Fintech 101: Neobanks

Introduction to core sectors

Hi Fintech Futurists,

Below you will find the history of Neobanks, including key articles and illustrations.

We are using the many years of Blueprint analysis archives to build out definitional introductory content for our key coverage pillars. Here is the table of contents:

Early History

Industry Context and Development

Business Model and Market Size

Product Structure

Venture Capital

Going Public

Ongoing Challenges

Differences by Country

Interaction with Fintech, Crypto, AI, and Other Technologies

Make sure to 💲upgrade💲 to access deeper analysis linked throughout, which enhances the overview with key deep-dives and conversations with industry founders.

Thanks as always for reading,

Lex

Early History

Genesis

Neobanks did not emerge in a vacuum. Their rise is tied to a sequence of financial crises, regulatory shifts, and technological advancements that reshaped how consumers interacted with money. While the idea of branchless banking has been discussed since the late 20th century, the 2008 financial crisis was the catalyst that set the stage for their arrival.

The collapse of major banks and the subsequent tightening of financial regulations created an opening. Governments across the world, particularly in Europe, sought to introduce more competition into banking. The United Kingdom’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) spearheaded this movement by lowering barriers to entry for new banking firms. Germany’s BaFin followed a similar path, granting specialized banking licenses to digital-first players. These changes allowed startups to challenge legacy banks in ways that were previously impossible.

In parallel, the European Union introduced the Payment Services Directive (PSD2) in 2015. This legislation forced banks to open their APIs to third-party providers, effectively allowing fintech startups to build financial services on top of existing banking infrastructure. With this framework in place, digital challengers could offer near-instant account creation, real-time payments, and low-cost international transfers.

The first major neobank success stories emerged between 2010 and 2015. One of the earliest examples was Simple, a U.S.-based digital banking startup launched in 2009. Simple positioned itself as an alternative to traditional banks by offering a mobile-first experience with built-in budgeting tools. Though it gained traction, it ultimately struggled with profitability and was acquired by BBVA in 2014 before shutting down in 2021.

Europe, however, proved to be the more fertile ground for neobank expansion. Berlin-based N26 launched in 2013, initially as a financial management app before securing a banking license in 2016. By 2020, it had expanded into 25 markets with over five million customers. In the United Kingdom, Monzo was founded in 2015, first offering a prepaid card before transitioning to full banking services in 2017. It quickly became one of the most widely recognized digital banks, with millions of customers and a loyal base of early adopters. Revolut, another UK-based fintech, followed a different path by focusing heavily on foreign exchange and crypto trading, growing into one of the most well-funded fintech startups in the world.

Scaling

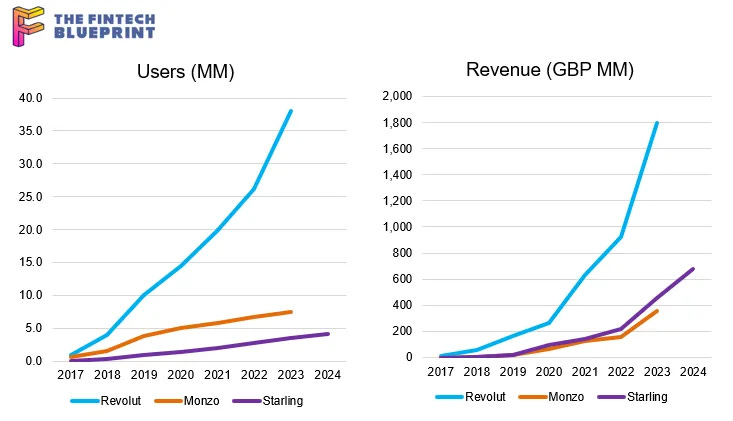

Between 2015 and 2020, investor enthusiasm for neobanks reached extraordinary levels. Revolut, Chime, N26, and Monzo collectively raised billions in venture capital, fueling rapid expansion and aggressive customer acquisition campaigns. Chime, which launched in the United States in 2013, capitalized on a fee-free banking model and a slick mobile app. By 2021, it had surpassed 12 million customers and secured a $25 billion valuation. Revolut reached a staggering $33 billion valuation after an $800 million funding round in 2021, despite never having turned a profit.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a turning point. While digital banking adoption surged, the challenges of operating a profitable neobank became increasingly clear. Many firms relied on interchange fees from debit card transactions, a model that proved unsustainable without significant scale. Others experimented with subscription-based revenue, business banking, and lending, but profitability remained elusive. N26 ultimately withdrew from the U.S. market, citing regulatory complexity and high operational costs. Meanwhile, Starling Bank in the UK distinguished itself by turning a profit in 2021, largely thanks to its lending business.

By 2023, the question was no longer whether neobanks could attract users but whether they could become financially sustainable businesses. Some firms began exploring public offerings, while others focused on expanding lending operations or forming partnerships with established financial institutions. What began as a niche experiment in digital banking had grown into a multibillion-dollar industry, permanently altering the competitive landscape of financial services.

Industry Context and Development

The financial services industry has historically been one of the most difficult to disrupt. Decades of regulatory protections, entrenched customer behavior, and the sheer scale of traditional banking institutions made meaningful competition nearly impossible. However, the last fifteen years have seen a fundamental shift in how financial products are developed, distributed, and consumed, paving the way for neobanks to become a legitimate force in global finance.

The emergence of neobanks is not just a story of startups challenging incumbents. It is a reflection of deeper trends: the digitization of commerce, the unbundling of financial services, and a regulatory environment that has gradually allowed for more experimentation. At the core of this transformation is the rapid adoption of smartphones. By 2020, global smartphone penetration had surpassed 80%, fundamentally changing how people interact with money. Consumers became accustomed to digital-first experiences, from shopping on Amazon to hailing a ride on Uber, and the expectation that banking should be equally seamless became a powerful force for change.

At the same time, traditional banks were slow to evolve. While major institutions invested heavily in digital transformation, many still relied on decades-old core banking infrastructure that made innovation difficult. Most banks built their businesses on physical branches, high-fee structures, and complex regulatory moats that kept new entrants at bay. This created an opening for digital challengers that could offer a superior user experience at a lower cost.

Regulation

Regulatory shifts played a critical role in enabling the neobank wave. In Europe, PSD2 forced banks to provide open access to customer data through APIs, allowing fintech startups to build competing financial products. This led to a wave of innovation, particularly in the UK, where regulators actively encouraged challenger banks to enter the market. In 2014, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority introduced a fast-track licensing process that enabled digital banks like Monzo, Starling, and Revolut to launch full banking operations in just a few years.

The United States presented a more complex landscape. Unlike Europe, where regulators encouraged competition, the U.S. banking system remained highly fragmented and difficult to navigate. Most neobanks, including Chime and Varo, initially operated as fintech firms rather than full banks, partnering with smaller chartered banks to provide core banking services. Varo later became the first neobank to receive a national banking charter in 2020, marking a significant milestone in the industry’s development. However, the regulatory environment in the U.S. has continued to pose challenges for digital banks looking to scale.

Super Apps

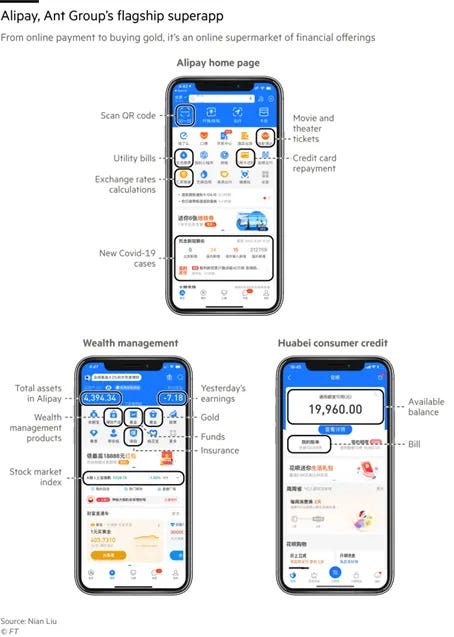

Asia has followed a different trajectory. China led the way in digital finance through platforms like Alipay and WeChat Pay, which effectively function as mobile-first banking ecosystems. In contrast, India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI) created a government-backed digital payments network that allowed fintech firms to compete directly with traditional banks. Meanwhile, Southeast Asia has seen a surge in digital banking activity, with Singapore and Indonesia emerging as major hubs for fintech innovation

.

Latin America has also become a key battleground for neobanks, with companies like Nubank in Brazil redefining financial services for millions of unbanked and underbanked consumers. Unlike their counterparts in North America and Europe, many Latin American neobanks have focused on financial inclusion, providing access to banking services for customers who previously had no access to credit or digital payments. Nubank, for example, has grown to over 70 million customers and achieved profitability in 2022, proving that digital-first banking can be both scalable and financially sustainable.

The industry’s development has also been shaped by the role of venture capital. Between 2015 and 2021, global investment in fintech surged, with neobanks raising billions to fuel growth. Investors were drawn to the promise of high-margin financial services and the potential to disrupt legacy banking institutions. However, as interest rates rose and funding conditions tightened in 2022 and 2023, many neobanks found themselves under pressure to prove they could generate sustainable profits. The focus shifted from aggressive expansion to building viable business models, leading some firms to consolidate, pivot, or exit unprofitable markets.

Despite the challenges, neobanks are now firmly embedded in the financial system. Traditional banks have responded by launching their own digital-first brands, partnering with fintech firms, or acquiring challenger banks outright. At the same time, regulatory bodies continue to evolve their approach to digital finance, balancing the need for innovation with concerns over financial stability and consumer protection.

Business Model and Market Size

Economics

Neobanks operate on a fundamentally different business model from traditional banks, favoring digital-first strategies that prioritize scale and low-cost operations over legacy infrastructure. Unlike traditional financial institutions, which generate revenue from a mix of lending, wealth management, and fee-based services, neobanks initially focused on customer acquisition through zero-fee banking, high-interest savings accounts, and streamlined user experiences. Over time, as the market has matured, their business models have evolved to include premium subscription services, lending products, and strategic partnerships.

A key factor that differentiates neobanks from incumbents is their low cost-to-serve. Without physical branches, neobanks operate with significantly lower overhead, often spending a fraction of what traditional banks do per customer. For example, the cost of servicing a customer for a digital bank can be as low as $20 per year, compared to over $200 per year for a traditional bank. This cost efficiency allows them to offer competitive pricing and better incentives, attracting millions of users in a short time.

In their early years, most neobanks relied on interchange fees as their primary revenue source. When customers use their debit cards, the bank earns a small percentage of each transaction. This model was particularly lucrative in the United States, where banks with under $10 billion in assets were exempt from the Durbin Amendment’s cap on interchange fees. This loophole allowed companies like Chime to thrive by collecting 0.8% to 1.5% per transaction, significantly higher than what larger banks could earn.

However, interchange revenue alone was not enough to sustain long-term profitability. As a result, neobanks began diversifying their revenue streams by introducing subscription-based premium accounts. Revolut, for example, offers Revolut Premium and Metal, which provide features such as higher foreign exchange limits, travel insurance, and cryptocurrency trading. These plans, priced between €7 to €14 per month, have become an important driver of revenue, accounting for over 30% of the company's income.

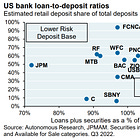

Importance of Lending

Lending has been the final frontier in neobanks’ quest for profitability. Unlike traditional banks, which generate most of their income from lending, neobanks initially avoided credit products due to the regulatory complexity and risk involved. However, as they matured, many launched personal loans, overdrafts, and credit cards to boost revenue. Starling Bank in the UK was among the first neobanks to successfully build a profitable lending portfolio, achieving profitability in 2021. Nubank in Brazil followed a similar path, leveraging its credit card business to scale to over 70 million customers and turn a profit in 2022.

The global neobank market has expanded rapidly, fueled by increased smartphone penetration, fintech adoption, and regulatory support for open banking. By 2023, the market was valued at over $66 billion, with projections indicating a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 45% through 2030.

In terms of user base, neobanks have amassed over 500 million customers worldwide, with the largest players concentrated in Europe, North America, and Latin America. Nubank in Brazil leads with over 70 million users, followed by Revolut (35 million), Chime (14 million), and N26 (8 million). While some neobanks have struggled with expansion into new markets, the overall trend remains positive, with increasing consumer preference for digital banking services.

Despite their rapid growth, many neobanks still face profitability challenges. The cost of customer acquisition remains high, particularly in competitive markets where digital marketing expenses can quickly erode margins. For example, Monzo reported losing over £100 per customer in its early years, highlighting the difficulties in monetizing free banking services.

Additionally, regulatory scrutiny has increased, particularly around anti-money laundering (AML) compliance and customer verification standards. Several neobanks, including Revolut and N26, have faced regulatory investigations for weaknesses in their KYC (Know Your Customer) and AML processes, which have slowed their growth in key markets.

Product Structure

Packaging

The core appeal of neobanks lies in their ability to offer banking services that are more intuitive, flexible, and cost-effective than those of traditional banks. Their product structure is built around digital-first experiences, real-time transactions, and an emphasis on financial accessibility. Unlike incumbents that rely on complex pricing models with hidden fees, neobanks have positioned themselves as transparent, customer-centric alternatives. However, as these companies have evolved, their product offerings have expanded beyond basic banking into lending, investments, and even cryptocurrency trading.

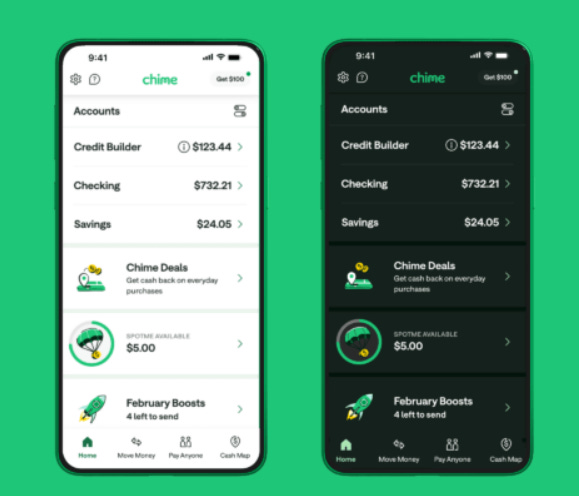

A standard neobank product suite begins with a zero-fee checking account and a debit card. This is the foundation of most digital banks, designed to attract mass-market customers who are dissatisfied with the fees and rigid structures of traditional banking. For example, Chime in the U.S. built its brand around fee-free banking, avoiding overdraft fees, monthly maintenance charges, and minimum balance requirements. European players like N26 and Revolut followed a similar path, using no-fee accounts as a gateway to deeper customer engagement. These accounts typically integrate instant notifications, budgeting tools, and smart savings features.

While basic checking accounts serve as an entry point, neobanks have added premium tiers to generate additional revenue. Revolut offers three subscription levels—Standard (free), Premium (€7.99 per month), and Metal (€13.99 per month)—each unlocking features such as higher withdrawal limits, enhanced foreign exchange rates, and travel insurance. N26 has a comparable structure with N26 Smart, N26 You, and N26 Metal, where higher-tier users receive exclusive perks and additional financial insights. These premium plans have become a significant revenue source, with Revolut’s subscription business contributing more than 30% of its total income.

Another key feature of neobank accounts is early access to payroll deposits. Chime’s “Get Paid Early” feature allows customers to receive direct deposits up to two days in advance, which has proven particularly popular among younger and lower-income users who value quicker access to funds. Starling Bank in the UK offers a similar feature, reinforcing its focus on cash flow flexibility.

Additional Features

Beyond basic banking, foreign exchange and cross-border payments have been a major differentiator for neobanks. Revolut built its brand on offering low-cost currency exchange, allowing users to hold multiple currencies and convert between them at interbank rates. This was particularly disruptive to traditional banks, which typically charge high fees and offer poor exchange rates for international transactions. Wise (formerly TransferWise) has also become a leader in this space, focusing on fast and low-cost international remittances.

As competition has intensified, neobanks have expanded into lending products to improve margins. Starling Bank has been one of the most successful in this area, leveraging its full banking license to offer overdrafts, business loans, and personal credit. Other players, like Monzo, have introduced Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) options, positioning themselves against fintech competitors such as Klarna. However, lending remains a challenging space for many digital banks due to regulatory requirements and risk management concerns.

Cryptocurrency has been another frontier. Revolut led the charge by enabling customers to buy, sell, and hold crypto assets directly within its app. The integration of digital assets into banking services blurred the lines between traditional finance and decentralized finance (DeFi). N26 launched a crypto trading feature in 2022, while Nubank introduced its own digital asset exchange in Latin America. However, regulatory scrutiny has complicated these offerings, particularly in Europe and the U.S., where authorities have expressed concerns about consumer protection and money laundering risks.

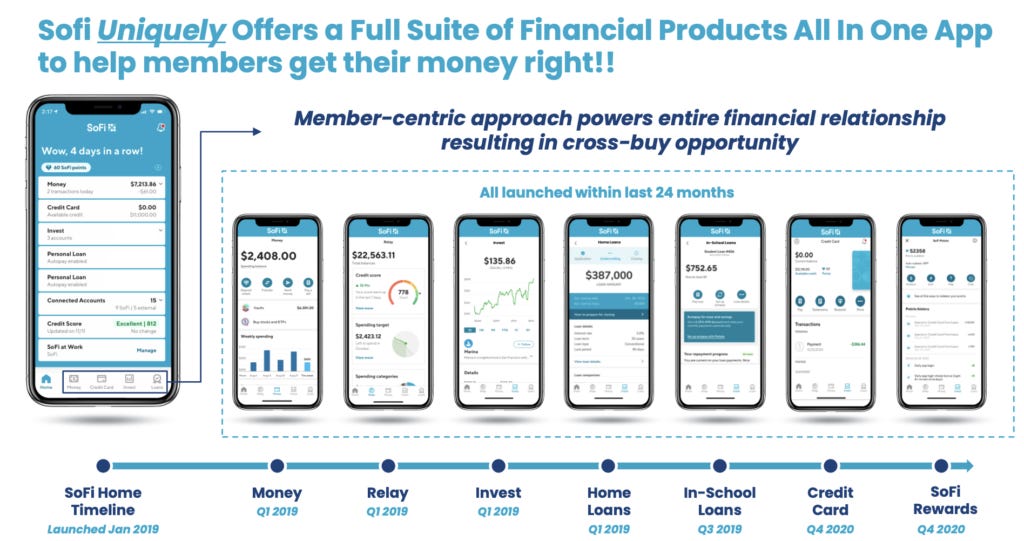

Neobanks have also ventured into wealth management. Nubank’s acquisition of Easynvest in Brazil allowed it to offer commission-free investing, competing directly with platforms like Robinhood and eToro. Revolut introduced stock and ETF trading, targeting retail investors looking for an all-in-one financial platform. Some neobanks, like Monzo, have experimented with pension and insurance products, though these offerings remain in early stages.

Business Banking

On the business banking front, neobanks have aggressively targeted small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Starling Bank, which generates a significant portion of its revenue from SME accounts, offers free business banking with integrated invoicing and accounting features. Revolut Business provides multi-currency accounts, corporate cards, and expense management tools, catering to freelancers and global businesses. This segment has proven to be a lucrative area, as SME customers tend to have higher balances and a greater willingness to pay for value-added services.

Despite these innovations, neobanks still face challenges in product differentiation. Many of their core features—no-fee accounts, budgeting tools, and digital wallets—have been replicated by traditional banks, forcing neobanks to continuously expand their offerings. Additionally, reliance on third-party banking infrastructure (e.g., banking-as-a-service providers) has limited the control some neobanks have over their product development and margins.

The next phase of product evolution in neobanking will likely focus on deeper financial integration. Open banking initiatives, AI-driven financial management, and embedded finance solutions will shape the industry’s future. Companies that can successfully transition from single-service banking apps to full-fledged financial ecosystems will have the best chances of achieving long-term sustainability.

Venture Capital

Investments

Venture capital has been the primary fuel for neobank growth, enabling digital banks to expand rapidly and acquire millions of customers. Between 2015 and 2021, the fintech sector saw a flood of investment, with neobanks raising billions of dollars on the promise of disrupting traditional banking. However, the funding environment has shifted dramatically since 2022, as investors now demand clearer paths to profitability before committing further capital.

At their peak, neobanks were among the most heavily funded fintech startups. Nubank, the largest neobank in Latin America, raised $2.3 billion before going public, including a $750 million round led by Berkshire Hathaway. Revolut, one of the most well-known European neobanks, hit a $33 billion valuation in 2021 after an $800 million funding round from SoftBank and Tiger Global. Chime, the U.S.-based digital bank, secured $750 million at a $25 billion valuation in 2021, making it the most valuable consumer-facing fintech in the country.

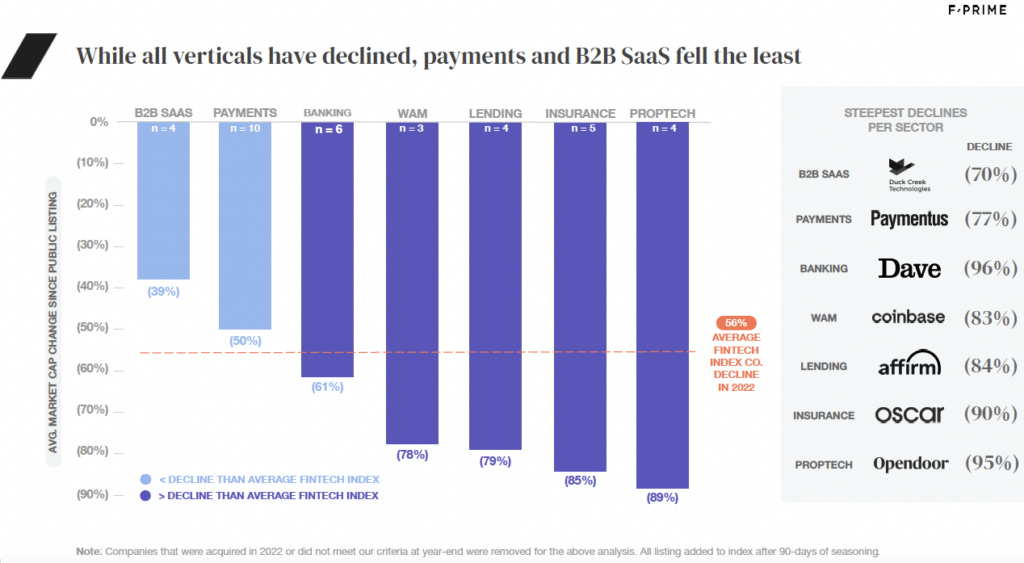

However, 2022 marked a turning point for venture capital in fintech. With interest rates rising and economic conditions tightening, investor appetite for high-growth, unprofitable startups declined sharply. Funding for fintech startups dropped by 34% in 2023, reflecting the broader pullback in venture capital investments.

New Strategy

This shift in sentiment has forced neobanks to rethink their strategies. Previously, digital banks operated on the assumption that capital would always be available to fund growth, allowing them to prioritize market expansion over profitability. But with capital becoming scarcer, companies have had to pivot toward more sustainable business models. Many have cut costs, streamlined operations, and focused on lending and subscription revenue to improve their unit economics.

The IPO market has also become a major test for neobanks. In December 2021, Nubank went public on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and Brazil’s B3 stock exchange, raising over $2 billion and achieving a peak valuation above $40 billion. The IPO was one of the most highly anticipated in fintech history, backed by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. Nubank introduced a unique retail investor incentive program called NuSócios, where customers were awarded Brazilian Depositary Receipts (BDRs) as a form of equity participation, a strategy borrowed from crypto-based reward models.

Other neobanks have struggled with public listings. Revolut has repeatedly delayed its IPO plans due to financial reporting issues and regulatory challenges. SoftBank, a major Revolut investor, has been reluctant to convert its preferred shares, causing additional complications for the company’s capital structure. Similarly, Monzo and Starling Bank have indicated that they may consider IPOs in the future, but neither has set a firm timeline.

Meanwhile, some neobanks have faced funding shortfalls and have been forced to shut down. Australian neobank Xinja raised $430 million but ultimately returned its banking license after failing to secure additional capital. The company’s rapid expansion had outpaced its ability to generate sustainable revenue, highlighting the risks of a venture-backed model that depends on continuous external funding.

Despite these setbacks, investor sentiment toward neobanks remains relatively strong. Surveys indicate that over 80% of customers who use neobanks would recommend them, compared to 60% for traditional banks. While profitability remains elusive for many players, some firms, such as Starling Bank and Nubank, have demonstrated that digital banking can be both scalable and financially sustainable.

Going Public

Successes

The journey from high-growth fintech startup to publicly traded company has been challenging for neobanks. While several firms have achieved multi-billion-dollar valuations in private markets, transitioning to a public listing has exposed fundamental questions about the sustainability of their business models. Unlike traditional banks, which generate stable revenue from lending and wealth management, many neobanks have relied on venture capital to subsidize growth, raising concerns about their long-term profitability.

Nubank was one of the first major neobanks to successfully go public. In December 2021, the Brazilian digital bank listed on both the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and Brazil’s B3 exchange, raising over $2 billion. The IPO was backed by major investors, including Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, which had already invested $500 million in Nubank prior to the listing. In an effort to increase customer engagement and financial literacy, Nubank introduced a unique retail investor program called NuSócios, which distributed Brazilian Depositary Receipts (BDRs) to eligible customers, allowing them to own a fractional share of the company.

Setbacks

Revolut, another high-profile neobank, has struggled with its plans to go public. The UK-based digital bank has faced regulatory challenges, particularly in securing a UK banking license, which has delayed its IPO timeline. The Bank of England (BoE) has pressured Revolut to improve its financial reporting after significant accounting issues emerged in 2021 and 2022. Additionally, Revolut’s investor structure, which includes multiple share classes with liquidation preferences, has complicated its path to an IPO. While major investors like TCV, Tiger Global, and Ribbit Capital have agreed to simplify the company’s capital structure, SoftBank has been a key holdout, demanding additional shares in exchange for giving up its preferred status.

Other neobanks have faced more severe setbacks in public markets. Xinja, an Australian neobank, initially raised $430 million and pursued an aggressive expansion strategy. However, after failing to secure additional funding, the company was forced to return its banking license and shut down operations in late 2020. Similarly, N26, one of Europe’s most prominent digital banks, withdrew from the U.S. market in 2022, citing regulatory complexity and profitability concerns. The company had previously expressed interest in going public but has since refocused on strengthening its European business.

In the U.S., Chime has been one of the most anticipated neobank IPOs. The company, which had over 12 million users in 2021, was reportedly targeting a $30 billion valuation for its public listing. However, worsening market conditions and declining fintech valuations led Chime to delay its IPO, opting to focus on profitability before revisiting public market plans.

Starling Bank, one of the more financially stable digital banks in the UK, has taken a different approach. Unlike many of its peers, Starling has prioritized profitability before expansion, achieving its first full-year profit in 2021. The company has raised over $477 million to date and has been working with Rothschild to prepare for an IPO. Starling’s strategy has been to focus on SME lending and government-backed loans, which provide more stable revenue streams compared to the interchange-fee-heavy models of other neobanks.

The broader market for fintech IPOs has cooled significantly since 2021. Rising interest rates and declining investor appetite for high-growth but unprofitable companies have forced many fintech firms to reconsider their timelines for going public. The post-IPO performance of other fintechs, including Robinhood and SoFi, has also dampened enthusiasm. Both companies experienced sharp declines in their stock prices after listing, reinforcing the skepticism surrounding digital banking models that lack diversified revenue streams.

Ongoing Challenges

Regulation

Despite their rapid growth, neobanks face significant challenges that threaten their long-term sustainability. From regulatory hurdles to high customer acquisition costs, digital banks must navigate a complex financial landscape while proving that their business models can stand the test of time.

One of the biggest obstacles neobanks face is regulatory scrutiny. Unlike traditional banks, which have long-established compliance structures, many digital banks have struggled to meet the stringent requirements imposed by financial regulators. In the UK, Revolut has spent over two years attempting to secure a banking license, with the Bank of England delaying approval due to concerns over the company’s financial reporting and compliance systems. In the United States, neobanks that operate under Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS) models have faced increased oversight from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), which have raised concerns about risk management and anti-money laundering (AML) protocols.

Several neobanks have already been forced to shut down due to regulatory and financial pressures. Xinja, an Australian neobank, returned its banking license in 2020 after failing to secure additional funding, despite raising $430 million. Similarly, Azlo, a U.S.-based small business neobank, was shut down by its parent company BBVA in 2021, and N26 withdrew from the U.S. market, citing the complexities of regulatory compliance. These exits highlight the fragility of many neobank models, particularly in jurisdictions with stringent banking laws.

Beyond regulation, the economics of customer acquisition remain a significant challenge. Unlike traditional banks, which benefit from deep-rooted customer relationships and broad distribution networks, neobanks must rely heavily on digital marketing to acquire users. The cost of acquiring a new customer can range from $12 to $30 per user, depending on the market. For neobanks that offer fee-free accounts with no minimum balance requirements, recouping these costs can take years.

Fraud

Fraud and cybersecurity concerns have also become growing issues. Many digital banks have struggled with identity verification and fraud prevention, with criminals exploiting weaknesses in neobank onboarding systems. Revolut, for example, faced criticism after it failed to block over £1.7 million in suspicious transactions flagged by the UK’s National Crime Agency. In the United States, Beam Financial collapsed after a Federal Trade Commission (FTC) investigation found that customers were unable to access their deposits due to operational failures.

Another major issue is the path to profitability. While some neobanks, such as Starling Bank and Nubank, have achieved profitability, most digital banks continue to operate at a loss. Monzo, for instance, reported a $124 million loss in 2023 despite growing its customer base, and many neobanks struggle to generate sustainable revenue without relying on venture capital funding. The shift in investor sentiment since 2022 has made it harder for unprofitable neobanks to raise funds, forcing them to reassess their business strategies.

Competition

Finally, competition from traditional banks and other fintech companies has intensified. Many legacy banks have launched their own digital-first offerings, replicating the core features of neobanks while leveraging their existing customer bases. At the same time, fintech giants such as PayPal, Square, and Apple have expanded their financial services, further eroding the competitive advantage of neobanks.

Looking forward, the most successful neobanks will be those that can navigate regulatory challenges, build sustainable revenue streams, and differentiate themselves in an increasingly crowded market. The industry is moving beyond the era of free banking and rapid expansion, entering a phase where financial discipline and operational resilience will determine which players survive.

Differences by Country

The neobank landscape varies significantly across regions due to differences in regulatory frameworks, consumer behavior, and market maturity. While the core appeal of digital banking remains the same—low fees, mobile-first experiences, and accessibility—the strategies that neobanks use to succeed differ depending on the market conditions in each country.

United States: High Interchange Fees, Regulatory Complexity

The U.S. neobank market is shaped by its fragmented banking system and high interchange fee structure. Unlike Europe, where interchange fees are capped at 0.2%–0.3%, smaller U.S. banks (those with assets under $10 billion) can charge up to 1.5% per transaction under the Durbin Amendment. This regulatory carve-out has enabled neobanks like Chime and Varo to generate substantial revenue from card transactions without needing to rely on lending.

However, the lack of a universal fintech charter in the U.S. has made it difficult for digital banks to scale. Most neobanks partner with Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS) providers such as Bancorp Bank or Sutton Bank to operate, rather than securing their own banking licenses. This arrangement allows them to bypass some regulatory hurdles but also limits their ability to offer full-service banking products like lending and deposit insurance. In contrast, Varo Bank became the first U.S. neobank to obtain a national banking charter in 2020, giving it more control over its operations.

United Kingdom: A Supportive Regulatory Environment

The UK has been one of the most fertile grounds for neobanks, thanks to progressive fintech regulations and a well-defined path for digital banking licenses. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has encouraged competition, leading to the rise of Monzo, Starling Bank, and Revolut, all of which obtained banking licenses within their first few years of operation.

Unlike in the U.S., UK neobanks are more diversified in their revenue models. Starling Bank, for example, has built a profitable lending business, generating a significant portion of its income from SME loans and overdrafts. Monzo, on the other hand, has focused on consumer banking, leveraging premium accounts and new investment products in partnership with BlackRock.

Despite strong growth, UK neobanks have faced challenges. Revolut, the largest digital bank in the UK, has struggled to secure a full banking license from the Bank of England due to concerns about its financial reporting and compliance controls. Meanwhile, N26 withdrew from the UK market in 2020, citing post-Brexit regulatory complexities.

Europe: PSD2 and Open Banking Advantages

The European Union’s Payment Services Directive 2 (PSD2) has been a game-changer for fintech, requiring traditional banks to open their APIs to third-party financial service providers. This has allowed European neobanks like N26 and Bunq to scale rapidly across multiple countries. However, tight restrictions on interchange fees have made it difficult for European neobanks to rely solely on transaction revenue.

To compensate, many European digital banks have leaned into subscription-based business models. N26 offers N26 Smart, N26 You, and N26 Metal, with premium features that include travel insurance, airport lounge access, and exclusive customer support. Revolut has taken a similar approach, with 30% of its revenue now coming from paid accounts.

Latin America: Financial Inclusion and Credit Expansion

Latin America’s neobank market is driven by financial inclusion, with millions of consumers previously lacking access to traditional banking services. Nubank, the largest neobank in the region, has grown to over 84 million customers, capturing 14% of the Brazilian retail banking market. Unlike its counterparts in the U.S. and Europe, Nubank has built a strong lending business from the start, issuing credit cards and personal loans to a previously underserved population.

The success of Nubank has inspired other digital banks in Latin America, such as Ualá in Argentina and Albo in Mexico, both of which have rapidly expanded their customer bases. The region’s fintech ecosystem has also benefited from government-backed digital payment initiatives, such as Brazil’s PIX system, which enables instant money transfers between banks and fintechs.

Asia: Super-Apps and Tech Giants

Neobanking in Asia is largely dominated by tech conglomerates rather than standalone fintech startups. Companies like Alibaba (Ant Group), Tencent (WeChat Pay), and Grab have integrated financial services into their existing platforms, offering everything from banking and lending to investment products.

Regulatory environments vary widely across the region. Singapore and Hong Kong have actively issued digital banking licenses, allowing new players like GrabBank and WeLab Bank to operate with full banking privileges. Meanwhile, India has taken a more restrictive approach, with most digital banking services being operated by traditional banks rather than independent fintechs.

Australia: Market Exits and Consolidation

Australia initially saw a wave of neobank launches, but many have struggled to survive. Xinja, one of the most well-known Australian neobanks, raised $430 million but was forced to return its banking license and shut down in 2020 after failing to generate sustainable revenue. Similarly, Volt Bank ceased operations in 2022, citing difficulties in raising additional funding.

The Australian market remains highly competitive, with major banks aggressively investing in digital services to compete with fintechs. Some neobanks have pivoted toward Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS) models, helping other companies integrate financial services rather than competing directly with legacy banks.

Africa: Mobile Money Over Neobanks

Unlike other regions, Africa’s fintech revolution has been driven more by mobile money platforms than traditional neobanks. M-Pesa, operated by Safaricom in Kenya, is the dominant digital financial service, with over 50 million active users. Rather than offering full banking services, most African fintechs focus on payments, remittances, and micro-lending.

However, new digital banks such as TymeBank in South Africa and Kuda in Nigeria are beginning to gain traction. These companies have positioned themselves as low-cost alternatives to traditional banks, often targeting gig workers and small business owners. As smartphone penetration and internet access improve, the neobanking sector in Africa is expected to grow, though it will likely remain distinct from the models seen in North America and Europe.

Interaction with Fintech, Crypto, AI, and Other Technologies

Neobanks are not isolated players in financial services. Their success and evolution are deeply intertwined with broader fintech developments, particularly in embedded finance, cryptocurrency, artificial intelligence (AI), and decentralized finance (DeFi). As digital banking continues to expand, neobanks are increasingly integrating these technologies to enhance customer experiences, improve operational efficiency, and differentiate themselves in a competitive landscape.

Embedded Finance and Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS)

One of the most important intersections between neobanks and fintech is embedded finance—the integration of financial services within non-financial platforms. Companies like Mesh are leading this transformation by creating API-driven platforms that connect neobanks with brokerage accounts, crypto wallets, and payments infrastructure. This allows consumers to manage multiple financial products in one interface, effectively blurring the lines between banking, investing, and payments.

Neobanks are also leveraging Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS) models to scale their services without directly holding banking licenses. Synctera, a BaaS provider, recently raised $33 million to expand its platform, allowing fintech startups to offer banking services without needing their own charter. BaaS providers act as intermediaries between fintech startups and chartered banks, streamlining the regulatory and operational complexity of offering financial products.

Cryptocurrency and Digital Assets

Many neobanks have integrated cryptocurrency trading, custody, and payments into their platforms. Revolut, for example, offers crypto trading for over 30 digital assets, while Monzo and N26 have cautiously explored crypto features despite regulatory concerns. Some digital banks, such as hi, have built entire ecosystems around crypto, offering fee-free fiat top-ups, digital asset trading, and blockchain-based payment networks.

However, the collapse of FTX and other crypto lenders in 2022 exposed vulnerabilities in the integration of crypto and banking. Silvergate Bank, a major crypto-friendly bank, saw its stock price collapse by over 85% following the FTX crash, leading to increased regulatory scrutiny of banks that engage with digital assets. This has caused many neobanks to reassess their exposure to crypto, with some, like Starling Bank, temporarily blocking deposits to crypto exchanges before later reversing the decision.

Despite regulatory setbacks, demand for crypto-integrated banking remains strong. Fintech companies like Kyash in Japan have raised significant funding to build mobile-first banking platforms that support digital assets and Web3 applications.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Personalization

AI is transforming neobanks by enabling better customer service, fraud detection, and financial recommendations. Some digital banks have developed AI-driven financial assistants to help users manage spending and investments. For example, Dave, a U.S. neobank, launched "DaveGPT," an AI chatbot that resolves nearly 90% of customer inquiries using OpenAI's technology.

The adoption of AI is not limited to chatbots. Mastercard's Chief Information Officer, Ken Moore, stated that AI is expected to become integral to all banking processes within the next 12 months, impacting customer service, fraud detection, financial advising, and marketing. Meanwhile, traditional banks like JPMorgan and Bank of America have launched AI-powered virtual assistants to compete with fintech offerings.

Neobanks are also using AI to enhance security and compliance. Airwallex, a global fintech, has deployed AI-driven Know-Your-Customer (KYC) systems that reduce false positives by 50%, improving onboarding efficiency for digital banks.

Decentralized Finance (DeFi) and the Future of Neobanks

Some neobanks are exploring the intersection between traditional finance (TradFi) and DeFi, allowing customers to access yield-bearing crypto products, tokenized assets, and decentralized lending protocols. However, regulatory uncertainty remains a major hurdle. Regulators are increasingly scrutinizing fintechs that blur the line between DeFi and traditional banking. In the UK, financial authorities have imposed stricter compliance requirements on neobanks engaging with crypto, requiring them to maintain extensive records on customer transactions.

What Comes Next?

Neobanks have fundamentally changed the financial industry. Traditional banks, once slow to innovate, have been forced to adapt. Many have launched their own digital-first brands, partnered with fintech companies, or acquired challenger banks outright.

Yet the road ahead for neobanks remains uncertain. Regulatory scrutiny is increasing, particularly in the U.S. and Europe, where authorities are taking a closer look at anti-money laundering compliance and risk management. The business model question remains unresolved—will subscription tiers and lending be enough to sustain neobanks, or will many eventually be absorbed by larger financial institutions?

One thing is clear: the era of rapid, venture-backed expansion is over. The survivors will be those that can evolve beyond the free banking model, build diversified revenue streams, and navigate the increasingly complex regulatory landscape. Neobanks are not going away, but their future will look very different from their past.

Whether they become true banking giants or remain niche players in a financial system still dominated by legacy institutions remains to be seen. The promise of disruption was real—but the challenge of sustaining it is greater than many had anticipated.

Excellent analysis! Meanwhile, the Trump developments regarding the MAJOR disruption of the CFPB and his anti-regulatory stance, suggest a positive shift in the optimism of lenders , banks, credit unions… My industry, subprime lending for the -60% of USA households living paycheck to paycheck, and the ~40% of households earning >$100K annually living paycheck to paycheck is salivating over the prospect of less regulatory and compliance expenses! Hopefully, >unemployment won’t increase loan defaults dramatically! We shall see.

Bybit > Neobanks