. But the regulatory framework wasn't very clear back then. And the core venture platform, which was syndicates at the time within AngelList, was pretty clear what the regulatory structure is, very clear guidance from the SEC. But with crypto, there was no clear guidance. And so, it was just an unknown, risky proposition of, hey, we don't quite know where the regulatory framework will land. And so, it made sense for Coinlist to separate and actually be its own entity. T, so it can actually go down its own path because it was it could have ended up down a very different regulatory structure. That doesn't look like the venture. You know, the era, except it's called the exempt reporting advisor structure. So there was a regulatory reason why it made sense to separate the two, the two entities.

Lex Sokolin:

You know that original core of startups, product hunt jobs for startup employees, you know, is like there's a lot of demand from that community, but it wasn't as commercial or as monetizable. And so, you came in in 2019 and said, we're going to build sort of a more robust business and focus more on the investor side. What did that require? Can you walk us through maybe just even like the decisioning to assess the strategy at the time? And then once we do that, I'd love to understand the transformation across the different business functions. But first, just, you know, it is a rebirth of the idea and talk us through that.

Avlok Kohli:

When Naval and I originally discussed me stepping in. You know, my experience prior to that was I started three companies that sold to them, and one of them was The Square. And so, I was at Square for almost three years and actually saw their transition from a payments angle into the behemoth that they are today. And one takeaway I had from the Square experience was when you're in the payments flow, you have all sorts of adjacent opportunities that you can actually expand to.

And Jack had this really pithy way of compressing it, which was, you know, Square wanted to be at the beginning and end of every transaction because you can then monetize everything in between. And so that concept I carried with me as Naval and I were looking at AngelList. And the thing that was very interesting to me about the syndicate business was it was an all-in-one proposition where someone could come in, spin up an SPV raise from all these LPs. We were in the money flow and then we deploy it into the company. And it was a much, much smaller business back then. But the fact that it was just working and the fact that people were consistently using it meant there was something to work off of and something to scale off of. The other piece was it was just unique, like there's literally no other, no other business, no other platform that did this. And you also want to you want to find that when you're building products, you always want to focus on something that's differentiated, something that if you didn't exist in the world, it wouldn't exist in the world, right? That's super, super important.

I think a lot of founders missed this one piece. So, if you don't exist in the world, this product wouldn't exist. You really want to focus on that. And the thing that was pretty clear when we were looking at it was there was something here. The problem was the business model was basically all carry, and it was carried interest. So, if you would raise an SPV and you closed LPs into it, we would charge carry on your LPs or on Angel LPs who would be LPs that we've actually brought to the table. The issue with that model is when you have your own LPs, it feels off to charge carry. So that's problem number one. Problem number two is carry is future profits right. It's unknown. Future profits. You don't quite know where it's going to go. It can be a lot, or it can be a little. But when you need to invest in and build a fintech platform, you need to hire, and you need to scale the team, and you need to be able to rely on recurring cash flows.

So those two things were clear problems that we had to change, we had to solve. And that was the first step, was actually do a reset on the business model. And just overall how we think about, you know, scaling this product. Once we did that, the next step was to actually look at where do we take this roadmap. Right. It had syndicates in it, and we just started working on these like small microphones, and I'm talking like half $1 million microphones, $1 million microphones. And to me, it was pretty clear that we had a foothold in the small SPV market, and we needed to scale the SPV size that we need to get into venture funds. And then more importantly, we just had to innovate. We had to actually create a whole new product. And it was really, really good about this and is always, you know, thinking and looking around the corner of what could be like, what is something that just doesn't exist in the world today. And we ended up tackling rolling funds.

That was actually our first big innovation on the fund model. And no one really innovates on the fund model, by the way. It's actually quite rare, but we ended up launching rolling funds, and that was actually the key demarcation between what we had before and where we are today. And the reason is because rolling funds. Actually, put Angeles on the map for fund management. Everyone knew us for SPVs and syndicates, but they didn't know us for venture funds or really just fund management. But rolling funds put us on the map for fund management, and we went through a massive growth spurt on the back of that, on our on our like fund, on our venture fund and rolling fund business. And so that ended up being sort of the key changes, right. First, it was the business model changes and really looking at what, you know, making a decision on what type of underlying business you want to build. And then the second one was getting back to product innovation. And that product innovation drove a huge amount of word of mouth for us, which grew the entire business.

Lex Sokolin:

What did you need to transform in terms of the teams, you know, marketing, technology, sales? What was the culture and working environment like in AngelList prior, and then to build it into, you know, what feels like a far more institutional business. What is it that you had to do from an organization perspective?

Avlok Kohli:

So it's interesting, if we go back to 2019, I remember Naval and I had a meeting, and the first thing I always do is I sort of look at the state of the business, looking at customer activity, customer churn, and sort of looked at it and went, okay, we need to solve this problem. We have to grow this business. And the normal way of doing it is great. Let's go higher sales, let's go higher marketing and let's, you know, beef up the team. The problem with that is when you're competing with others who have a much larger war chest than us at the time, you can't win playing someone else's game, right? You can't win. Going toe-to-toe on an area that someone else is better than you at. So, you know, at that time we didn't really, we weren't really strong at Net sales, and we didn't really have much marketing within the company.

Lex Sokolin:

Sorry to pause you, but I want to meditate on this kind of statement. You can't win at something that somebody else is better than you at. Can you just expand on that and then, you know, where do you draw that from?

Avlok Kohli:

The way to think about this is if you're competing against another company who is really good at sales, has a deeper war chest than you to continue to invest in sales and deeper war chest, and you can continue to invest in marketing. If you go head-to-head with them at that moment in time, you will lose unless you have some unique edge. And the way that it's the same concept as you know, you have a product you're trying to bring to market. If you are the second, third and fourth product and market, and you are slightly better than all of the than that first product that has a foothold, you won't win because it doesn't deserve the attention, doesn't capture the attention of any customer that you're trying to bring in, because in their minds, someone's already won that category, right? And trying to go head-to-head to convince someone of, oh no, we are better, but you're only slightly better.

You're not going to win that game. Now, if the category is completely open, it's different. But most categories that people look to step in are actually owned by someone. And if you're going to go compete head-to-head. The only way to do so is your product has to be significantly better, or you just change the category entirely, meaning you carve out a different product category. And so that that concept really comes from that insight, which is you can't win by playing someone else's game. You have to chart your own path. And what that really meant for us was we had to innovate. There was just no other way to do it. We could build a traditional venture fund product, which we did, and we had, but trying to go toe to toe with other fund management platforms back then, who already had a foothold, were already known for it, already had a brand. Everyone thought of those as the go to folks for that product category, so we just could not compete on that playing field no matter how much money we spent.

Which by the way, we didn't have much money back then, right in the bank. We weren't going to be we weren't going to win that game. And so, the focus was actually on product innovation, which was really where we ended up focusing all of our energy, which is how rolling funds actually came about. It was a true product innovation. It owned the product category and at the same time created a whole new marketing moment for AngelList. That was basically self-fulfilling. Like what would happen is customers would launch the rolling funds, they would go on Twitter. They'll talk about it because we designed the product in that way, and they will talk about it. And it would just create all of these natural growth loop marketing moments for us, which then had a spillover effect into the rest of the business, into our traditional venture fund product and our syndicate product.

Lex Sokolin:

You had this advantage in terms of startup awareness and supply and sort of like the early-stage ecosystem. You also had the other side of it, which was a syndicates and small venture funds who were using the platform.

And so once you were leaning into those, you had to figure out the dimension on which to compete. And you can't compete on the dimension in which others are already strong. So, you know, you're trying to play a multi-dimensional game here, you know, and I assume that the folks you're deciding to take on really in that moment is Carta, right, who's kind of sitting on top of private markets. Carta is a good competitor. They're young as well. But they've also explored different areas of markets. Came in to try to do secondaries left secondaries. You know, they're also evolving sort of at the same time. And the way that you're choosing to take them on is through this rolling fund product, which is difficult to do, difficult to service. How big was that market for people who wanted to build rolling funds, like, was there already pent-up demand, or did you have to create it as well?

Avlok Kohli:

No, this is actually one thing I've learned from Naval is products that are truly new, and no one's done before.

There's no one that's coming to you saying, oh, I want to use this product. When Uber was developed, I don't think anyone was even thinking at the time, oh, it would be great if I could just tap the button and have a car come to me. That's the case with any truly new product. There is no pent-up demand. You can't go to a customer and ask them, hey, tell me what you want. I'll just go build it. You don't get breakthrough products that way. This is a, you know, the classic quip. If you ask people what they wanted, they would say a faster horse. And so, there was no pent-up demand. And actually, when we first launched it, I remember it was actually right before Covid, and I think it was a fortune article where we launched Rolling funds. And I remember I was like, oh, this is a great product. We launched it and I was just waiting beside the email to see, all right, we're just going to see this huge amount of demand coming in.

And it was just crickets. It was like, oh wow. No one no one's really, you know, banging on the door. And then Covid hit, you know. So it was like a, I would say a couple of months, just like readjusting to what's happening in the world. But once we sort of settled into this new reality of Covid, they've all and I looked at it and we looked at it and said, okay, this product is clearly good. It clearly solves a problem. We need to just give it an initial push. And the way we ended up doing that and all credit involved in this one for this insight was going to specific GPS that are within the Angela's network and saying, hey, why don't you start your rolling fund, and we'll help you raise for that rolling fund. And specifically, Naval would do a session with them with our top LP. So, we actually organized a very exclusive group of top LPs for an if I remember it was actually a weekly session or biweekly session to put a GP in front of them of all would talk about them.

Why? Why they think this is a great GP and they would have a rolling fund and by the end of the call we would actually send out a link and LPs could come in. So that actually created the movement, right? It started a movement. By the way, I think every great product is a movement. Every different every new product is a movement. It's an opinion of how the world should work. And there's this new book by Mike Maples that I think actually captures the whole essence extremely well. I think it's called Path Breakers (Pattern Breakers). And so, we went from session to session, GP to GP helped them raise capital. And one of them was Sahil from Gumroad. He launched his rolling fund. And we did this session. And you know, a few weeks later he comes to us and says, hey, I'm actually going to be launching it publicly on Twitter. And he said, great. That's awesome. Happy to support you however you want. He had some questions. And, you know, we expected the day to come.

And he was going to launch it on Twitter. And it would be, you know, it would be just like any other launch. Great. It's exciting. A lot of LPs coming in. But the way he launched it, he actually coordinated his launch, and I believe it was a TechCrunch post. And there was one other thing, and I think it was sort of just the perfect launch for the for that moment in time where everyone was online and it was covered across multiple touchpoints, and the product itself was salacious enough. And okay, what do I mean by salacious? One, it's an actual innovation on how a fund could work. Number two, is it enabled public fundraising. And that is antithetical to the way fundraising is typically done for venture funds. Venture funds typically fundraise through a very it's called 5 or 6b where you can't talk about it publicly. You can only really talk about it privately. Right. But there was actually a new rule 560, which allowed for public fundraising that a lot of people didn't know about.

In fact, a lot of lawyers didn't know about it. And that became the salacious part where you had people engaging on Twitter effectively saying that what he was doing was illegal and AngelList doesn't know what it's doing. And I remember I was actually on Twitter actively responding to people and citing the literal rule that actually allows for this. And one misunderstood fact about AngelList is, you know, some folks, it doesn't happen as much anymore because we're a lot more institutional and a lot more scaled up. But back then, the one misunderstood fact about AngelList was we were just a bunch of rule breakers, and we didn't really have respect for, you know, the rules and the law and everything. What they didn't know is and folks still don't deeply appreciate is we are actually very active on the SEC policy side and always happened actually in the first literally a few months of me joining. I actually went to Washington to the SEC to weigh in on a bunch of policy decisions, but folks don't know that, right? And this has actually been a deep history of AngelList.

In fact, Naval was part of the volunteer. We were part of actually getting the Jobs Act passed in 2012. And then we also have, you know, we also engage pretty regularly with Washington on the legislation side as well. And so that one piece, really the distinction between 5 or 6B and 5 or 6C, which is really private funders and public fundraising created that salacious moment in addition to sales marketing chops, that it sort of created this zeitgeisty moment for the company, which then pulled us. It literally pulled us forward. We had like a waiting list. We had people trying to use the product, trying to get in. Folks would actually be sending my friends messages, trying to get access to me to try and get in, to try and use the product. Yeah. It was. I mean, when I say product market, it was like it was probably the definition of it. It was so strong. We're like, we have to put a wait list.

Like it was just way too intense because we were still a tiny team back then, we hadn't even adjusted to the whole thing. And so that ended up being that one zeitgeist moment. But actually we literally traced it back to Sahil’s Rolling Fund launch.

Lex Sokolin:

If you kind of draw that line forward. Right. I think now there's somewhere around 125 billion of assets that has been put together with the platform. Where were you in the beginning, like around that pivot? And how did that growth come?

Avlok Kohli:

Oh yeah, I think around then we must have been maybe like a billion. I'd have to confirm that. I remember the first goal we set when I stepped in. It felt so ambitious. And we had this mission, actually, when I first stepped in. We'd set it in place, and we were like, wow, this. This will be an ambitious goal. And we basically ended up crushing it within a year and a half. And we never look back. In fact, actually, I think the company Was a little lost, actually, for a few months because you need teams.

Need like an ambitious goal. Right. And I remember we just crushed that goal, and we were almost a little bit lost. We're like, well, shit. That that felt very big. Now we have to go even bigger. And while we're setting it, the team was like, well, what do we what do we focus on? Like, what's the big ambitious goal we focus on? But yeah, we must have been back then like maybe a billion in assets. And you know what? What ends up happening is as you grow, as you scale. Because actually the one misunderstood, another misunderstood. Angela says, as we've taken on customers, we've very selectively and purposefully started with the smaller SPV, smaller funds by design. We used to have funds that came to us that were 100 million, 150 million. Half a billion. And we would say no. And people would be shocked, like, wait, why are you saying no? Well, we said no because we weren't ready to take them on, because our approach to it is categorically different than what other platforms do.

And so, we would, step by step, bit by bit, take on larger and larger funds. But now as we're taking on larger funds, you just see this huge growth because we're more than comfortable now taking on the ultra large funds in fact. You know, we actually power scout funds for some of the top venture firms. And by top, I mean like literally top five venture firms in the world because our infrastructure is very sophisticated. We're now able to serve them. But we would not have been able to serve them even three years ago. Actually, it would have been very tough for us.

Lex Sokolin:

That's an amazing transformation journey. I mean, that's absolutely huge scale that you've been able to get to. I want to ask you about more broadly the private markets. Right. Because now you're sitting and doing fund administration and sort of all of these sorts of gears of private markets investing. And one of the ideas is that we as investors or just in the media, see, come up over and over again.

I guess there's two ideas. One is creating liquidity for private equity. You know, sort of the everybody's tried it from the crowdfunding platforms way, way back to, you know, some of your competitors to the crypto people have said, you know, we'll give liquidity to private equity. And it seems even though there are platforms that facilitate this, it's still seems really hard far away. And it's not really what regular people do is that they don't get exposure to this asset class. And then the other story that's also at this point, a 15-year-old story is, you know, companies are going public at 50 billion after all of the original capital gains are gone. And so, you know, you're not going to get Amazon, you're not going to get Google. Right. Like Figure without any revenue, real revenue or distribution raised at a $40 billion valuation, OpenAI is 300 billion. Anthropic is again like 40 or 50 billion. So, you've got this huge value leakage out of the public markets.

The public markets are just giant asset management robot machines. So, there's sort of like this mythical Valhalla of if only private equity could be liquid in everyone's portfolios. And at the same time, it is so profoundly difficult from a regulatory perspective as well as from just a market structure perspective. Given your current vantage point, how do you look at this problem? Like what are ways in which it can be quote unquote solved, and what are the potential pathways going forward?

Avlok Kohli:

There's two different types of assets we're talking about here. I think there's a venture a non-venture. And I know it gets bucketed into private equity. But private equity has way more than just venture. I would say if we're talking about venture it is true that companies are taking longer to go public. It is true that, you know, those gains for those companies aren't being captured by the retail class, by the non-accredited. And. And that's definitely a shame, you know. And again, I actually understand all of the incentives to not go public.

I think the reality was it has got harder and harder to go public. Also just setting the bar has changed from even two decades ago. You would actually have a class of investors in the public markets that would be comfortable with, you know, companies that don't have like a billion in revenue. But nowadays you sort of have this like minimum bar. You have to clear in order to even consider going public. Otherwise, you're just not given the time of day. You're not given the space to evolve the business. So, I think there's a question of risk appetite in the public markets. I actually have heard arguments on both sides. You go public, there is risk appetite as long as you execute. And versus the other side is, hey, you just need to give the company time to mature. Right. And I appreciate both sides of that argument. The reality is going public is a one-way door. And so, once you do it, it's very hard to reverse it. It's very hard to actually go private, which is, I think, what the underpinnings are for, why a lot of these companies are being cautious about when they decide to go public.

So that sort of like this broader commentary now in terms of liquidity in the private markets and how you provide more liquidity in the private markets. I think the vast majority of the volume is concentrated in the few companies that have the ability to go public soon. Right. Or there's a lot more known about that company to have the brand, because you have a lot of companies under the radar. They're doing extremely well, but they just don't have that brand yet. And the way I think about this is that company is actually being underwritten based on their probability that they're going to go public soon, because we're going to invest at the later stages. You are like your return horizon isn't the 10 to 15 years, which is what it is for early-stage venture. Your return horizon is more like two to 3 to 4 years because you're expecting this company to go public, and then you're going to return capital to your LPs, and then you'll go through the next cycle. And that isn't going to change. Right.

I actually don't think that dynamic will change. I don't think we'll all of a sudden see more liquidity to the earlier stage companies, because it is it's a question of risk. It's a question of return horizon. And it's a question of brain. Right. So, all of these things actually factor into it. So, you have a lot of the same dynamics that appear in the public market starting to creep into the late-stage private markets. And I don't think that will change now in terms of my broader view on liquidity within venture for, let's call it the non-accredited class. I think the best way to do that is actually through a, a fund. And the reason I think it's the best way to give the non-accredited investor class access to venture through a fund is you can then allow for risk of loss, right? You can invest in a broader set of startups, whether it's early stage, mid stage or late stage, you can absorb the loss, you can capture the upside, and it behaves a little bit more like the S&P 500, right? It's not exactly right, of course, because there's a lot of rebalancing that happens.

But you can at the very least get some resemblance of an index versus getting concentrated exposure to companies that actually do have high risk of going out of business or high risk of, you know, high risk of not returning what you expected of that of that company. And I think that's the best way for the non-accredited investor class to access and share. I'm not sure if we're going to see like more and more liquidity continuing to flow in. In fact, I mean, the big, you know, the big sort of narrative and news right now is there's not enough liquidity within the private markets. I don't know if that's going to change. I do think the only way for that to change is for these companies to go public, because it's a similar dynamic. A lot of capital is going to a few companies in the secondary markets. We're personally not seeing that trend change.

Lex Sokolin:

One thing you mentioned prior to the conversation was artificial intelligence, and how that's getting pulled into your products as well. Of course, a huge theme on the investment side, but I'm curious, especially in financial services and in sectors that are so clunky in terms of regulations, lawyering, workflow, you know, all this stuff. How are you seeing AI getting applied to. Clear that up.

Avlok Kohli:

Yeah. The way I think about AI, it's digital intelligence. And if a human can do it once, then the digital intelligence can replicate it forever. Right. And when it comes to finance and fintech. There is a surprising amount of back-office work that's there. And the back office work you can think of as a lot of playbooks that a large group of humans execute on, and that will ultimately just all get automated through AI, because you have a human that's applying a playbook that has to apply some judgment on something that they're looking at, well, where they AI, they can actually apply that judgment 24 over seven, and you can scale it up infinitely and it's a lot cheaper. So, I view AI is going to, at a minimum, look at all the back-office tasks and automate a large portion of it, and it'll force the humans to get pushed up the the creative ladder.

Right. It's hey, they can actually go do higher value work, more creative work versus the rope. You know, the execution work that's there today. So that's like one area. I think the second area is. Think of that as like the touchpoint between the customer and the company through like customer service. I think that's another obvious area where it will automate quite a bit of the customer touchpoints. So, for example, if I'm an LP emailing into AngelList asking about my K1, guess what? You can actually have an agent looks at it. It knows who the LPs LP is. It's connected to the underlying database. It can easily understand that question because English is the programming language now. It can take it, hold the K1, send it back to the LP, and that's it. You're done. You've actually automated that one touch point. That's another area. And then the third is, I would say in the customer facing product like a. Net new product that unlocks something that just wasn't possible before.

And so, you know, one example of this angel has just launched this product in beta called Fin, where we built a reasoning agent on private market data. So, we've aggregated, anonymized and AngelList data. We've also connected it to our customer's private fund data like their own fund. And we've partnered with a bunch of different service providers. So, for example, one of them is a provider to aggregate secondary data. Actually, they've actually aggregated from all the providers. So, I can ask questions like, you know, how much secondary volume was there for space in the last quarter. And I can get that answer. I can even get it right down to the studs and look at what was the actual, you know, buy, sell volume. What were the numbers? And it can allow people to very quickly get to a fair price for, you know, whether they're a buyer or seller. And that's another example of a how AI is actually going to impact fintech and finance overall. But I'm actually very excited about it, I think.

And we actually, at AngelList have initiatives on all three of these areas. I do think the one thing that will be really, really important is the error rate on finance and expectations of AI and finance will be very low, and you have to parse out where, like what sort of systems you're building, where the error rate has to basically be zero, and how do you do that. And so, we have some ideas on that. You know, there's a concept in accounting called maker Checker. You have one thing that does the thing. The other thing that checks the thing. And so, we have different ideas on how that's all going to come together. But yeah, we see AI impacting finance in a big way.

Lex Sokolin:

That's fascinating to get that unstructured data out in a way that that others can consume, and markets can consume. And I think that's actually quite valuable. And there's lots of examples of businesses that find data to be the magic thing that gets squeezed out of it. You know, even the exchanges, the large exchanges are primarily data businesses, once you get rid of all the fees.

Avlok Kohli:

That's exactly right.

Lex Sokolin:

Well, this has been a fascinating discussion. I've learned a ton about how AngelList has transformed. And you know, that journey is not easy. And basically starting a new company with assets of the old company and building a new culture and creating new goals and then fighting some pretty tough battles. If our listeners want to learn more about you or about AngelList, where should they go?

Avlok Kohli:

Yeah. So for me it’s x.com/avlok, and then for AngelList it would be x.com/angellist.

Lex Sokolin:

Fantastic. Thank you for joining me today.

Avlok Kohli:

Thank you for having me. This was great.

Postscript

Sponsor the Fintech Blueprint and reach over 200,000 professionals.

👉 Reach out here.Read our Disclaimer here — this newsletter does not provide investment advice

For access to all our premium content and archives, consider supporting us with a subscription.

Share this post