Hi Fintech Architects,

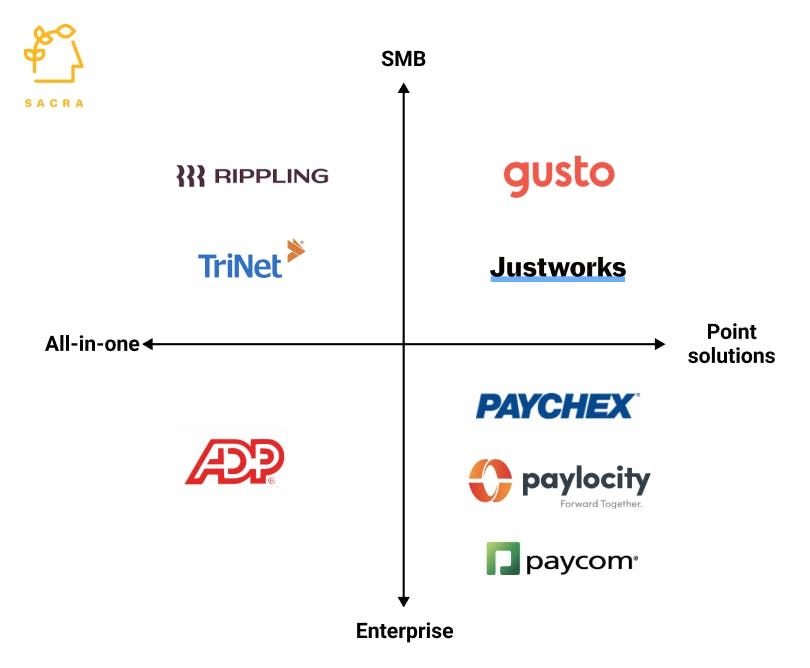

In this episode, Lex interviews Josh Reeves, co-founder of Gusto, a company specializing in payroll, HR, and benefits solutions for small businesses. Josh shares his journey from academia to entrepreneurship, highlighting the challenges and strategies involved in building Gusto. The discussion covers the evolution of technology from Web 2.0, the importance of understanding customer needs, and maintaining strong unit economics. Josh emphasizes Gusto's mission to simplify payroll and HR tasks for small businesses, aiming to improve their survival rates and overall efficiency. The episode underscores the significance of product quality and customer satisfaction in navigating industry competition.

Notable discussion points:

Solving Payroll as a Massive, Underserved SMB Pain Point

Reeves highlighted how in 2011, 40% of small businesses were fined annually due to manual payroll errors. Gusto addressed this pain using cloud and mobile tech, making payroll fast, accurate, and accessible—especially for non-experts.

Product Sequencing and the Power of a Payroll-Centric Ecosystem

Starting with payroll, Gusto built a sticky, horizontal product with strong retention. From there, they expanded into benefits, time tracking, and more—adding products based on customer pull and reinforcing their ecosystem.

Organizational Evolution: From Founder-Led to Functional and Matrixed

Gusto grew from 3 co-founders to 2,600+ employees by evolving from a hands-on team to a matrix structure. Reeves emphasized hiring leaders suited to each stage and giving small, focused teams autonomy to drive new product development.

For those that want to subscribe to the podcast in your app of choice, you can now find us at Apple, Spotify, or on RSS.

Background

Before founding Gusto in 2011 (originally named ZenPayroll), Reeves co-founded Unwrap, a platform that enabled users to create Facebook apps without coding knowledge. Unwrap gained significant traction, amassing 40 million users before its acquisition by Context Optional in 2010.

Reeves holds both bachelor's and master's degrees in Electrical Engineering from Stanford University. His academic focus on signal processing instilled in him a passion for simplifying complex systems—a philosophy he carried into his entrepreneurial ventures.

At Gusto, Reeves emphasizes a mission-driven approach, aiming to humanize workplace processes and empower employees. He believes in building a company culture that values introspection, continuous learning, and alignment with core values.

Beyond his role at Gusto, Reeves is an active angel investor, supporting early-stage companies like Flexport and Airtable.

👑Related coverage👑

Topics: Fintech, Gusto, Payroll, HR, Zazzle, SMB, CAC, Customer, Scaling, Growth, Web2.0

Timestamps

1’13: From PhD Dropouts to Payroll Pioneers: Joshua Reeves on Building Gusto and Solving Real Problems with Technology

4’21: The Web2 Reawakening: Democratizing Creation and Commerce Through the Internet

8’14: From Pen and Paper to the Cloud: Tackling Payroll Pain and Modernizing SMB Operations

11’15: Is Gusto a Fintech?: Ignoring Labels, Solving Problems, and Building for Small Business from Day One

16’07: Cracking the SMB Code: Building Scalable Products with Strong Unit Economics and Organic Growth

19’39: The Fundamentals of Scaling: Navigating CAC, LTV, and Retention in Subscription Businesses

22’49: Building Beyond Payroll: How Customer Demand and Smart Sequencing Shaped a Scalable Product Organization

27’16: Scaling with Intention: Evolving Leadership, Structure, and Talent from 10 to 2,600 People

33’00: Structuring for Scale: Balancing Autonomy, Focus, and Flexibility in a Multi-Product Organization

36’22: From Traction to Tenure: Scaling Impact, Navigating Competition, and Building for the Next Decade

41’12: The channels used to connect with Joshua & learn more about Gusto

Illustrated Transcript

Lex Sokolin:

Hi everybody, and welcome to today's conversation. We are very fortunate to have with us today, Josh Reeves, who is the founder of gusto. Gusto is one of the largest and most successful payroll, HR and benefits companies of the modern era. And I'm really excited to learn how it was built and how things are going. So Josh, welcome to the conversation. Grateful to be here. All right. Well, let's start a little bit with some trivia about how you got into the space. What did you do before becoming a founder and what led you on the journey?

Joshua Reeves:

Yeah, so I love framing it as Gusto was started by three co-founders were all very involved and very committed.

You know, 13 years in, we feel like we're still early in the journey, but all three of us are electrical engineering PhD dropouts. And so how did we connect from that academic foundation to what we're doing today? I'll take you on the journey. So, for me, when I studied electrical engineering, I was at Stanford. It was really just a love of math and science and wanting to understand how things work. And I got exposure for the first time to startups. Even though I was born and raised in the San Francisco Bay area. My parents are both teachers. My dad taught high school in San Francisco, but it was much more in the humanities side. My dad taught English, history, social studies. My mom taught Spanish and French to elementary school kids. And so, Stanford was where I got, and my co-founders were all from Stanford. Exposure to not just how technology works and how to build technology, but it being used to go solve problems and that being a company. And if you can get leverage from technology, then you can solve big problems at scale.

And so that got me really excited about kind of pursuing that path. You know, start with a problem, try to fix something and obviously use technology as the primary way of doing it. But to connect the dots decided not to do the PhD. Kind of let go of some of that FOMO. Prioritization and focus are key. And I joined a startup, my first job out of school, this is back in 2005, was actually at an e-commerce company called Zazzle, still going strong. And I was there as a product manager, and that's really where I learned how to build software with a team, working with really amazing engineers, working with really amazing designers. And it was right at the advent of, you know, it's funny to say it now, given the focus on web three, but that was the advent of web two. That was when TechCrunch was first started. I remember going to barbecues and Michael Harrington's backyard. That was when Facebook was just down the street a few blocks from us with less than 100 employees.

So, I have a lot of stories from that period, if that's interesting to folks. And then in 2008, I started a prior company that was my first startup, and it was really, I would say me and a co-founder really just chasing, you know, building stuff initially for, for the audience of, you know, businesses and people on Facebook. Facebook had just opened up their platform. We did that for two years, and then we sold the business. And I can come back to that a lot more as well. But it was through that experience that I, you know, had to run payroll for a small team, had to do state tax registration, set up health insurance. And so, it was actually through that experience running a small business that I got exposure, and my co-founders did in their respective companies to some of the pain points that now gusto is very focused on solving.

Lex Sokolin:

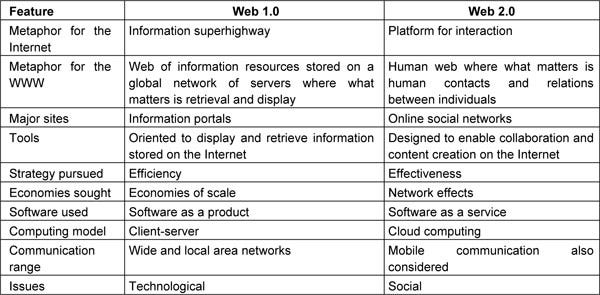

I'd love to go back to the Web2 period, and it's okay to have enjoyed it, regardless of what the Web3 people say. Can you tell me about what Web2 was trying to solve at that particular point of time? Like, what is it that everyone believed that was different from what was believed at the time, and kind of how did you absorb that lesson in trying to build along that path?

Joshua Reeves:

Yeah. So, for me, it connects a bit to even when I started school, I started my freshman year at Stanford in 2001. And remember, I had had exposure to, you know, tech and the dotcom era. But I was in high school, and I didn't really know any engineers myself because I was up in Marin County. So, across the Golden Gate Bridge, a little bit removed from Silicon Valley. And so, what I remember as being very interesting, my freshman year at Stanford was talking to a few people, you know, getting advice on what major to study. I had done some software in high school, and at that point in time, given the dotcom crash, what I remember thinking was, and it's funny to say this, but I remember thinking, there's no future in software.

This is all done. Everyone's so negative on it, you know, focus on electrical engineering, focus on the basics, get down to the hardware side of things. And that's what a lot of folks, including myself, did when we graduated 2005. And that was the advent of web 2.0. You know, half of my double E class joined Google, which had just gone public, and a bunch of the other folks joined, you know, Facebook, which had just, you know, got it started about a year earlier. And so, web 2.0 to me, to answer your question. And there's probably many takes on this. It was really kind of just reminding ourselves that there's this incredible impact and disruption coming from the internet because of how it levels the playing field, right? The ability for anyone to produce or at least make it easier for people to produce websites, Sites. Access information. A lot of the technology, the bandwidth, you know, the hardware, the wireless communications, the internet speeds all had to catch up.

But the fact that you could actually now do really interesting applications in a website, not just a, you know, a website that's static or kind of analogous to a newspaper back in the day or a magazine, but actually really complex actions. So, this is where, you know, things like Ajax working through JavaScript in the web browser. A lot of new technologies got developed in that time period or got brought back to the fore, and it was exciting. You could actually start doing more and more through a web browser and not needing to use desktop applications. And the company I joined, just to mention it was a part of that, like we were an e-commerce company. I joined right after the series A, and what Zazzle does is it enables anyone in the world to go design products that Zazzle then manufactures physically. And these started with things like cards and posters and T-shirts and is now expanded to, you know, dozens, if not hundreds of product lines. My focus as a PM was on the creators, the designers, and like, you know, we had artists all over the world.

My favorite was an artist in Uruguay named Alejandro, who would go upload his paintings, his incredible designs, and anyone then could go buy those designs. People would, you know, purchase them. Zazzle would manufacture it, print it, ship it out, and he would earn a royalty. He'd earn a percentage of that sale. And so now you had, you know, someone who was an artist anywhere in the world making a living, not having to do manufacturing, not having to do customer support. You know, he was making tens of thousands of dollars a year. And so that's to me, what web 2.0 was also about. It was just a reminder that the internet is this incredible distribution path for almost anything. In our case, you know, physical, digital products made physical. And that's incredibly empowering. And so it was really fun to be a part of that kind of reawakening around the web.

Lex Sokolin:

An enormous amount of entrepreneurship came out of that moment with people being able to build digitally native businesses, whether in manufacturing or in, you know, direct commerce, e-commerce distribution or in content creation and so on. And you very astutely saw this problem on the company management side with gusto. So, can you tell us more about what the pain points were at the time and maybe what the landscape of solutions looked like?

Joshua Reeves:

Yeah. So, let's fast forward to 2011 and there's some connection here to what we were just talking about. You have this technology, you know, tailwinds that sometimes people can overlook or, you know, maybe when they initially start, they get overly inflated. There's hype. Right. So that's, you know, back to the dotcom days. But as they progress, as these technologies advance, some of the things that were a dream become much more of a reality. So, you know, when we started gusto, we wanted to tackle a problem that we could spend decades, you know, making better, fixing it wanted. We wanted it to be a really big problem, very mainstream problem. So even though we had all felt the pain point of, you know, building a team, hiring someone, navigating compliance, local, state, federal rules, regulations, it's just way too hard to be an entrepreneur and it needs to be easier.

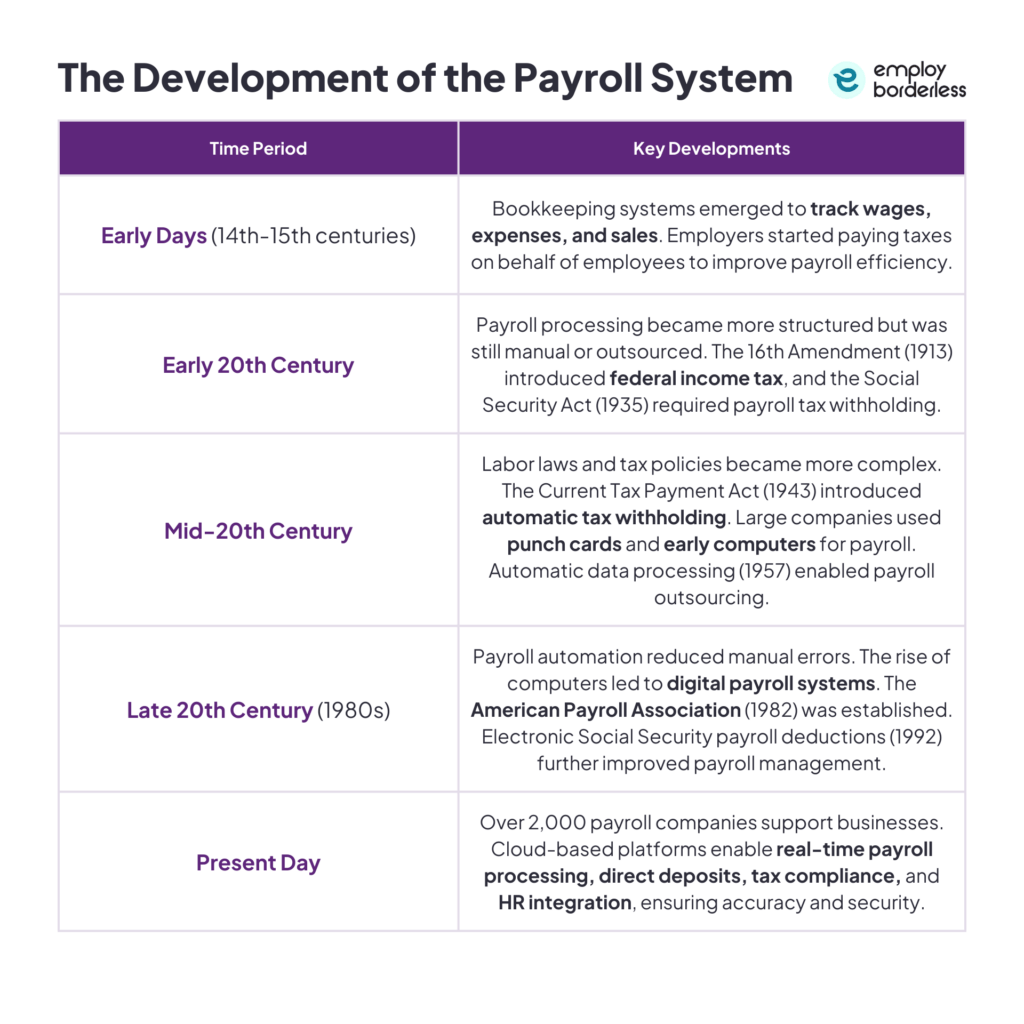

We also researched and found that a lot of other businesses had that same pain point in frustration when we started Gusto, and our first product is payroll. You know, 40% of companies in the US were getting fined for incorrectly doing their payroll taxes every year mistakes, penalties, fines being delayed, late incorrect calculations. So, it just felt like there was this gigantic problem here. And business owners don't go into running a business because they dream about how to do compliance filings. Better, faster, easier.

Lex Sokolin:

Why was this the case? Like why were they miscalculations? Why is it so manual?

Joshua Reeves:

Yeah. So that goes to the fact that things like payroll and we'll talk about a lot of our other products I'm sure shortly. But payroll predates the internet, right. The way they do payroll back in the, you know, 50s and 60s, 70s was by hand. So, you had at that point also, you know, close to half of the companies in the US 2011 doing payroll by hand, doing it manually, looking up tax tables manually.

And again, larger companies doing much more digital first, but far and away the common way to do things like payroll as a small business was manually. And that's because that's how it had been done for a long time. And so the technology tailwinds that we thought of as more of a hypothesis that became very much a reality. But you had cloud, right. That was catching on a lot in that time period. You had paperless and you had mobile, right? iPhone, Android, etc. And so, we thought, hey, with these technologies and we'll talk about distribution in a sec. Like we could create a product and experience that's in a web browser that's incredibly intuitive and easy to use that a small business can set up on in minutes, where they can go run payroll with no training, no background in running a business. This would be finally the catalyst for folks to shift off pen and paper and manual to a more software centric solution. Software is way better at following rules than people. It's going to be way more accurate, way more efficient, way more scalable.

And those are all hypotheses. Then we had to start building. But we felt like that was the future, right? It seems simple now, but that was not the norm for a small business when we started the company.

Lex Sokolin:

This is a bit of a silly question, but did you think of this as a fintech company at the time? You know, these days everything that touches money is a fintech company in name. But what category did you place yourself into?

Joshua Reeves:

So I would say we didn't even think about category because everything then and now starts with the customer. And small businesses, you know, don't really care what category a company is in. They want to know, are you making my life better? Are you fixing a pain point in my life? And so, you know, to answer from a category lens, the payroll has generally straddled. You know, if you want to look at historical categories, it's definitely a financial product. We're moving lots of money, Gusto today moves, you know, billions of dollars every day.

But it's also in the broader category of HR, HCM, human resource management type products because it ties to a team and people, the employer or the employee from a business model lens. It's SaaS. It's a subscription business model. We get, you know, paid every month for the service we provide. And, you know, our second product is really focused on health care. So, I kind of always say gusto is, you know, SAS, it's SMB, it's health tech, it's fintech. You know, what actually matters is we're helping small businesses, you know, succeed and thrive better. And that's really our due north.

Lex Sokolin:

Take us through the early days of the company. What were maybe some of the early wins and early losses in your experience?

Joshua Reeves:

Yeah, I'll try to go back to those early days. 2011. So 2011, 2012, we knew that there was this, again, big, broad kind of set of pain points around starting a business, running a business.

You know, too many challenges, roadblocks, things that make it hard. Only about half of new employers make it to year five is the historical stat. And so, payroll was the first thing we were going to focus on. We were three people. And, you know, we were three people who had never, ever built payroll software. So, the first thing we had to do was figure out, you know, how to go do tax calculations, how to go do tax payments, how to go, you know, prove that actually we could build what we were saying, we thought was, you know, the future. And we also added the fun, I guess, incentive that we weren't going to pay ourselves until we could do it using our own system. And so, we were a part of a Y Combinator. That was kind of the early 2012 timeframe. And, you know, early months were really focused on just building out that initial ability to in California for new businesses with only full-time employees, be able to pay yourself.

And it was mostly just the back end, the infrastructure piece of it. And so early phases of the product. This is the advice I give. Entrepreneurs you have to prioritize. You can have all these big dreams and ambitions, but if you don't break down the problem space and the kind of sequencing, it's really easy to try to do too much all at once. And so first big milestone for us was paying ourselves, then paying, you know, 5 to 10 other companies that we knew personally. And then from there it was a sequencing of, let's go really test this hypothesis of can we acquire and serve small businesses, mainstream small businesses, in a scalable way. And so we launched in December 2012. That was when we had a, you know, a website you could onboard set up in a self-serve fashion. If you want to call us, we'll talk to you, help you, of course, but really just trying to prove that you could as a company hear about gusto. At that time, we had a different name.

Send payroll. You could set up, you could add an employee, you could pay them and do it all in minutes and go, wow, that's magical. This is the future. This is so much easier. Better than doing it by hand. And so that's kind of what we focused on in that first year plus when we launched in California. You know, we had 100 companies sign up in that first month, and these were companies we didn't know all over the state, different industries. One of the big hypotheses or goals we had really was, you know, we love we love helping tech businesses. But there's, you know, there's more dentist offices in the US than tech startups. So really, how do we get into that mainstream business customer segment? And we knew it had to be through word of mouth. It had to be through good SEO, good content creation, but also just a really great product that people wanted to share with others. Because for this specific customer segment, you know, a high touch outbound sales motion doesn't work, right. ACV is much lower. So, you have to have a really, really strong organic flywheel.

Lex Sokolin:

It is well known how difficult it is to build a go to market strategy into small businesses. And I mean, just within the last eight months of our recording, this bench, which was bookkeeping and accounting provider for small businesses went out of business because they were losing money on the marginal customer. They were spending a lot of time trying to get the businesses in, and once they did, they had made the claims that software was automating all the bookkeeping. But end of the day, it ended up being services because it was too difficult to build a solution that worked for everybody. How did you get around this problem? That every small business is different, that they have an endless number of different things that they want, and at the same time, they have very low budget to actually spend on software.

Joshua Reeves:

Yeah. So, I think it really depends on the product you start with. I mean, you asked earlier about what are some of the challenges, difficulties? I mean, the thing that sounds simple in retrospect, but like what do you focus on? What is the prioritization? You know, and we had a lot of choice there.

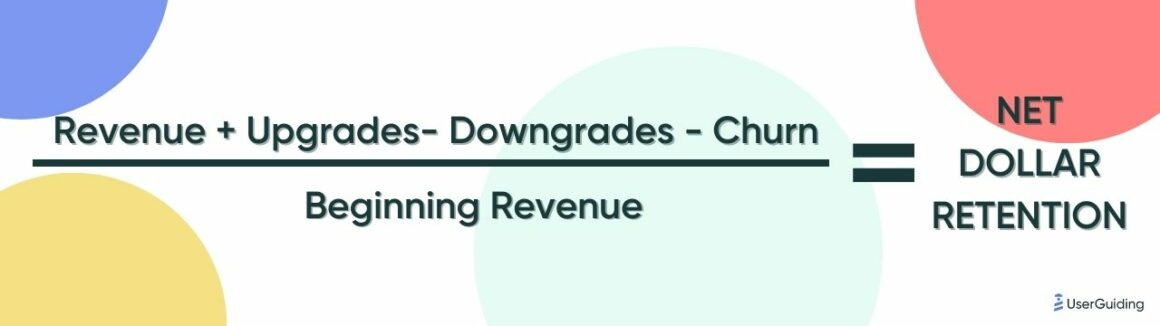

We had to kind of make the right choices for this to work out. One thing that helped, I would say, and I advise this to any entrepreneur, if you're focused on SMB, I think there's a phase where you're really in learning mode, incubation mode, you know, 0 to 1 mode where you're trying to figure out, you know, first, prove there's a real pain point. Second, prove you actually solve that pain point. And if you solve a pain point in B2B, you know that's called value creation. You know, you create value for the customer. They should be willing to pay you for that value. When I meet a entrepreneur and they say that customer is not willing to pay them for what they've created. I kind of wonder, did you create enough value? Did you actually solve enough pain in the life of that customer? But then a quick follow up to your question is if you're going to be in scaling mode now, you have to have really clear line of sight to what your unit economics are, what's your gross margin, what is your CAC and also what is your NDR.

Right. So customer acquisition cost, gross margin, you know how much you spend to serve the customer. And then under your net dollar retention, it's very easy in SMB, given the number of companies that just shut down to actually have bad unit economics. And from an acquisition lens, it's always easy to spend $5 to make $1. I would argue that's never a good idea. So, for us, it was really staying very focused on that organic flywheel engine. We didn't do really any paid acquisition, any advertising through Google until about a year after we launched. We wanted to figure out could we get to our targets and high growth rates with word of mouth with, you know, content creation, good SEO? And we had to prove. And then the other big thing that helped us was social, right? Like, people were sharing the word of mouth not just in person, but in avenues like Facebook and Twitter, etc. And so, to me, it just comes down to if you're going to be in scaling mode, incubation early stage, you can iterate, but if you're going to be in scaling mode, you have to have good unit economics.

And what helped with us was payroll is a very, very horizontal product. Everyone has this pain point. And you know, what also proved true was we could build a single product. There are not customizations per customer that actually does work for a very, very broad set of audience. And then payroll itself just happens to be one of the most sticky and least optional products for a business. If you don't pay someone you know, they quit, right? So, it's really the one of the last things, if not the last thing, you turn off if your business is struggling. So that helped a lot in terms of our strategy to get to, you know, our first product, being successful, having good unit economics, scaling. And then that also gave us the ability to start thinking about, you know, second, third, fourth, fifth products that we added really based on customer demand, customer pull things they felt like we could help solve that are very adjacent or connected to payroll, things like time tracking, things like health benefits, things like setting up a 401K or HSA, FSA. But all of that came from that initial payroll engine working really well, which continues to be a huge driver of our growth today.

Lex Sokolin:

Can you share a bit about those unit economics, like what does it cost to acquire a customer small business and what are the dynamics like for retention across the different products?

Joshua Reeves:

Yeah. So, I'll give some advice, maybe more on this without kind of going into lots of Gusto financials. But the advice I give entrepreneurs, you know, it's all directional. But you know, when you're in customer acquisition mode and maybe everyone in this podcast knows what these terms mean, I'll just give a little bit of a definition. But again is how much you're willing to spend to acquire a customer. And if you have a subscription business, there's really two parts to this. It's, you know, what are you willing to spend? And that usually gets measured by months of revenue is the simplest metric you can get into kind of gross profit cash as well. But literally how many months of revenue are you willing to spend to acquire a customer? But that closely coupled with what's your lifetime value of a customer, right.

And so, you know, 13 years in now we have lots of data on very, very long lifetime values, which is one of the strengths of our business. But there's a lot of products where, you know, if a customer tries it for six months and, and then is done using it or churns. That's a very low lifetime value, right? So, our lifetime value is in several years. And so then, you know, you're making a choice. How much of that many years of revenue are you willing to spend to acquire the customer? And I would say, you know, a good best practice is, you know, somewhere in the range of 12 months is very healthy. You can get more aggressive and go to things like, you know, 18 months when you start getting too far into the lifetime value. You're actually pulling forward all that revenue. And that becomes a little bit more like gambling, right? You're kind of making a bunch of staggered assumptions. And if the market changes, if you have, you know, two little initial signal and maybe the customer behavior, you know, goes down and they don't stay as long as you thought, you end up maybe even at the extreme, spending more to acquire them than they pay you.

You know, that's just not a good business, right? That's not a business ready to scale. If you spend more to acquire a customer than they pay you, that's just going to lead to lots of money getting lost and on gross margin. Same I think healthy growth margin at scale is, you know, in the 70s, if not the 80%. And that means that you're actually building a real business where, you know, they pay you and it costs you much, much less to go provide that service. I think the pitfall here is companies that have poor gross margins or even negative gross margins, and try to make it up at scale again, that can work at the extreme, but it's almost a bit more like gambling again, with a lot of assumptions built in. So, you know, those two metrics are what I would call unit economics how much you spend you acquire, how much you spend to serve. You want to make sure you have line of sight or hopefully just concrete reality of good metrics for something that's scaling.

And then the outcome is net dollar retention rate. How much someone's paying you in the first year. What does that look like? Two years, three years, four years in. And you want to see that number growing. You want to be over 100% NDR. And so, you know, my mental model is we've continued to launch new products, expand into new product segments. You know, we're an ambitious group. We have a lot more to do. Ahead of us is when you're in incubation, you're okay kind of testing learning. But if you're in scaling mode, you just better have good, good unit economics for that part of your business.

Lex Sokolin:

Can you talk about kind of the ladder of new product rollouts? And it'd be great to understand how the different products were built upon each other. And how did you get that customer demand to be very clear about prioritization of what should be rolled out. And then a connected question would be, how did you scale your product organization in order to be able to deliver this?

Joshua Reeves:

Yeah, and I'll try to frame it through advice for folks.

Gusto as a case study. But obviously there's many ways to approach these topics for us. Gusto as a team we're now, you know, 2,600 people strong customer is always our due north. We exist to serve customers. I don't believe companies exist for their own benefit. Companies exist to solve problem for their customer. And so, a big part of our journey of expanding our product mix is talking to our customers, listening to them, hearing what they're asking us to help with. You know, and that's a huge piece of signal for us. There's also, you know, spoken need and unspoken need. So, there's obviously judgment involved as well. But we always had hypothesis even from our seed fundraising deck back in 2012 around a whole bunch of adjacent, you know, products and areas that just feel like should all be solved in a more holistic, integrated way. Running a small business is hard. You're wearing 20 different hats, and you don't want to kind of be responsible to go use 20 different systems or products and kind of stitch it all together yourself.

And so, the number one, just to go through kind of the first additional product we added. Number one thing we had customers ask for and has a very close connection to payroll was benefits. It's a deduction right. There's obviously usually an employer contribution. This is typically employer sponsored health care. So, there's a connection to payroll in terms of the contributions. You know the employee component the employer component. It's a bit analogous to payroll in that you have all of these complex third parties. So, in payroll, that's the local, state, federal tax agencies. There are over 10,000 tax rules across the country. There's a lot of compliance inflation happening where there's more and more rules and requirements that make the job of a business owner harder. We want to go abstract all of that. But similar on health benefits, which should be this amazing product that gives you peace of mind. And, you know, if your kid gets sick, you know, they're going to be covered and they're going to get the care they need.

There are all these insurance carriers that also have complex enrolment processes generally are not super digital first. And so, we saw an opportunity to go abstract and simplify that. So, what that meant was we were going to become a broker. We're not the one actually you know providing the health care. We're setting up our customers with health plans from Blue Cross Blue Shield, Kaiser, etc. And what was painful at the time, to your question was the team was still pretty small. You know, we had payroll as a product doing really well, growing, you know, hitting plan and exceeding it. But the engineering team. I want to think back to kind of 2014, 2015, you know, it was probably still like 30 people. And the idea of taking, you know, 5 to 10 of those 30 people and focus them on a second product was really difficult because we had so much to do still on payroll. We had just hit nationwide coverage. It took us a couple of years to get to all 50 states.

So early 2015 was when we achieved 50 state coverage, which was really important for us to support a business that hired employees in multiple states. And so, you know, thinking through the right talent, thinking through now, having two different product teams or product lines, if you will. You know, that's why we raised money. I actually think the main goal of raising venture capital isn't to make up for a bad business. If you, you know, everyone just listened to me talk a lot about business model. You need to have a good business model when you're scaling. But we do want to collapse time. And we wanted to pull forward revenue. And that's why we raised venture capital to build R&D teams, build engineering teams faster, to go launch more products more quickly. And so there too. We had to sequence, you know. We launched in California. It was just new plans. So, folks who had never had health care before setting up their health plans for the first time. And once that was really working, it, you know, hit very high attach rates, win rates, then it was back to, you know, expanding this to more states, adding more functionality, etc.

Lex Sokolin:

Can you double click on the organizational setup question because, you know, going from ten people to 2,600 people is a once in a lifetime experience for very few people. And the things that you start out thinking about leadership and management and human nature and the kinds of systems that work for you, really change as you start getting into larger and larger sizes. So, I'm really curious as to how you developed the organizational structure. And then maybe what were the phases of that as you scaled up?

Joshua Reeves:

Yeah, I'll try to break it down into some big chapters, because the reality is that we're always trying to improve, always iterating, always adapting. But yeah, I mean, you heard a little bit of my background. I never run a company of this size and scale before. You know, once we passed five employees, every single size threshold was the biggest company I had ever led. So, for me, I would say one of the things I really recommend to all entrepreneurs, and I think it's pretty innate to an entrepreneur.

But growth mindset, you know, realizing that there's a really important need for feedback. The curiosity drives my desire to, you know, ask tons of questions. I'd say we were very fortunate. We did have 20 angel investors. They were mostly founders, CEOs. So, the chance to talk to them and hear their advice on what they had gone through and to be really tactical about it, it's like, how do you evolve your hiring practice? How do you evolve your all hands practice? How do you evolve your planning and budgeting and decision-making process. How do you, you know, decide who's responsible for what. And there's all these different choices there. And a lot of times it's not black and white the right way or the wrong way. There's a lot of nuances. So yeah, to think of the chapters, you know, first chapter, we're all just building, we're all ICS, we're all just writing code. We're trying to figure out can we make something useful? Once we actually realized it was really useful, and customers loved it? Now we're building the team.

So, a lot of my focus shifted to recruiting, hiring. I have two other co-founders. We had a really clear division of responsibility. Tomer focused much more on product and design and customer experience. Eddie focused much more on engineering. I focused much more on go to market customer acquisition. You know, how do we grow? Plus, everything kind of business related, you know, finance, legal people, all the kind of operations part of running gusto. You know, one advice I have when you start hiring and recruiting, every interview you have isn't just you evaluating the candidate, they're evaluating you, but they're also just incredible learning opportunities like I remember. You know, I'm hiring now for the first time a finance leader. I'm hiring for the first time a legal person. I'm hiring for the first time. You know, a, you know, inbound content marketing person. You know, every time I met, you know, usually several people for every one of those searches before we made a decision, I just peppered them with questions and asked them about the field, how it works, who does what, what are the approaches? Which companies do you admire? So again, interviewing can be an amazing avenue to learn really quickly and then ultimately, you know, figure out which candidates resonate with the approach you're choosing to take.

But second Big Chapter is now building out, you know, a layer of leadership in the company. You know, we can't have everyone reporting to one person. A lot of times for Gusto, that meant promoting from within, although we did also bring in some folks. When you're at that company stage ten, 20, 30, 50 employees, you know, you still want every leader, Quote unquote. They're still doing a lot of IC work. They're still actually, if they're in marketing, writing lots of copy, they're still if they're in engineering writing lots of engineering code, if they're in sales, they're definitely doing lots of sales directly. I was the first salesperson at Gusto, and I was going to conferences for accountants and bookkeepers. You know, I was meeting small businesses, but then you get into a couple of hundred employees, and now I'd say the big shift is, you know, you don't know everyone by name. It becomes now an organization where it's not really possible to, to have direct personal relationship with every teammate, nor is that healthy.

You know, I think it's hard if you try to be close or know, you know, 2 or 300 people. It just doesn't work. And so, you have to really trust people around you to kind of be that abstraction. And there's a big choice. You know, what do you delegate or give others the choice to go decide. And what do you, in this case as CEO, which is my role. Maintain direct involvement with and I wouldn't say there's a formula there. I think CEOs need to be very involved in the details. They need to stay close to the work. and you know the name of the game is bringing in great talent. You can go empower to go do great work. Otherwise, it's really easy for a CEO to become a bottleneck. So, both pitfalls are worth avoiding. You know, you don't want leadership to be disconnected, but you bring in some amazing talent. And I was bringing in we were bringing in some great, great folks to guest. So, you really want to let them run and do their job and impact the org beyond your expectations or approach? Maybe the last chapter I'll highlight is just, you know, when you're really bringing in quote unquote executives, you know, you have several hundred, if not a few thousand employees now.

And I think the key thing there is to make sure whoever you're bringing in is ready to work at the stage you're at. I definitely made some mistakes in that process where, you know, someone could have been great for gusto, but maybe three years later, not at the stage we were hiring because there was much, much less of the infrastructure and the building blocks. You know, we want leaders coming in to build the building blocks. And so, there's a calculation always on, you know, making sure the talent you're bringing in is, is the right fit for the stage you're at. Given the puzzles and challenges ahead.

Lex Sokolin:

In terms of, for example, like when you decided to have multiple products built, one direction for organizational structure is a bit more functional and hierarchical, right? When you've got people who are running marketing and people who are running technology and people who are running product, and then you're putting teams together to work on new initiatives and new products, but they're still rolling up functionally versus the what is maybe a bit more popular as a management philosophy in big tech these days, which is kind of the Amazon approach with, you know, five people around a pizza and lots of ownership for product leaders.

And which of those were more intuitive to you, or is there some sort of, you know, matrix organization that that you've put in place? So when you're looking at launching those additional products that have become successes, how did you organize and mobilize the team to do it?

Joshua Reeves:

Yeah. And our learnings insights have evolved. I mean, just going back to benefits and definitely still how we approach brand new products. We like the mental model of thinking of it as kind of like a carve out. You want to have a smaller team as possible. You know, whereas many hats as possible and be as obsessively focused on, you know, what they're trying to go achieve with as little distraction as possible. So maybe that's maybe that's similar to the Amazon approach you're describing. But there's definitely a dynamic when you're a bigger company where you know, good intent. But how do we do broader planning or budgeting, which is just necessary when you have, you know, this amount of people can actually get in the way of a small team just, you know, obsessively chasing and pursuing, proving, you know, that they can build a product that provides value to your customers.

So, we still like that model. If you've heard of the horizon model, that's kind of horizon three type work. You want to have again, a small team with as much autonomy as possible, really just go prove product market fit. You know, go prove that we can solve that pain point. And then there's a kind of next part to it, which is if you're going to scale it. Fortunately, you know, new products from gusto are not scaling independently and have to go get their own customers. A lot of times for us, it's we're bringing those products to our existing customers set. So, there is a need for that now to connect to the rest of the organization. And some of the products we launch, by the way, are not first party, only built by gusto. We also do third party products like how we solve the for one pain point for customers today is through partners, you know, integrated products, often embedded products that you know, really are great, you know, do the job and have been built by other companies.

And we can be a partner to them to reach the small businesses that they might have a hard time on their own getting to from an org design lens, I'd say companywide today. You know, we probably describe it as a matrix. I do think about these swim lanes of each product, each app, you know, each capability we're launching. We want people in those swim lanes to be 100% dedicated to the area they're in. So, you know, the benefits team is as a set of products, you know, folks, PMS, engineers, designers that live and breathe that problem space. The folks focused on hourly time tracking, shift scheduling, you know, time clock management. That's a team all obsessively focused with that set of pain points. We do have, you know, different functions there, right? I mentioned earlier like engineering design product. We try to make sure we don't just have functions for the sake of it. It should be folks that are relevant to solving that pain point and making sure we deliver a great product in the in the broader how it rolls up in the company, you know, that's where you get into the classic debate, you know, are you more GM structure or are you more functional structure.

You know, there's pros and cons to both. I've talked to a lot of, you know, much bigger company leaders on this topic. And you just have to find what's right for you for the phase you're in. We've actually shifted a few times when we were, you know, only 1 or 2 products. We were very, very functional. As we got to having several products, we saw a lot of power in having these swim lanes with, you know, dedicated teammates and a bit more of that GM structure. But there's pros and cons to both. I wouldn't say there's a right or wrong for every company.

Lex Sokolin:

Can you tell us a bit more about the size and scope of the company today, just in terms of whatever you can share on, you know, the economics, and maybe from there we can lay out where you think the company is going in the future.

Joshua Reeves:

Yeah, I mean, we're proudly serving over 400,000 businesses on gusto. So that's about 7% of all employers in America.

We think that's still just the early days of what's possible. It's a very fragmented market. You still have a lot of folks on pen and paper. We have incumbents in this space that we compete with. But again, what was always striking to us was how fragmented the market was and how many folks are still doing the type of things we help with in a very manual fashion. We've publicly stated we don't kind of do this as a regular update because we're a private company. But a couple of years ago we passed, you know, 500 million of revenue. So, it's a good business. We've been free cash flow positive. Our mental model for free cash flow is, you know, at scale products generate free cash flow because they have good business fundamentals. And then we reinvest that free cash flow because we want to be really aggressive in expanding our product portfolio, solving more pain in the life of our customer. You know, we have lots to do. We have, you know, dozens if not hundreds of more products to go build.

We have, you know, millions of businesses to go help that are currently, you know, doing a lot of what we offer again by hand and making mistakes and getting penalties. So, one decade in many, many decades to go definitely as a founder crew, we think of this as a kind of lifelong journey where we want to dedicate all of our professional working time if we do our job right, you know, we're making entrepreneurship easier. We're making it better so that there's more. Companies started every year. About 500,000 new employers get started every year. We think that number should grow a lot and only about half make it to year five. We want to increase that percentage a lot as well.

Lex Sokolin:

How do you think about the overall market environment and kind of the competitive pressure that's now in the space where you've built this company, like you're one of the founders of the space because it's been so successful and there's so much promise you have. I mean, you're lucky to have very good competitors. In addition to that, you know, some of the underlying dynamics of what payroll is and how money moves and what banking is have changed as well, right? Whether it's new types of payment processing systems, expectations around large global footprint, more complexity around account types and so on.

So how do you think about navigating competition and then how do you think about general structure of the industry in which you are?

Joshua Reeves:

Yeah, I mean, the number one thing when it comes to competition is just going back to our core philosophy. We are here to serve our customers. That means we need to be the best product. We need to be the best experience. We need to solve the pain better than anyone else. And that's what's most in our control, right? If we're not delivering that, then that's work for us to get better at. And if we are, that's a big part of how we've been so successful, or at least successful today in gaining market share, you know, winning many more customers than we lose from competitors and retaining, you know, customers on the gusto platform. We haven't been perfect by any stretch. But I would say for any entrepreneur out there, number one, focus on what is in your control, which is always going to be your product quality and you delivering on the value prop of what you promised your customer.

And if you're really, really focused on that and doing that, great and really also ambitiously investing in, you know, expanding what you do for your customer based on clear things that they need and would like your help with. That's a great way to be a winning kind of company in a competitive space. Second point, you kind of alluded to it, but if there isn't a lot of good competition, you know, then I wonder when I meet entrepreneurs, is it a good space? Right? I think this is one of the highest potential spaces out there. It's pretty foundational if you think about, you know, capitalism, the nature of work, a company, people getting paid. You know, employers and employees, these are all foundational concepts. And the space we're in has the potential, you know, for us to go serve, you know, millions of businesses and solve not vitamin pain points in their life but medicine pain points. Right. You got to pay someone otherwise they quit.

You know, health benefits are a very, very foundational need in many, many businesses, etc., etc. But yeah, in terms of evolution, you know, that's the fun part. We like to be aware of it. I would recommend folks. You know, there's maybe two extremes here. One, you know, be aware of everything and anything happening in your space. But two, that doesn't mean you should become reactive to it. You know, play your own games, set your own strategy, make sure you're executing it in a way that makes sense, and the outcome should be also tracked. Are you winning market share? Are you growing faster than others? Are you retaining customers. If you get negative signal on any of those dimensions, and that's a really good reason to revisit your strategy. But we're really focused on maintaining our leadership position, continuing to grow market share, continuing to grow while at share with the pain points that we solve. And we feel really bullish on the future.

Lex Sokolin:

Well, thank you so much for coming on today. If our listeners want to learn more about you or about gusto, where should they go?

Joshua Reeves:

I would just come to gusto.com. I don't really use Twitter too much, but I have published various content. You know, I try to be helpful to the entrepreneurial ecosystem. One of the things I really believe is it's not a zero-sum game when it comes to founders tackling problems. I know a lot of this audience is either founders or aspiring founders. You know, it's an amazing, amazing thing to take that plunge. And I would just counsel you again. It starts with, is there a problem? Is there a pain point that you really feel compelled to go fix and make better? And if you find that and if you can show that you're making it better. There's a lot of other downstream stuff that has to line up. You have to have a good business model; you have to have a good go to market.

But it's one of the most incredible experiences ever to see a customer and tell them and have them tell you, you know, thank you. Like you've made XYZ better, made my life easier in this specific way. That's what drives me every day. I know that's what drives a lot of entrepreneurs. And so yeah, kudos to everyone that has taken that plunge, and I hope everyone the best of success.

Lex Sokolin:

That's so inspiring. Thank you and hope to have you on the podcast again.

Joshua Reeves:

Thanks so much, Lex. It's a lot of fun.

Postscript

Sponsor the Fintech Blueprint and reach over 200,000 professionals.

👉 Reach out here.Read our Disclaimer here — this newsletter does not provide investment advice

For access to all our premium content and archives, consider supporting us with a subscription.

Share this post