Hi Fintech Architects,

Welcome back to our podcast series! For those that want to subscribe in your app of choice, you can now find us at Apple, Spotify, or on RSS.

In this conversation, we chat with Anthony Cimino - Vice President and Head of Policy at Carta, an equity management company that builds the infrastructure for innovators, supporting approximately 35,000 companies, over 2.2 million stakeholders, and more than 5,000 funds.

In his role, Anthony oversees the team charged with policy development, advocacy, and engagement to expand equity ownership and bolster private markets. Prior to joining Carta, Anthony held multiple positions, including Senior Vice President and Head of Government Affairs at The Bank Policy Institute. Anthony holds an MBA from The Carey Business School at Johns Hopkins University, as well as a Bachelors degree from UCLA.

Topics: fintech, regulation, policy, private markets, fund administration

Tags: Carta, SEC, Committee on Financial Services

👑See related coverage👑

Fintech: How can Robinhood afford 3% cash back on its new credit card?

[PREMIUM]: Long Take: Can balanced regulation for the crypto markets emerge after crash?

Timestamp

1’23: From Capitol Hill to Financial Crisis Management: Tracing Anthony's Journey through Finance and Policy

6’24: Building Trust in Turbulent Times: The Crucial Link Between Public Engagement and Policy Formation

10’50: Shaping the Future of Finance: The Essential Role of Stakeholder Engagement in Policy and Regulation

14’50: Digitizing Equity: Carta's Impact on Private Markets and the Future of Financial Infrastructure

20’07: Unlocking Private Markets: Navigating Complexity and Challenging Paternalistic Regulations

24’17: Expanding Economic Opportunity: The Imperative of Broadening Access to Private Markets

27’27: Beyond Data: Carta's Vision for Empowering Founders and Investors in the Private Market Ecosystem

31’50: Tailoring Growth: How Carta Supports Founders from Startup to Public Transition

34’39: Navigating the Terrain: The Dynamics of Private Fund Administration in Changing Economic Climates

38’56: Charting the Future: Carta's Vision for Empowering Founders, Revolutionizing Fund Administration, and Expanding Global Footprints

40’57: The channels used to connect with Anthony & learn more about Carta

Illustrated Transcript

Lex Sokolin:

Hi, everybody, and welcome to the podcast. I'm really excited about today's conversation with Anthony Cimino, who is the head of policy at Carta and has a fascinating background in government and policy around the financial services industry. We'll talk about Carta and the private markets industry as well as how to build in the space. Anthony, welcome to the conversation.

Anthony Cimino:

Thanks so much for having me. Really excited to be here.

Lex Sokolin:

You have a background that we don't often encounter on these fintech conversations, and so I am really excited to learn more about it. How did you get involved in finance and policy? What was that overlap like and what led you into it?

Anthony Cimino:

Well, hopefully my background will become more relevant and more prevalent in the industry as policy and regulation do play a bigger role in it. But to your point, I come from the public policy world, and I started on Capitol Hill working for the Committee on Financial Services, basically right as the financial crisis happened. So worked with the Committee of Jurisdiction on how to respond to that. And then as the crisis was addressed and we looked towards what the regulatory regime should look like going forward, worked on things like Dodd-Frank, and then moved into public policy working for large financial institutions and specifically trade associations that represented asset managers like BlackRock, insurers like MetLife, and banks like JPMorgan Chase, running government affairs for the Financial Services Roundtable and its successor organization, the Bank Policy Institute. And so, my background is in a largely regulated policy space and came to Carta as they were thinking through not only some of their areas that they had to start dealing with regulations and getting approvals on, but as the space itself started getting more regulatory constraints put around it, which I know we'll talk about shortly.

Lex Sokolin:

Before getting there, I'd love to just learn a little bit more about the meat and potatoes of what it means to work on bank policy, and I'm sure there's a distinction between what the regulators do and what happens in the legislature. Can you walk us through in those early years of yours, what does it actually mean to work on policy and how does the machine function?

Anthony Cimino:

Yeah, so to your point, there's a lot of different areas of government. There's the agency side, which is if you think about the Federal Reserve, the SEC, Treasury and others that are really focused on rule makings, enforcements and the mechanics, and then there's the legislative side, the law-making side. And I came up through the congressional ranks and it was a fairly unique time where six or so months after I started, we saw the first parts of the financial crisis where at that stage everyone thought it was largely contained to the mortgage market. It then obviously spilled out into the broader economy as the cycle of defaults led to economic contraction, job loss, which then further led to defaults, and then it just kind of spun out into more and more toxic assets and how banks had to address them. And so well, what does that really mean?

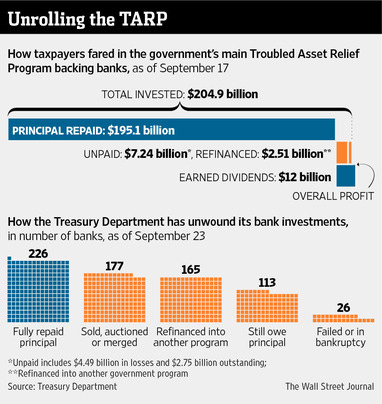

Well, in many cases on the congressional side, it was not only identifying what was going wrong but how Congress could work with the regulators to address it. And the most obvious manifestation of it is how do you solve that problem of banks holding a large amount of toxic assets, which not only jeopardized their balance sheet, but constrained access to credit and ultimately created more economic problems for the wider economy, and what are those solutions? And so, the most obvious solution that ended up coming out of it was we needed to inject capital into the banks, and that was the TARP legislation that seems so antiquated and old now, but was Congress passing $700 billion to basically capitalize the banks.

And we came to that solution after a number of different ideas, and I give the agencies a lot of credit and how they thought through these things. There were a lot of smart people working on it. And then Congress had to assess what those solutions look like and what amount of money they could provide. And so really identifying the nuance as well as how to address some of the frictions we saw there on that front. And so that was a lot of the crisis.

The aftermath is then, well, how do we stop this from happening again? And there's never a perfect solution. And oftentimes you see in the policy world some of the broader base solutions potentially overcorrect or have unintended consequences. And I think we saw some of that with Dodd-Frank, but then that was a two-year saga of how do you put in place a regulatory regime that does more to ensure the safety and soundness of the banking system as more people realized it's not only key for households and consumers, but it's so interconnected to the economy writ large that failures represent a systemic risk. And so how do you guard against that both at a systemic level but at an institutional level and ultimately ensure that people are going to continue to have access to credit and continue to have the lifeblood of the economy going forward.

Lex Sokolin:

I think we're in a pretty dire cultural moment as it relates to trust in institutions broadly, whether those are financial institutions or whether it's the democratic institutions. There's so little trust in getting these large-scale things right and building systems that benefit people. What is the democratic process or what is the process by which the machinery takes the interests of the people and translates them into policy, which I guess means bills or regulation. What's that connective tissue between the issues that regular people have and then the things that become law?

Anthony Cimino:

It's a really good question, and it's something that I think we as a society are struggling with, to your point, that the lack of faith and the erosion of credibility in institutions. And I think the question you're asking is actually getting at, in many cases, a solution, and that's why engagement matters. I think there seems to be a very big disconnect that's feeding into a lack of trust and credibility among a lot of segments of the population on both sides of the aisle into why institutions are behaving the way they are, how they're making decisions and what those outcomes are. And I think how we try and solve that is really thinking through paying attention and engaging.

And so, I think to your question, well, what does that engagement look like, how does it manifest and what outcomes does it lead to? One, I do want to be clear, it's not overnight. These are long-term engagements and education opportunities, but this is why, for instance, Carta has a policy team and we talk to folks about policymakers want to hear not just from Carta's policy team, but the companies we represent and serve that are on our cap table, the funds that we work with and provide fund administration services, because policymakers do want to understand what that day-to-day impact is going to be as well as the longer-term impact on their decision-making. And in many cases, the ideas for policy come up because of ideas brought to them by stakeholders.

And so, to put a finer point on this, when we're talking through how funds should be regulated, they can hear from stakeholders in the policy environment, but hearing from the operators is going to really help them understand the implications of an SEC rule or why accredited investor and expanding that's going to be important. And talk to your local congressmen, engage with them, write comment letters to the SEC, work with companies like Carta that do have a policy footprint, and our goal is to translate what your experience is into policy solutions.

And that's not going to happen overnight, as I mentioned. It takes a while to turn a bill into a law. It takes a while for regulations to come forward. But in many cases, it seems so disconnected that it feeds that further erosion and public trust of these institutions where I think engagement won't be a panacea, but in many cases it can close some of that connection down, give more insights into both sides of this, both the stakeholder side as well as the policymaker side, and ultimately lead to better outcomes. I do always try and start from the place that even if I disagree with the decision a policymaker makes, he or she is trying to do their best job on it. And they might have a different solution that they're indexing for or problem they're solving for, and as a result, they're coming from a different perspective. But I think they're trying to do the right thing. And to help them do the right thing, I think it's important that stakeholders, people, institutions engage because policy is going to be shaped by those who show up.

Lex Sokolin:

That's really interesting. Policy is going to be shaped by those who show up. Just one last question on this topic. Because I think it's so relevant across markets, whether you are, like Carta, engaged in the private markets and want to create access for people, to loosely speaking private equity, or whether you are a banking-as-a-service provider and the FDIC is chasing around the bank in which you're opening accounts, or whether you are a crypto company and are unable to bank or offer products because of the ambiguities in the market. Not showing up means you're by default losing your hand.

I do want to just ask another question here, which is you said it's the stakeholders that shape the process. Given you have pretty deep experience in this machinery, what are the clumps of influence that do shape end of the day, either the regulation or the legislation? It feels like the comment letter is not enough. It might be a tilt of 1%, one direction or the other and that there's many more waves underneath that are kind of mysterious and unclear, but what are the forces that leads to an outcome, especially as it relates to financial markets?

Anthony Cimino:

It's a really good question, and I think there's been an evolution on who is really shaping this, but as a step back, this is why Carta's invested in a policy team. As I mentioned earlier, I came from the very regulated bank space and they are filled with policy experts that engage regularly for banks, large asset managers, and for lack of a better word, the bigger institutions that are incumbents across different sectors. And whether they're regulated or fighting off regulations, in many cases they see that as a competitive advantage and in some cases a moat competitively. Carta invested in a policy team not necessarily for Carta's own business, but how we think about serving as the connective tissue between this ecosystem, this innovation ecosystem, the startups, the funds, and the employee owners of these companies and the policymaking community because it didn't really have a voice. And to be fair, as private markets grow and we unlock more capital and lower barriers to entry, that accrues to the benefit of Carta.

So, when I say it's not just for Carta as a company, it's for the ecosystem, it still benefits Carta, but what we wanted to do is make sure that this ecosystem had a voice at these tables. Because I think, to your point, it is great and we really encourage and do actually a lot of events with our customers and stakeholders across the country and try and connect them in with policymakers, and we try and bring their expertise and their experience and translate that into comment letters or direct policymaker engagements, or when earlier this year, Carta's CEO testified before Congress to make the case on this. These voices are important, but it needs to be sustained.

And I don't think it's fair for me to ask everybody while they're building a company, which is a 24/7 job, we're launching a fund which is a 24/7 job, to say, "Hey, you need to do policy every day with us." That's not your job, but we need to learn from you and ideally engage you at the right times to pull your thread forward and engage with policymakers. But then it's incumbent on us and others similarly situated to continue to make those cases because the one-off engagements are important. But what we need to do is build a cadence around that, and we're seeing that not only with the comment letter submissions, we're seeing that with legislative meetings, we're seeing that with the hearings and submitting and testifying.

But we're also seeing that when people are continuing to show up at these town halls and really keep that cadence coming up there because without that happening, it will fall to the larger institutions who can invest their scale into policy development that not necessarily control it, this is not one of those conspiracy theories, but are the ones really doing a lot to inform and provide the resources to policymakers. I think the innovation community is so key and has an important story to tell as to what it does not only for today but the future of American innovation and competitiveness, that its voice has to be heard. And we're seeing that debate happen on things like accredited investor, on things like qualified small business stock, on things like research and development tax. And if we're not at that table, somebody else is going to shape it.

Lex Sokolin:

Yeah, I mean, I found surprising that when you do bring these issues into politics, sometimes they're represented by parts of the process or a party that you might not have aligned with before, but these issues do find a home and once they do find a home, they do get kind of negotiated into some sort of forward progress. Let's switch tracks to Carta, and for folks who might know the name but not be familiar with the scale of the company and the traction, could you give us an overview of what are the main business lines and then what's the size of the business in terms of whether it's customers or equity on the platform or any other metrics that you can think of.

Anthony Cimino:

For those that are unfamiliar, Carta is a company that helps growth stage companies and their investors issue equity, value equity, and manage equity. And what does that mean? Well, our core business is cap table management, and as many folks are probably aware, in public markets it was more readily available that record of ownership, but in private markets there was no single source of truth. In many cases it was built on paper certificates with different records. And so, 10 or so years ago, Carta digitized that and created its capitalization table business, and today it's grown into 40,000 companies on our platform for whom we oversee and support on their cap tables. And if you're going to issue equity, you've got to be able to value that equity. And so, Carta quickly provided valuation services for those companies and we're a very large valuation services provider. We turned that lens and provided many of those same services or similar services to the investors into these companies. And so today we've got a growing fund administration business, and we support around 7,000 fund vehicles on that.

Now, those two core businesses provide us great line of sight into private markets writ large. And so, we have built out additional ideas on things like how do we think about companies and compensation? And so, we've launched things like Carta Total Comp, which as we're seeing policymakers ask for increased transparency into compensation levels, Carta can help companies identify what they should be paying your first engineer or your third marketing person and what these bands look like based on market. And so, we're able to pull those core businesses and the value we've got there into different vectors that can provide additional support for a lot of these companies and funds, just as an example there.

Lex Sokolin:

What has the effect been on the private markets as a result? I mean, going from a sea of disconnected paper to a more digital infrastructure, do you see things happening at the market level in terms of behaviors of different companies or funds?

Anthony Cimino:

Well, I think that the first implication of what Carta was able to do is we made it easier and less costly to issue equity and to help, especially not only founders, but the employees that they would hire and issue equity to, get that equity, understand its value and optimize its value. And that sounds fairly obvious today, but 10 years ago that was not necessarily the case. And even today there are still aspects of how do we think about educating employee owners so they can optimize their equity. But that I think is the first implication of it took a very manual process that not only was costly, but created a decent amount of confusion and hurdles to it and really made it easier to issue equity and create more owners as a result of it.

I think the second implication is how we think about connecting more information in an opaque private market piece. And so not only do companies have, of course, greater understanding of their cap tables, but the investors now have that. And when we're thinking through and seeing rounds raised, time between rounds, how employees are compensated, equity pools, Carta's got a number of those data points, and on an anonymized basis, we can put that out to the market to further inform how whether founders or employees should be acting or investors should be acting based on what they're seeing elsewhere in the market. And so, I think that's allowed for a greater and informed decision-making aspect across all those nodes.

And I think what we'll see probably on an extension of that, but especially because of the policy lens, is there a drive towards not complete standardization, but are we seeing more standardization come into private markets than we would've seen five years ago? I do not think that there will be a world in which it operates similarly to public markets. I think that's obviously a spectrum of how we think about capital markets from those early stages to those more mature public market stages. But we're seeing, I think, this information and greater technological influence create more opportunities for standardization that can continue to lower barriers to entry for founders and for funds.

Lex Sokolin:

So, maybe even going to a simpler question, why are private markets so hard? If I want some Apple stock, I just open up Fidelity brokerage account and yada, yada, yada, KYC. But once I'm done with that, I can just buy an Apple stock. And if I want to buy Bitcoin, it's even easier. I can just fund an account and off I go. Whereas with private markets, it's just this nightmare of paper and exceptions to this rule and to that rule and safe harbors everywhere and it seems to be designed through sort of death by a thousand cuts rather than making it easy for people to participate. Why is that? What is the core difference between the public and the private markets?

Anthony Cimino:

You hit it on the head, and this is what we spend a lot of time thinking through. And again, we're not trying to make private markets public markets, but we do think that there is an opportunity to modernize the regulatory regime to make them more accessible and easier to navigate for both investors and the builders in private markets. And so, I think to pull some of the threads you pointed out is, one, these are privately held companies. And so, from an investor access perspective, regulators have said these companies do not put out the same level of information as publicly registered companies. And as a result, we want to limit the investors that are able to invest in them. And how they've done that is through things like the accredited investor regime, which determines largely through thresholds around assets and income who can invest in private companies. And so, if you don't pass that threshold, you're not even eligible in many cases to hold equity in these companies.

Lex Sokolin:

Why do I need to be eligible to make decisions about my money? That in itself as a principle is, to put it mildly, paternalistic and offensive.

Anthony Cimino:

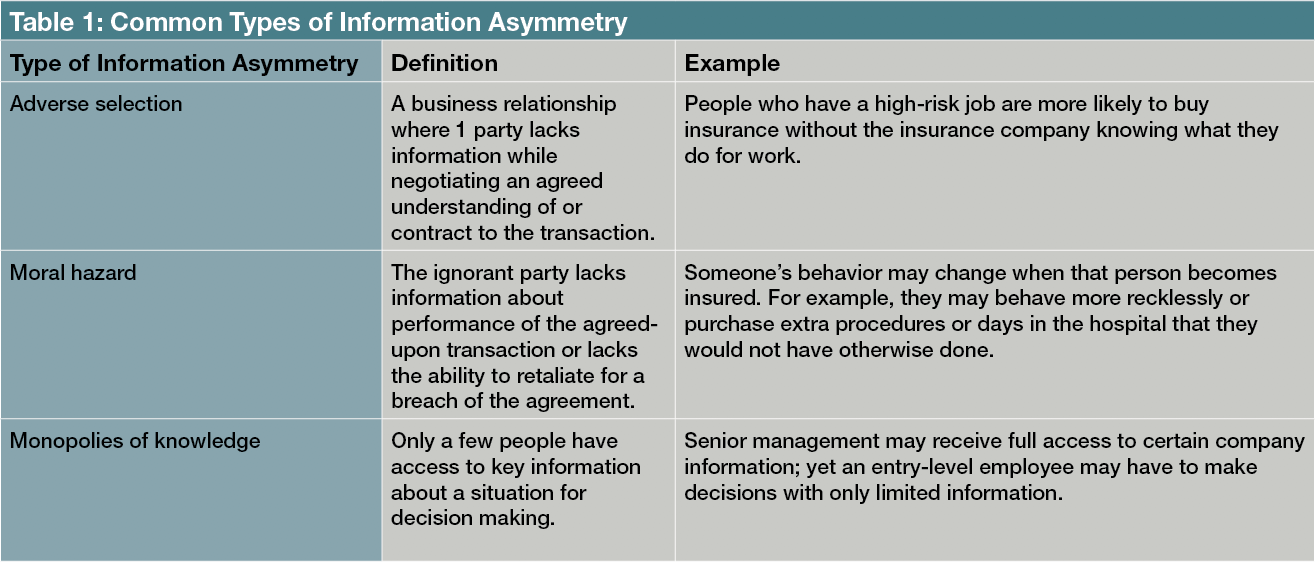

And this is, back to my earlier point of there are major philosophical differences that lead to these outcomes, and no matter what side you're on, these are the debates we have to have. The reason why these restrictions were put in place is from an investor protection perspective, and to your point, that's very paternalistic, but what they see in private markets are companies that don't put out the same level of information. So, there's opacity around information to the extent that there is information, many of the skeptics would argue it's asymmetrical, where larger investors might have access to information around those companies or the broader market sizing, smaller investors might not. So there seems to be an uneven playing field.

And then thirdly, there's a lack of liquidity in the space. And so, folks need to understand those risks. I think someone, based on your question, like you or in my case, me, would say is like, "Well, that's my job to understand those risks. It's still my money. I should be able to invest it where I want." But from the other side of the coin, they'll index for investor protection and say, "Given these elevated risks, we want to restrict who can invest in these companies. And we don't necessarily know how to make sophistication judgments. So, what we'll do is we'll put financial thresholds in place which don't speak to sophistication, but can in some cases speak to financial resiliency." So, this is just a philosophical divide. We spend a lot of time on this because while many people are locked out of private markets, that's where we're seeing so much economic value generated and they're missing out on that economic value, and that's why we are trying to increase on-ramps to accredited investor. To your point though, that's a philosophical divide that is in some cases can be seen as very paternalistic.

Lex Sokolin:

It is a rhetorical question and you hit the nail on the head. The other adjacent point is that wealth creation is largely happening in the private markets and it's taking companies far longer to go public, and by the time they go public, all of the early growth and expansion that would in the past have been captured if a company went public at 50 million and was available to retail investors, all that growth is gone by the time they IPO at 10 billion or more. And so, participation in the private markets is really one of the main levers for people to have access to economic growth and innovation. And because of the dynamics of when companies go public and how large many venture investors have gotten in terms of their fund size, you actually completely miss out on those early years. Now consumers are more protected because they're limited to their 60/40 portfolio and five to 10% returns, but they can't avail themselves to the risk that prior generations have benefited from.

Anthony Cimino:

100%. And it's something that we're actively working with policymakers on to expand those on-ramps. And one, I think that there are opportunities for on-ramps around sophistications and certifications and educational or sector backgrounds, but those are going to take a long time to convince lawmakers in this more partisan environment around private markets that they're important. And furthermore, I also think there's opportunities for structured access of, in many cases, you should be able to use professionally managed funds to invest in private markets, even if you're a retail investor that might not be deemed accredited. And there's examples of, well, if liquidity is an issue and duration risk is the factor that you're trying to solve for, how do you think about using retirement account investments for private markets, and/or how do you think about giving more retail investors access to fund managers?

And so, I think that there's an opportunity here for structured access. Ideally, we can do both, but there are a lot of on-ramps we need to explore because you're right, much of the alpha is being captured in private markets. Companies that do go public do so later in their life cycle, and so people are missing out on that growth, and that's only going to exacerbate income inequality, much less restrict the amount of capital for companies beyond major tech hubs.

Lex Sokolin:

And this isn't some grand conspiracy. It's, I think, kind of a systemic trend. You have wealth concentration simply by the nature of money cumulatively flowing into capital compounding over time. If you just leave capital in place, by the end of it, you're going to have more inequality than not. And that's not malicious in any sense. It's sort of just almost the fact of capitalism, but you do get this blowback as a result.

Anthony Cimino:

What I would just add to that, to your point, it's almost a decision in and of itself not to make a decision because it's already in that compounding cycle in those areas. And the SEC put out a report, I want to say it was a year ago, that the typical distance between the lead investor and a series seed or series A company is a hundred miles. And although capital's mobile, proximity still matters.

And when we think about broadening not only access to investment outcomes for more Americans and people, but also how we think about providing capital beyond places like SF and New York to startups and emerging fund managers to really broaden the innovation economy, that hundred-mile proximity is going to matter. And so, it is very much of how do we think about lowering these barriers to entry on accredited investor, which is a national standard, mind you. So, $200,000 in San Francisco versus Atlanta makes a big difference in income. But how do we think about addressing things like accredited investor to build capital pools in places like Atlanta and places like Detroit and places like Ohio, so we're not just having this compounding effect you just referenced just continue on in perpetuity without expanding it into more areas.

Lex Sokolin:

Got it. Okay. So switching back to Carta and the platform, in my mind, the default product is onboarding the cap tables of companies into a digital format and then facilitating the tracking of cap tables over time in the fundraising process and so on so that you're not living in a spreadsheet, but you're living in a platform where you can bring people on and off and make it much easier for investors to know what it is that they have without reading through hundreds of pages of legal documents. So, once you have this large data infrastructure, we've talked about onboarding more people into owning financial instruments from the private markets, what are the opportunities for Carta as it relates to that big data set? Is the terminal destination to have all this data and make it accessible to people, or there are other adjacent things that I know the company has tried, from considering bolting on secondary markets to working more deeply with investors, and there's different places where you can integrate functionality. So how do you think about the sequence of the parts of Carta that are being built?

Anthony Cimino:

I think for us, the end game is not, to your point, the terminal goal is data. To us, the end game is not data. The end game is how do we support founders building and pulling their cap tables onto the platform, making it easier for them when they're fundraising or issuing equity folks. And then being able to provide them the valuation services. And then being able to inform their investors with those same sets of information pieces. I think, to your point, how do we then use that data to inform the ecosystem? As I mentioned earlier, we put a lot of that out and, again, in an anonymized form to make sure that folks have as much insight as we can provide into the data. But then there are other areas, as I mentioned earlier, like Carta Total Comp where we can help people navigate how they're thinking about the hiring and attracting and retaining the best talent.

We could see this also come up in areas around new requirements and standards being put in place by the SEC, for instance, on the fund administration side, where under a recent rulemaking, they are now going to require quarterly statements that will report on performance fees and expenses between GPs and LPs of not only can Carta build out those types of templates, but we have the underlying data that can inform a lot of that, whether it's coming from the LPA or the performance of the funds. And make that easier for those GPs to give that to their LPs, not only to ensure the LPs have line of sight into what they need, but that these types of funds and advisors are compliant with SEC regulations. And I think when we're thinking about the fund administration business, it's not just the funds we currently have, but how do we think about that as it's growing into more funds and increasingly not just in the venture space, but in places like private equity and dealing even with more asset classes.

Lex Sokolin:

Let me just ask the question, which is, I think you've exited the secondary markets business, is that right?

Anthony Cimino:

Yes. Earlier this year our CEO announced that we would be shutting down the secondary market business for Carta, specifically the block trading aspect of it.

Lex Sokolin:

You have to explore services that compound value for your existing customers. So, when you think about the stakeholders involved that you're serving, is it primarily, is it the investor, is it the CEO, is it the CFO? What's the persona? When I think about the secondary markets business, in my mind it becomes the customer is whoever wants the transactions. So, a brokerage is really different from a custodian and the custodian is different from a settlement depository or something like that. And each of those is kind of optimized against the different customer persona. And then you can't win unless you're obsessed about the customer that you know. So, when you think about the business lines that you have today, who is the core target in terms of being sold to?

Anthony Cimino:

Yeah, and I think this goes to the decision around shutting down the secondary markets business. And Henry wrote about this I think eloquently in his announcement to do so, but this is a company that was really built to support founders and that continues to be the focus of today. And then to your point, it's how do we think about supporting founders as they're building and what aspects we can add onto that. An important part of that is making sure that they're able to communicate and work with their investors effectively. And so that's why we built out the fund administration aspect of it and worked to solve a lot of their problems. So, in some cases that persona or that customer segment has also expanded to include those GPs or those fund CFOs, but that's all in an effort to how do we think about connecting value across this ecosystem on that front.

Lex Sokolin:

I'm sure that a bunch of companies on your platform have gone public. What's that like? What's their experience like, and is there a path recorded to expand into that market?

Anthony Cimino:

Yeah, so this is something that we've always focused on is how do we support you from that idea when you're first incorporating to the day you go public. And in the past, we've actually dabbled and worked on public market solutions on that front. We don't do that today, but we work very hard to make sure that we can support a customer not only through that idea, but all the way through that enterprise motion into that transition where they would be then moving to a different provider in public markets. And so, it's definitely a product that we, again, we're very proud of. It's our core product. But cap table is something that we are confident can support all the way through enterprise, all the way to the day you go public.

What I've always loved about Carta is how we think about capital markets as a spectrum where we want this to be, especially on a policy side, an incremental growth into that curve, not a step curve. And on the policy side, it still remains a step curve to transition from private to public, but what Carta does is try and smooth out as much of that as possible on the cap table and equity management side to ensure that when that handoff is made, not only is that company taken care of and prepared, but the ownership group, whether those are the investors or the employee owners, have all the resources and tools and a clear path forward to optimize their economic value.

Lex Sokolin:

Okay, that makes sense. If we click on the fund administration problem, before we've talked about the difference between private equity and how people access that versus public equity. Can you talk about the difference between what a mutual fund or an ETF needs to do versus what a manager of a private fund needs to do? Another framing of that is what is a private fund.

Anthony Cimino:

We think about these obviously as closed-end funds where a fund manager is raising capital, GP or investment advisor's raising capital, that capital will be in the fund or at least committed to the fund for a certain duration of time. There is a limited partnership agreement that outlines those parameters. And then the operations and execution of that are built on that limited partnership as well as the side letters, but it would be a closed-end fund and in many cases would be built to allocate towards whether it's a venture-backed company or different types of private equity strategies around that. And that can be very different than some of the funds on the public side where folks can come in and out of them. And so that's why it's a little bit of a different motion here because it's long-term lock-up and in many cases what we're trying to think through is how we administer this to make it easier for fund managers to just focus on their business.

And so, thinking through how do you maintain and update your schedule of investments, how do you think about the value of those investments, the performance of those investments, the waterfall implications for your LPs, and being able to report that smoothly and on the terms that you've agreed to and that works not only for you but for your LPs on that front. And so, it's a business we've built for some time, and we see this as a real opportunity not only for Carta but for the market to continue to evolve, as we've discussed, into ways that can expand access because there are now greater opportunities for not only unlocking more investor capital into these areas, but creating more information flows and reporting around it.

Lex Sokolin:

What has the trend been for private fund formation, and maybe performance, but more in terms of what Carta experiences over the last couple of years? We've had a pretty drastic macro regime change from zero interest rates to 5% interest rates after all the COVID supply chain stuff. And there was of course the contraction in '22. So, I'm curious what kind of trends you're seeing from the fund side across the platform.

Anthony Cimino:

We saw, I think, to your point, a large amount of funds launch. So not only do we see the upmarket and more established funds continue to raise and deploy, but for the past few years we saw a large amount of first-time fund managers and emerging managers come out of the gates, raise and start deploying. We've seen that start to retreat a little bit, and that's a big concern for me and the policy world as well, because as I mentioned, we see the emerging and first-time fund managers as a key channel through which we can broaden venture and innovation, identify new entrepreneurs in different regions, and ultimately provide the capital to drive that.

And so, as we're seeing fewer managers not only launch, but in many cases those first-time fund managers not pursue a second fund or not be able to raise a second fund, what is that going to mean for the macro trends here? And that's why we think that there are ways on the policy side to lower barriers to entry on that, and that's why we spend a lot of resources. But I think to your underlying point, whether it's because of the interest rate environment, some of the economic contractions that have happened since, and as a result we've seen some of the LP capital move back to those more traditional established sources, that trend towards emerging managers has come down from what might've been a high watermark the last couple of years. And our goal is to figure out not only how we support the upmarket and established, but how do we think about pushing the emerging manager curve back up and then of course supporting them as they grow.

Lex Sokolin:

That's certainly consistent. It's easier to buy treasuries than to figure out which emerging manager is not going to lose your money. As we wrap up the conversation, I'd love to learn kind of what are the things on the horizon for Carta, both from a market perspective and a growth perspective. Are there things that you're excited about that are going to happen in the future? And as you're looking towards the development of the private market sector, what are the things that you're focused on and are excited about?

Anthony Cimino:

Yeah, I think, one, we continue to be excited about helping founders build, and that's our core cap table business, and really making sure that we're lowering barriers and providing them the resources to continue to raise capital, grow their companies, and provide more innovation. I think to the fund administration business, we're seeing a lot of signals as that's transitioning because of a policy shift, because of industry expectations and because of technological innovations, the capacities there. And that's, again, supporting not just the venture aspects, but increasingly private equity. And so, I think that's the other big thing that's really exciting as we're seeing. Three, and I think you've probably seen some of this in the news, Carta's increasing its footprint into more markets globally and identifying ways that we can learn about those markets and support them. Each of them has their nuances and we have a job to do when it comes to entering them as to how we position ourselves in the right ways to support those ecosystems.

And I think underpinning all of those, and this is self-interested, but there is that shift in the policy world that I think is bringing about in some cases, challenges but in other cases, opportunities, where Carta really takes policy very seriously and not in a, how do we beat it back, but how do we channel it in an effective way that if policy is infrastructure, which is my underlying thesis, how do we use that infrastructure to unlock capital, how do we use that to create appropriate access and standardization that ultimately gives folks more line of sight to make better decisions and ultimately engage in private markets, whether they're the asset classes in venture, private equity, real estate, other liquid assets, or other private assets in meaningful ways, and really channelling policy to not bind that, but unlock that. But I think those are the three vectors that particularly excite me, and I think policy underlines all of them.

Lex Sokolin:

Anthony, if our audience wants to learn more about you or about Carta, where should they go?

Anthony Cimino:

Would love to engage with anybody who's interested in these types of issues. Please visit us. There's a Carta Policy Desk that can be accessed. Go to carta.com. And then we put out a weekly newsletter that we can sign up for there. But a huge amount of resources. If you're building a fund, we just put out that regulatory playbook. If you're launching a company, we've got Corporate Transparency Act and tax advice on stuff like that. So, a huge amount of resources on the Carta Policy Desk.

Lex Sokolin:

Fantastic. Thank you so much for joining me today.

Anthony Cimino:

Really appreciate it.

Shape Your Future

Wondering what’s shaping the future of Fintech and DeFi?

At the Fintech Blueprint, we go down the rabbit hole in the DeFi and Fintech world to help you make better investment decisions, innovate and compete in the industry.

Sign up to the Premium Fintech Blueprint newsletter and get access to:

Blueprint Short Takes, with weekly coverage of the latest Fintech and DeFi news via expert curation and in-depth analysis

Web3 Short Takes, with weekly analysis of developments in the crypto space, including digital assets, DAOs, NFTs, and institutional adoption

Full Library of Long Takes on Fintech and Web3 topics with a deep, comprehensive, and insightful analysis without shilling or marketing narratives

Digital Wealth, a weekly aggregation of digital investing, asset management, and wealthtech news

Access to Podcasts, with industry insiders along with annotated transcripts

Full Access to the Fintech Blueprint Archive, covering consumer fintech, institutional fintech, crypto/blockchain, artificial intelligence, and AR/VR

Read our Disclaimer here — this newsletter does not provide investment advice and represents solely the views and opinions of FINTECH BLUEPRINT LTD.

Want to discuss? Stop by our Discord and reach out here with questions

Share this post