Hi Fintech Architects,

Welcome back to our podcast series! For those that want to subscribe in your app of choice, you can now find us at Apple, Spotify, or on RSS.

In this conversation, we chat with Libor Michalek - President at Affirm. Libor oversees engineering, risk, operations, product and design. He previously served as Affirm's President of Technology and Chief Technology Officer. Prior to joining Affirm, Libor was an Engineering Director at YouTube and Google where he was responsible for Application Infrastructure & Site Reliability Engineering across multiple sites. During this tenure, YouTube tripled in page views, hours of video watched and revenue.

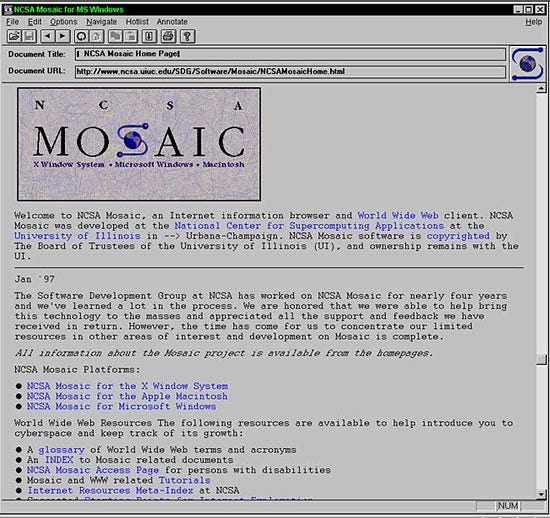

Earlier in his career, Libor was the Chief Technology Officer of Slide, a personal media-sharing service, which was acquired by Google in 2010. Libor also served in software architecture and management positions at Topspin (acquired by Cisco), Egroups.com (acquired by Yahoo!), Talarian (acquired by Tibco), Thinking Machines Corporation and the National Center for Supercomputing Applications.

Libor earned his B.S. in Computer Science from University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Topics: fintech, buy now pay later, BNPL, e-commerce, machine learning, loans, credit, credit cards, payments

Tags: Affirm, Thinking Machines Corporation, PayPal, Amazon

👑See related coverage👑

Fintech: Fintech: How can Robinhood afford 3% cash back on its new credit card?

[PREMIUM]: Long Take: Plaid's payments ecosystem & Affirm's decoupled debit card reveal embedded finance Trojan Horse

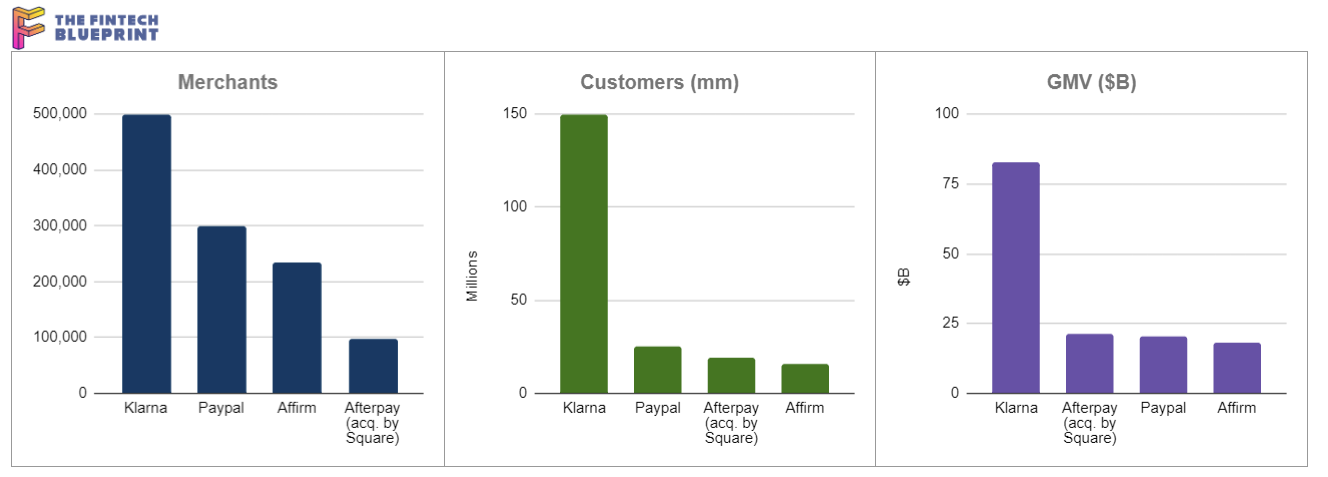

[PREMIUM]: Financial Analysis: Can Affirm beat Klarna in the BNPL market?

Timestamp

1’00: Internet Pioneers and Business Innovation: Libor Michalek touches on Early Web Experiences

4’56: Digital Transformation and Commerce: Unpacking the Consumer Insights and Technological Advances That Fuelled the E-commerce Explosion

9’18: Beyond Traditional Finance: How Affirm's Founding Insights and Technological Integration Redefined Fintech in the 2010s

13’14: Redefining Credit: Exploring the Consumer Demand for Transparency and Fairness in Financial Products with Affirm

19’04: Integrating Innovation: How Affirm's Unique Approach to E-commerce and Payments Shaped Its Market Strategy

23’47: Machine Learning and Financial Innovation: Launching Affirm's Transaction-Specific Underwriting Models

27’56: Assessing Investment Opportunities: The Risk and Return Profile of Affirm's Customer Loans from an Institutional Perspective

32’11: Empowering Customers: Affirm's Commitment to Transparency and Support in Financial Services

37’42: Leading the Charge: Navigating Competition and Innovation in the Buy Now, Pay Later Market

41’22: Defining Innovation in FinTech: Distinguishing Between Technology-Driven and Finance-First Companies

43’29: The channels used to connect with Libor & learn more about Affirm

Illustrated Transcript

Lex Sokolin:

Hi everybody, and welcome to today's conversation. We are very lucky to have with us today Libor Michalek who is the president of Affirm, and of course Affirm is the category defining BNPL company, but there is so much more to what they've done and accomplished. So, I'm really excited to jump into it. Libor, welcome to the conversation.

Libor Michalek:

Thank you, Lex, really appreciate you having me here today, and I'm looking forward to the conversation.

Lex Sokolin:

I want to rewind back to your definitional experiences with the internet. Broadly speaking, what were your first moments interacting with the web, building for it, understanding its culture? How did you come into that space?

Libor Michalek:

I got my CS degree from the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana in the early '90s. So, I was going to school there while Mosaic, the proto browser, the first browser was being written and developed at NCSA, the National Center for Supercomputing Applications and I also happened to work as a student programmer there. And so, I got to see it being developed. When I got to school in 1991, FTP, Gopher, email, Usenet were all provided to us as students, and we had access, and it was pretty exciting. And during those four years, right around '93 is when the first browser, when Mark and his team developed the first browser there and really as students, as people who had access to it, we were the beta testers, and it obviously took off quite quickly. And so, I can still remember going to a movie with my friends, all my CS and NCSA friends, and for the first time seeing a URL in an ad at a movie theater out in the wild. And it was like, "Whoa, I think this thing's going to be big." And sure enough.

Lex Sokolin:

I remember there was a moment in the middle of the two thousands when stores would just print out a Twitter logo and put it on their window and I'm like, "Why? What are you trying to do with it?" But the URL in the movie, I understand. So, what was the internet for at the time that you saw it emerging? How did you think about its purpose?

Libor Michalek:

Its purpose even then was, it was two-fold. It was getting access to resources that you didn't have, and so having access to computers and equipment for running large computations, for experimental computations for different types of computer architectures. So as a CS student, it was really being able to have access to these things without having to be physically there. And that was pretty exciting. And the second piece was information, even then, even pre-web, it really was about either finding the right person or the right piece of information to understand a specific topic. And so that kind of nascent remote access and access to information were already there even before the browser.

Lex Sokolin:

Are those the types of early companies where you spent the first part of your career, like the architecture for information?

Libor Michalek:

It was more compute and system design. So, I think the first few companies, first few startups I worked on, one was a supercomputer manufacturer Thinking Machines Corporation. One was a software developer toolkit for building distributed systems, a company called Talarian. One was a hardware company, which was the first generation of InfiniBand gear, which is data center networking gear, which we sold to Cisco. And then I started to transition more up the stack to consumer products and consumer use cases from that kind of early, what I would call, pure engineering roles.

Lex Sokolin:

Can you paint the picture of how those consumer use cases emerged or culturally, what was the insight that led to the explosion of media and information, and on the infrastructure side, was there anything that unlocked that?

Libor Michalek:

I mean the insights on the consumer side, consumer perspective, it really was to help organize and access that information and connect people. So even the early companies, Yahoo started out as a directory to the web and then AltaVista to help search the web, we're growing in parallel to the idea of connecting people. So, one of the first consumer startups I worked on was called eGroups, which really was just online email lists and it eventually got bought by Yahoo and became Yahoo Groups, but it was really about just connecting people and finding access to like-minded people in the world on any topic. And so, I think a lot of the early web was just trying to understand this rapid growth in information and of course groups, people who are producing information and so bringing them together and that really was kind of where that initial growth came from. And then of course e-commerce and then access through the web to physical goods and how to connect people to the things that they want as well. That was really where things were going really early on.

Lex Sokolin:

Was that transition from information and connecting the nodes in a network, whether those are people or businesses, and that transition from the media experience or the connectivity towards exchange and commerce and economic activity, was that obvious from the beginning or was there any sort of step change that you saw that showed commerce becoming a much more important use case? Of course, Amazon is sort of the poster child, but were there other symptoms that made it more and more relevant for you?

Libor Michalek:

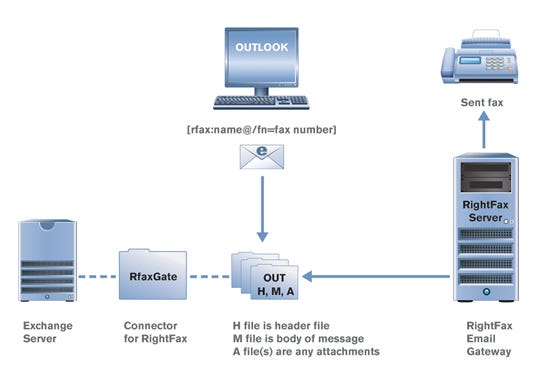

I would say it was relevant pretty early on. I mean, I remember even again kind of really early in college when the web was kind of just starting when networking was a thing, somebody at school put a vending machine onto the network so you can get it to perform and then vend over the network through sending some commands to it. Somebody, there had been a business which would deliver pizza, obviously pizza delivery, but you could fax them. And so right away somebody did an email to fax Gateway so you could use email to order pizza.

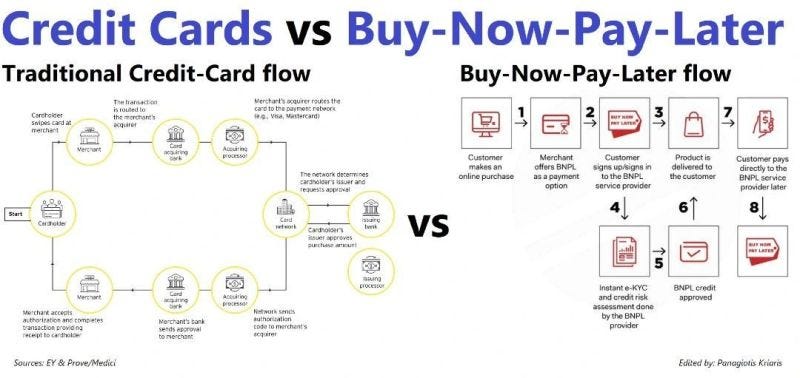

And so, I think the connection to commerce was pretty quick and Amazon started pretty early in the history of the web, I think as a recognition of that. I think a lot of the acceleration was making that more accessible and natural to a much broader audience. And I think that's really where the commerce came from is just making it more accessible and easier. And so, in some ways, when we think about, and we built Affirm, it was really the convergence of a number of technologies, but two of the ones that were important coming together was e-commerce and mobile. Just having that mobile device, having access to the internet to the world through your mobile device just made purchasing and shopping and just access to commerce over the internet feel much more natural and a thing that people were very comfortable doing because it was in their pocket because it was accessible all the time.

Lex Sokolin:

You're on the other side of the fear of people using credit cards online, you're past the initiation of FinTech with Mint and people sharing their bank accounts and you're in the middle of the 2010s where you already have quite a bit of FinTech activity, but it's still very splintered. Most of it is just, "Hey, the Internet's a distribution channel, let's put some financial products online and then we can sell financial products in a new place." But Affirm does something quite different and is much more integrated with the core of the internet. So maybe if you could expand on that in that moment at the founding of the company, what were the core insights that you had or maybe your core hypotheses that gave you the courage to do it?

Libor Michalek:

It was sort of this, from a company founding perspective, it was two-fold. It was the idea of what is, the company mission is building honest financial products that improve people's lives, and so the idea of what that looks like. And the idea was largely around a financial product, a credit product, unlike a credit card, that was aligned with the interest of the consumer. So, when the consumer got what they were looking for, we would give them all the information that they needed to make a decision and they headed a priori for making a purchase, that they would have that, and it wouldn't change on them. It was like, "Here's what you're going to pay, here's the all-in cost because you're going to pay overtime and you can decide here whether this is what you want or don't." And we win when the customer wins and we share in the negative outcome if there's a negative outcome because they can't repay us.

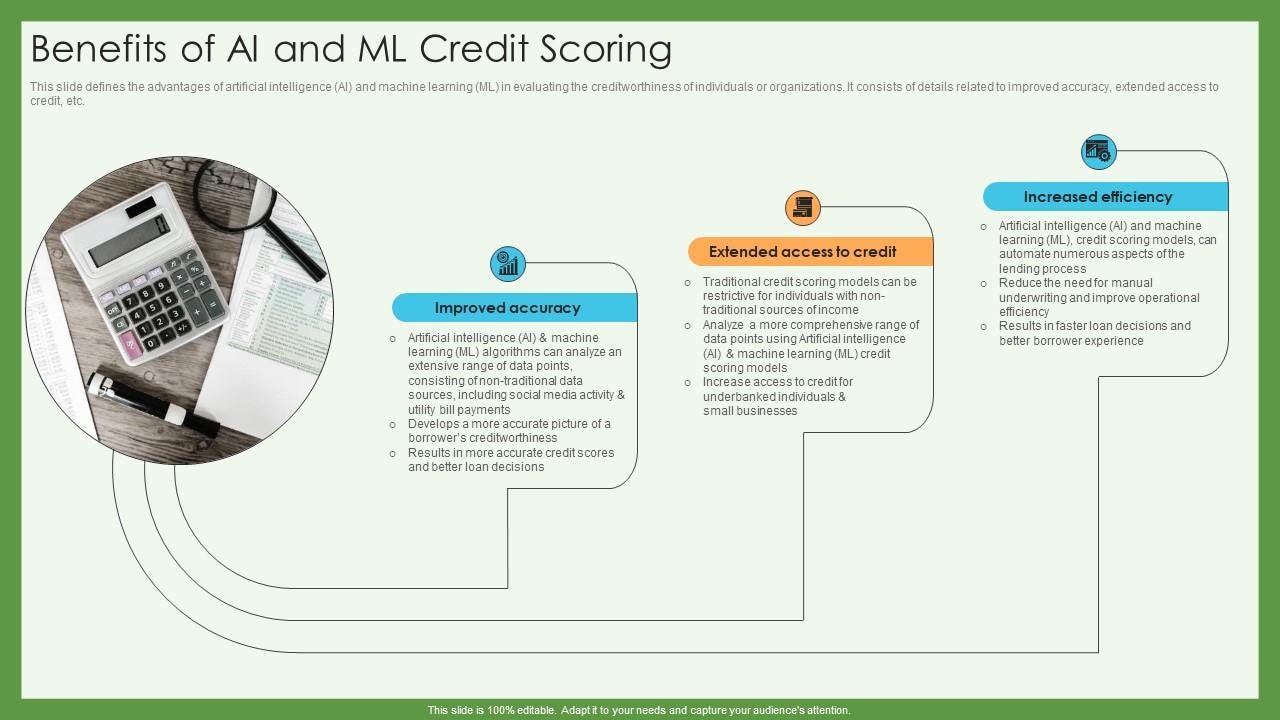

And that was the idea, the technological genesis for it of why did we think that idea made sense to build then at that time and thought that we could make it successful was the convergence of a number of technologies. I mentioned two of them, e-commerce who had become normalized. Everybody had a mobile device in their pocket, so they had access to e-commerce, but also their personal information and their identity in a certain sense through their phone. And then two more technologies, really the rise of machine learning and being able to build large models that can, large predictive models trained on large amounts of data but be able to make real-time decisions as well as access in real-time to consumer information, third-party consumer information that could be accessed right away. Credit reports is the most obvious, but other pieces of information as well about the consumer.

And so those four pieces that they all existed as capabilities we could draw on really made us feel like, "Okay, we can build this product. We can do real-time underwriting, real-time pricing, deliver it in a form factor that is understandable to the consumer and easy to understand and relevant in the moment as they're purchasing." And that really brought it together.

And from my perspective as an engineer, it was the first time I actually got excited about, or frankly interested in finance because it was the time I saw it as a technology company, as a technology-driven idea where the idea could not exist without those capabilities, those technologies sitting at the core and us developing them further to deliver a product which couldn't exist without it. So, like you said, we went from selling things that existed in the real world and things that have existed for decades and just selling them on the internet and that wasn't particularly interesting. It was interesting where it was like, "Okay, we could actually build a product that's better for customers than their credit cards, and we can only do it because this technology exists here and now," that's when I got excited by the idea and decided to build this company.

Lex Sokolin:

So if we explore the negative space of the other options that people had at the moment, walk me through the consumer's mindset and their willingness to pay and what it is that they're really solving for. We know the solution that has taken up the space and defined an industry being underwriting each purchase, but from a consumer perspective at the time, what is it that people were doing and had in their commerce experience that was not transparent that they were struggling with that you thought there'd be a willingness to pay and sort of a willingness to adopt?

Libor Michalek:

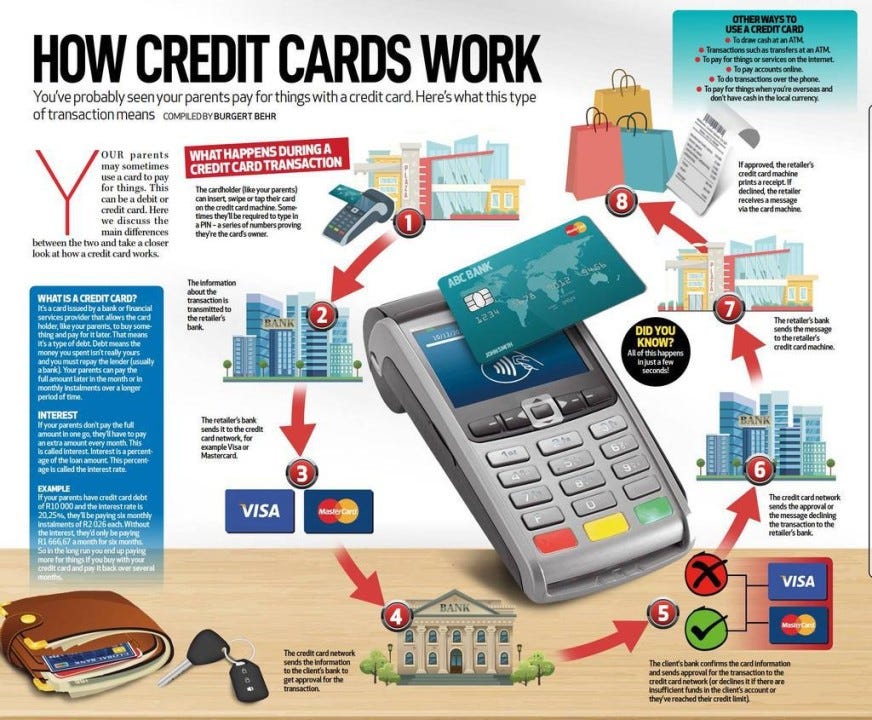

Yeah, I think there's two major components to it, and one is sort of the background, what I would call the background understanding of how credit cards work, and so that existed over a period of time. And by that, I mean the credit card sells you convenience and ubiquity, but it actually makes money when the unexpected or unwanted happens. When everything's happy, you swipe here, you swipe there and you pay it off at the end of the month and then rinse, lather, repeat. But the actual revenue and all the incentives are around when you miss that payment and either because of, for whatever circumstance, whether it's negligence or you really are in financial distress, whatever the reason, that's when suddenly the thing you bought costs more than you had planned to pay for it because you're now getting all these fees and interest charges on top of it. And of course, that's where the industry makes all of its money.

So, I think there's recognition whether conscious or subconscious exists in the consumer that this is a tool that they like, but it can definitely bite them, and that's really where the companies that provide it to them are deriving value. And so, when we decided to build a product that turned that on its head, I think customers really gravitated to the idea that just like purchasing anything, when you have the full purchase price in front of you, that decision is much clearer and much more comfortable. And so, one of the things customers tell us even to this day is that the product gives them confidence that they know what they're getting, they know whether they can or can't afford it with the all in cost of what is this really going to cost me?

And of course, customers have always recognized that there is a place in their life for credit, a sofa today is worth more than a sofa a year from now. And when you can put a price on that value and tell the customer, "Hey, it's going to cost you another $80 to have this thing today versus a year from now," the customer can make a rational choice and they know that that's what they're going to pay. So that's a big part of it. And of course, or I shouldn't say of course, but I also believe that some of that was brought to the forefront, some of that anxiety and looking for a solution was brought to the forefront in customer's minds from the financial shock in the late Aughts, 2008, 2009 and what was happening with credit and with people's finances at that time. And so, part of that I think was just this in the background understanding how credit cards work and part of that was kind of the shock of sudden change in the credit market and people's finances.

Lex Sokolin:

What was the first version of the technology that you built? What was the embarrassing first V.1 that you launched with?

Libor Michalek:

It was definitely quite a bit of iteration. At one point in the very early versions, we were even exploring with the idea of just doing the underwriting and reselling it as a technology. So as a bunch of engineers, Max is an engineer, I'm an engineer, a group of engineers together we're like, "Well, let's build infrastructure and resell it to people who already have the consumer brands and talk to customers all the time." And that was a little bit embarrassing in hindsight in the sense that we went, and we talked to people and everybody basically said, "Well, if this technology is so great, why don't you put your own money at risk? Why are you selling this thing? How do we trust it with our money if you don't trust it with your own money?" And so that was very much a, "Oh, they're right. Let's go do that. Let's go prove it out." And so that was a little bit embarrassing to have something so obvious told to us by so many people before we actually went and started doing that.

And then the first one, the first merchant, there was a number we were talking to, but the early version of the product was just very simple, very short term. I think it was like a 30-day product where you purchase and then owed the full amount in 30 days, and it was 1-800-FLOWERS. We were selling flowers and making that easier, so that was pretty fun. But then we pretty quickly figured out, "Okay, people need to be able to pay over more time, over more installments and really start to build that out and realize that durable goods and larger purchases were really where it was at. And so, I think Casper was one of our very early merchants that came next, and then from there it was like, "Oh, okay, we think we understand where this thing really has value for customers," and it picked up from there pretty quickly.

Lex Sokolin:

I think in addition to the consumer product innovation, the company also has a really different shape on the go-to-market motion than a credit card company or a lender that's kind of just indifferent about where it's accepted, and it just integrates into some other payment processors and that's the end. Whereas, for you, there's definitely an underwriting component, but there's also an e-commerce like integrating into the shopping cart component, there is a payments element to it with interchange, there is a direct-to-consumer experience. Was there a sequencing to building out these different sides of the network and how did you discover and pace your development in each of these?

Libor Michalek:

We pretty early on made a conscious decision and conscious effort to be vertically integrated to really focus on the full stack, from being directly integrated with the merchants including how we're promoted on the merchant site all the way through obviously underwriting, but then also the capital markets components, the servicing components, the customer support, and how the customer interacts with us around repayment. And we thought about it as, "Okay, we will vertically integrate, we will have data and access to information, but also efficiencies through that whole journey, and then we will invest in expanding outward." And so, it was a sort of depth first approach and with breadth second, that was sort of the traversal mental model that we approached it with.

And so, a lot of our efforts went into investing. We did invest obviously starting out small, small amounts in each of those in the merchant experience, in the consumer purchasing experience and the capital experience and the servicing experience. And obviously when we were small, pretty rudimentary, although then as well as now underwriting and the modeling was always an outsizing investment for us. But even when we did the modest investment, it was kind of the full stack and where we might only have one or two people working on any one of those, and then we said, to scale, we just have to continue to build those out and continue to improve and automate and iterate horizontally as we built them out for more scale for larger merchants, for more consumers. But the idea was that we would do the full stack from the get-go.

Lex Sokolin:

I'm begging the question a bit because from the outside I think it's remarkable, and I'm curious if my guess is true or not, but one of the things that you've been able to do is get integrated into the checkout experience in a way that in many ways echoes PayPal's growth. Of course, no bank or credit company has that experience of building out a payment processor that's native to the internet, and so building out a lending product that's native to the internet through e-commerce, I think is very unique and is something that very few people in the world could have done. Were you inspired by Max's prior experience with PayPal? Was there a rhyme to thinking about the payments part of it and that knowledge of how the checkout works or did that follow from starting with the credit products?

Libor Michalek:

No, there was definitely a rhyme. I mean, I think the rhyme was more around the insight and motivations that it could be done, that this is something that could actually be brought to bear with effort and again, with technology and sort of that recognition of, "Oh, okay, this is actually possible now given these foundational technologies that exist, let's bring them together and let's not be afraid that it might not work." Where instead of building one component and then trying to figure out how to fit it into the horizontal layer cake that is payments, we decide to say, actually that is a recipe for frustration and slowness, let's just build the whole thing and maybe make it pretty rudimentary in each of the specific instances and then let's go directly to the merchants and have those conversations. And so, I think it was sort of both the audacity of saying, "Well, let's do it all," while at the same time a little bit of fearlessness of saying, "But that's okay. There's no reason this shouldn't exist, and it shouldn't be possible, so let's try it."

Lex Sokolin:

How did you start working on the machine learning models for the underwriting? There's no credit card that can underwrite every single transaction, which is what you're doing here, and only with the advent of mobile devices can you have proximity payments in a way where you're bringing an intelligent computer to every single transaction, but how did you think about starting out on that journey?

Libor Michalek:

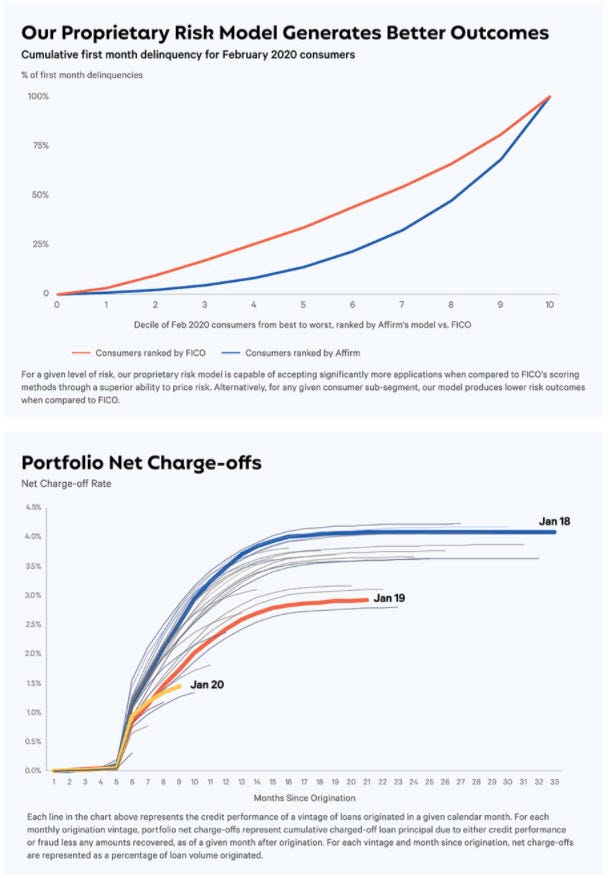

So Max obviously worked at PayPal, one of the areas he personally was pretty passionate about was fraud. Nathan Gettings who also worked at PayPal under Max very much understood fraud and fraud modeling. He, after PayPal, became the CTO of Palantir and then was one of our founders as well and was at Affirm for the first few years. They really had experience in that fraud modeling and so really decided, well decided, "Hey, let's supply this modeling, which has been working pretty well at fraud and which we still do to this day, let's also try applying it to credit and over a longer time period, this idea of repayment."

And it was very much an iterative process and that was part of it as well in the sense that early on the modeling was okay, we ran it in parallel to basically just rules-based decisioning and we're iterating on making it the live model. But we early on, luckily the company was small, but we also lost quite a decent amount intentionally just to put a bunch of loans out into the world, see how they performed, and then gather data on the performance as well as data we were getting about those consumers and their finances primarily and really understand how that interacted and just iterated, iterated, iterated the modeling and steadily improved the delinquency outcomes that we were getting.

Lex Sokolin:

Was it difficult to tell the FinTech story in the beginning, especially if you needed capital to build the business, but then you needed capital to underwrite and lose money until the machine learned better? How did you package that story to probably investors that didn't understand it yet?

Libor Michalek:

Yes and no. I mean, yes, it's definitely a hard story to tell but that is what startups are about and venture funding and we had some early... Our early venture funding was really great, Lightspeed was a fantastic investor, Khosla and a few others. They understood what it takes to build a company that hadn't been done before and what that looked like. And so that was where the original money was coming from.

By the time we got to a size where we're like, "Okay, we're getting to a point where we need to raise real capital funding from real people that are in the business of providing warehouse lines for things like what we're doing," by that point, we'd gotten enough iterations on our models, enough performance data to be able to tell that story. And Jefferies was our first partner there, but they certainly covered their risk with what they were charging us. So, I think they were definitely like, "Ah, okay, we see the data, this looks pretty good, but we're going to make sure we're not left holding the bag." And I think in retrospect they feel pretty good about what they got out of it. I hope they do.

Lex Sokolin:

Yeah, it sounds the opposite experience from Goldman Sachs and Apple. The lesson there is don't negotiate platform fees with Apple.

Libor Michalek:

That sounds reasonable. That sounds like pretty reasonable advice.

Lex Sokolin:

The only folks who can do it I think are the American courts and the Department of Justice. Looking forward to that one. Let's double click on that point around the financial asset. And from an asset class perspective, if now I'm Jefferies or if I'm an institutional investor and I'm in the job of running some fixed income fund, what does exposure to a firm's customers look like? Can you characterize on a population level the riskiness of it, the return profile for an institutional investor, anything you can share about that side of it?

Libor Michalek:

There's a couple of things about it, actually, there's a few things about it that I believe that our institutional investors really appreciate. I think the fact that it's short-term lending therefore means the weighted average life of the outstanding balance is pretty short. I mean, I think for us it's on the order of four and a half months, last time I looked. So, four and a half months, you're turning over a lot of loans, a lot of collateral pretty quickly. So, your exposure and your ability to change what you're doing as it relates to the macro environment can change pretty quickly when you have that kind of weighted average life. So that's one piece.

The second piece is the purchases are small, and so you can get a pretty robust blend into whatever portfolio you're trying to build of different type of users, different user profiles. And so, you've got this small amount, quick turnover, it really allows you to blend together very specific outcomes. And then when you look at the customer base, we really do have a broad swath of customers, the full FICO range and with a lot of spread between how your best customers are performing from a credit perspective as you get into the more challenged areas. And then that again lets you really put together a very specific outcome that you're looking for as an investor. And of course, we obviously help them construct what it is that needs to happen, and that's how we think about it even for the loans that we hold on ourselves is really managing it through that lens.

Lex Sokolin:

Do you find that there's an element of having competed on the credit card use case versus the buy now pay later use case and delivering a value proposition that people like and are choosing into, but then on the other side, from the overall exposure on the whole book, are you as a result more performant than personal loans or credit card loans in terms of the defaults and people paying on time and things like that as well?

Libor Michalek:

What we see in the data that what you're saying is accurate, it does perform better. And we talk to customers, and we look at the numbers, so we look at this qualitatively and quantitatively. There's an element to having a very clear bounded discrete loan from the customer's perspective is motivating to it being one of the things that they want to pay off first. Because as customers have told us, "If I want to get somebody... I've got five people calling because I'm not paying them, I'm going to pick the one that's going to be the fastest to get them to stop calling." And so, a lot of times they will, that will mean that they're like, "Okay, this Affirm thing, it's very specific. I know exactly what the amount is, I will just pay that down and pay it off and then move on."

And so we definitely get some of that from a behavioral aspect, but also because it is discreet and usually because it is in compared to the rest of their finances, I don't want to say small, but it's more modest in size and therefore again it sort of becomes an easier priority, it feels more, something that's more digestible for them and therefore they're motivated to make that happen. And it shows up in performance. I think also just the nature of very specific cadence of payments that does lead to the end of the loan is something that also feels very intuitive versus minimum monthly payment on a credit card can feel like it's going to be something that you're doing in perpetuity, it feels Sisyphean. And when you have an alternative which is like, "Okay, I'm just going to make six more, eight more, 10 more payments on this thing of this size," that feels much more understandable and much more tenable.

Lex Sokolin:

Well, it's certainly much more customer-centric.

Libor Michalek:

On the customer-centric point, I mean that's also one where we feel really important about why we don't charge late fees, for example, or why we don't amortize past the point of what we told you we were going to charge you an interest even if you're late, even if you get slowed down, because that's part of our value commitment to the customer is what you see is what it's going to cost you. And if for some reason you are having trouble, our goal isn't to make that harder for you, our goal is to actually try to figure out how to make you repay what you owe easier. And that means we offer re-amortizations, deferrals, all different ways to actually simplify that. We've looked at the data and obviously people make a lot of money off of late fees, but they don't move the needle in terms of customer performance beyond basis points or tens of basis points of delta. And from building a product that is customer-centric and delivering on that brand promise, a few tens of basis points just isn't worth it.

Lex Sokolin:

When you look at the future of the company and the extensions of that three-sided network we talked about before, the strategy with the Affirm card is really interesting as well as the extension to a consumer app where people can see all their stuff and see how it's phasing in overtime and so on. It's sort of a motion that I've seen a couple of companies do, Shopify starting in the commerce back end and then extending to its own app and so on. How do you think about that product and what's the purpose of that product?

Libor Michalek:

The purpose of the product is to be available in more places where customers shop. We want to ensure that when our customers are thinking about, how am I going to pay for this, can I afford it, that we're there, wherever there is. And so, the card is really a driver for places where we are not operating today offline and the slowness and legacy infrastructure of offline and how do we help customers there? That's a large motivator for the card, as well as of course surfaces and merchants we don't work with directly but being able to be available there.

And so, it really is about expanding the surface area of relevance for our customer base. And we see it in how customers use the product. Places where we're directly integrated and work with the merchant somewhere like Amazon customers will still use us, even our card holder customers will still use that direct integration because for them it's easier, it's smoother, it's something that they know and understand. And so even though we have a card product out in the world and a lot of customers are using it, they will go back and forth between using the card because that is the modality that is most relevant to a specific purchase, but they would go back to using the direct integrated merchant experience, because that's the one that's most relevant. So, we really think about it as increasing our surface area and not a separate thing.

Lex Sokolin:

So you're not going to be adding in a neobank and a robo-advisor and a crypto trading app and a messaging app and a social financial sharing app and a financial literacy education into there?

Libor Michalek:

Some of those sound better than others, some of them are more relevant. One of the things, the financial literacy one I think it’s actually an important one and one we talk about on a regular basis. The irony of financial apps are that the people who use them, what I would call religiously, are probably the people who need them the least. They're the most financially literate and they use them to help manage their finances. I think when we look at it, we do think financial literacy is really important. It is a non-trivial knowledge base that we want to help people tap into and understand. I think it has to be a part of the purchase experience, otherwise it doesn't feel relevant for most people, and it doesn't connect in a visceral way. And so, it is something that we're thinking about, but we actually think about it when we explore those ideas in the context of purchasing and not as a separate thing.

Lex Sokolin:

Let me ask you about the competition and the space as it's evolved from the moment of founding, you came in and defined the category in a very blue ocean strategy way, nobody was really doing this. And fast-forward almost a decade, of course, Affirm is a very large company, 600 million in revenue, a public company worth billions and billions, but at the same time, it's clearly a path that is attractive to others. And so, you see a bunch of companies coming into the space and copying the model, lots of B2B pivots of we're going to do buy now, pay later for banks and the big tech companies are in as well with Apple trying to create its own products, how do you make sense of folks chasing you and trying to replicate the core offering? What's the signal from that? And maybe after we'll follow up, what's your response? But what do you make of the signal?

Libor Michalek:

I think the signal is largely a validation of the concept of that this knowability and this clarity for accessing credit, and of course it's a reaffirmation that credit has a place in people's lives, an important place in how they manage their finances. And so, I think largely it's a validation of the market for us. I mean, not that we needed a ton, obviously we see it in our own numbers, but it is a reaffirmation of the, "Okay, this is a thing." And now that it's becoming something a little bit more ubiquitous and there's more understanding and there's a bidirectional between the merchants and the consumer understanding of this being a better way to access credit in a relevant way, that it's something that's here to stay and is going to matter. And so, I think that part is definitely encouraging.

Lex Sokolin:

So how do you navigate that simultaneous expansion of the market and then the squeezing in by a bunch of these different players? What's your approach to the competition?

Libor Michalek:

Build a better product is ultimately it. I mean, I think a lot of the competition steps into it or has stepped into it with short duration, small amount purchases and the underwriting and the complexity of managing, ultimately lending, really gets exponentially more complicated as that duration starts to expand, as the amounts go up, as you layer in interest in a lot of cases, to actually be able to pay for those costs of funds and manage that risk, I think it gets quickly more complicated.

And so, from our perspective, it is making sure that we continue to build out the product in a way that is relevant to a larger swath of users, a larger share of merchants, and especially a larger share of transactions where people might want to access credit to be able to make those purchases. And so in that sense, we talked about, we started out going very vertical and building out those capabilities, now it is really going wide and covering as much breadth as possible, and we see the competitors having trouble doing that, because it is a large investment and one we've made over the last decade of how do you manage on the capital side, on the risk side, on the fraud side, those kinds of purchases in a way that still feels light and accessible to a wide range of customers.

Lex Sokolin:

We're coming up on time, so I've got a very broad question for you, and I think it goes to the heart of sustaining advantages in FinTech and to culture and leadership, and I'm very interested in your journey. In particular, there are finance companies that want to be technology companies and there are technology companies that happen to be working on financial services, on delivering finance. What's the difference between the two from a cultural perspective, from a mission perspective, from a company building perspective, and how would you advise others who are thinking about building in the space on the distinction between the two?

Libor Michalek:

Yeah, I think there's two parts to this. The one I touched on earlier, which is, is technology existential to what it is you're doing. Is that the thing that actually enables the product and the solution that you want to put into the market? Or is it a gloss? Is it an optimization? Is it an efficiency gain? If it is just the latter, it's technology in service of finance. If it's actually something that can only exist because of the technology, then I would say it's a true technology company.

The other piece though, to your point about leadership and technology companies, I think it's important to recognize, and I say this to the team a lot, is that technology is not just software or software and hardware, it is the process by which you build. And it is the feedback loop and the iteration on that feedback loop between people who build software, domain experts, software engineers, business experts, that they are coming together to build something, put it into the market as quickly as possible, and get feedback on how that's doing and in the process, learn more about the domain in which they are operating and then take that new knowledge and put it back into software and product and releases.

And that evergreen process of continuing to innovate, continuing to improve, continuing to learn more about the space in which you operate and having that then reflected in the software and the product and ongoing feedback really is what is technology. I think if you can buy software, that's not technology. If you are in the active process of continuing to innovate and develop and having that tight collaborative integration across your teams that is required to deliver that, that's technology.

Lex Sokolin:

Fantastic. Libor, thank you so much for joining us today. If our audience wants to learn more about Affirm or about you, where should they go?

Libor Michalek:

Affirm.com, there's more information there. They can send me an email too.

Lex Sokolin:

Everybody send him an email. Wonderful. Great to have you on the podcast.

Libor Michalek:

Thank you for having me, it was a lot of fun.

Shape Your Future

Wondering what’s shaping the future of Fintech and DeFi?

At the Fintech Blueprint, we go down the rabbit hole in the DeFi and Fintech world to help you make better investment decisions, innovate and compete in the industry.

Sign up to the Premium Fintech Blueprint newsletter and get access to:

Blueprint Short Takes, with weekly coverage of the latest Fintech and DeFi news via expert curation and in-depth analysis

Web3 Short Takes, with weekly analysis of developments in the crypto space, including digital assets, DAOs, NFTs, and institutional adoption

Full Library of Long Takes on Fintech and Web3 topics with a deep, comprehensive, and insightful analysis without shilling or marketing narratives

Digital Wealth, a weekly aggregation of digital investing, asset management, and wealthtech news

Access to Podcasts, with industry insiders along with annotated transcripts

Full Access to the Fintech Blueprint Archive, covering consumer fintech, institutional fintech, crypto/blockchain, artificial intelligence, and AR/VR

Read our Disclaimer here — this newsletter does not provide investment advice and represents solely the views and opinions of FINTECH BLUEPRINT LTD.

Want to discuss? Stop by our Discord and reach out here with questions

Share this post