Hi Fintech Architects,

Lex interviews Shachar Bialick, the founder and CEO of Curve, a fintech mobile wallet.

Notable discussion points:

Bialick's background as a serial entrepreneur and his experience in the Israeli military shaped his ability to solve problems and work in high-stress environments, which are key traits for a successful founder.

The initial idea behind Curve was to create a "wallet to rule them all" - a single interface that could consolidate and manage multiple payment cards and accounts, providing more value and convenience to customers.

Building Curve involved navigating complex challenges, such as convincing payment networks like Mastercard and Visa to change their rules to allow Curve's back-to-back wallet technology. This required a resilient, innovative, and persistence approach.

Bialick emphasizes the importance of building a company culture that fosters curiosity, adaptability, and a belief that "everything is possible" rather than focusing on perceived limitations.

Lastly, Bialick discusses the evolution of the fintech landscape, including the challenges faced by neobanks in creating true financial marketplaces, and the ongoing issues with the implementation of open banking standards.

For those that want to subscribe to the podcast in your app of choice, you can now find us at Apple, Spotify, or on RSS.

Background

Shachar began his entrepreneurial journey at 21, founding his first startup and achieving four successful exits across different ventures. Shachar has also previously worked as the head of product at Checkout.com, as well as the CEO of Machshavot SmartJOB and SmartEQ. Shachar has also taken on roles such as a junior associate at Gornitzky & Co., a team lead at the Israel Defense Force, and a TA for Dr. Nimrod Kozlovsky.

Shachar is known for his innovative approach to disrupting traditional industries, particularly in fintech.

Shachar Bialick has a Master of Business Administration (MBA) from INSEAD, a B.A. in Economics from Tel Aviv University, an LL.B. in Law from Tel Aviv University, and a BSc. in Computer Science from Bar-Ilan University.

👑Related coverage👑

Topics: Curve, ApplePay, Google Wallet, PayPal, Tink, neobank, fintech, wallets, payments, paytech, NFC, Open Banking

Timestamps

1’02: From Military Service to Fintech Success: Shachar Bialick on Founding Curve and Redefining Payments

9’10: The Resilient Founder: Risk-Taking, Leadership, and the Cultural Mindset Behind Entrepreneurship

14’59: From Unbundling to Rebundling: Building Curve to Solve Financial Fragmentation

20’50: Revolutionizing Payments: Curve's Ambition to Unite Financial Ecosystems

24’26: Trailblazing Curve: Overcoming Challenges to Redefine Payments and Build a Global Fintech Ecosystem

30’23: Project Elah: How Curve Challenged Apple’s NFC Restrictions to Redefine Digital Wallets

34’50: Shaving the Lion: How Curve Built a Culture to Overcome Industry Challenges and Innovate

39’05: Challenging Apple Pay: Curve’s Strategy to Deliver Tangible Customer Benefits

42’01: The Evolution of Fintech Infrastructure: Challenges, Opportunities, and the Role of Open Banking

51’54: The channels used to connect with Shachar & learn more about Curve

Illustrated Transcript

Lex Sokolin:

Hi everybody and welcome to today's conversation. I'm super excited to have with us Shachar Bialick, who is the founder and CEO of Curve. Curve is one of the original fintech mobile wallets and I'm really excited to explore their story, as well as the broader wallet ecosystem. With that, Shachar, welcome to the conversation.

Shachar Bialick:

Hi Lex. I'm excited to be here. Avid reader and listener to your recent podcasts. I look forward to share some of our point of view on the market with the listeners.

Lex Sokolin:

Fantastic. I'm humbled. I want to get to Curve because it's such an interesting story. Let's just set the scene about you for a little bit. A lot of your background is entrepreneurship, is fintech, is taking risk. Can you talk about what got you to move in this direction, what got you the capacity to be a founder, and maybe some of your earlier experiences.

Shachar Bialick:

Sure. My background is I was born and bred in Israel. In Israel you also have compulsory service in the military, and I always thought of it as a remarkable experience, for many aspects. First, it creates a beautiful melting pot between the different classes and people in Israel. But more than that, it also allows you to have a similar way of communication, and it also trains you, or gives you certain traits and skills that, in many, many times and aspects, are relevant for the civilian life, for commercial, for your career.

For me, it already starts I think in the military where I was assigned to Special Forces, where the training is almost two and a half years, and they kind of break you apart and rebuild you again in terms of the way you think, about the world, about yourself, about your capabilities, and also how to operate in large teams, in stressful scenarios. Basically, all the things that founders need to have in terms of the ability to solve problems and work in teams and operate in highly stressful scenarios. With that, during my military service, I got injured with two members of my team. And when we went to civilian life, our first startup was taking the technology we used in the military and commercialize that.

And that startup was really about... I don't know if you're young enough to remember, but back then when you had Nokia phones, they didn't really have IMAP and POP3 protocols like we have today, and the way to connect to the internet did not really exist. So, we commercialized technology that referred today in the market as WAP protocol, that allowed you to communicate between old legacy phones, feature phones, to the internet. This is how, back at the time, we customers got messages with images inside, or MMS as they were called. That's a good example of how WAP protocol works.

That was just something we were interested. We didn't really know what we were doing. Just a good team, smart people, and technology we thought relevant in the market. And we sold it within six months, not for a large amount but it was a very nice success, and we got the entrepreneurship bug. Later on, we as a team followed up and created the second, the third, the fourth startup. Each one of them were in very different industries. The second one was eCommerce, the third one was medical cannabis, where we had to regulate it in the market. The fourth one was an African trucking system.

So all very different industries, but the pattern or the thread across them was how a great team that thinks differently about a problem that we found in the market can solve that problem through technology or innovation of business models and operations. After my fourth company... if you think about my career back then, it was 12 years of very, very high intensive work, from military at the age of 18 to my last company at the age of 30. And during this time of building startups, one of the things you always get problems with, or a lot of cost assigned with that is payments. So as a founder, you have to learn a bit about finance work, how the financial system work, and you start seeing all the different problems that exist.

In fact, if you look back to 2006, the idea of Curve has already emerged in my mind. Back then the interface was web interface. We didn't have smartphones in 2006. But I thought to myself that either Facebook or PayPal would find a solution, and eventually we'd decide not to do anything that we did. But lost visions like lost loves are the most romantic ones. So, after my fourth company, I knew what I wanted to do is start up a new payment space. There were a lot of opportunities I saw there, but I needed to have a year off after 12 years of hard work.

We're Jewish. My mom was like, "What do you mean, a year off? Go study." So, I went to the best business school I could be accepted to with the least amount of work required, which was INSEAD in Singapore.

Lex Sokolin:

I hope there are no listeners that went to that business school.

Shachar Bialick:

It's a great business school. Don't get me wrong. It's just hard to get in. But unlike many I think other MBA students that went there to change their careers or to learn a new subject, I went there more because I wanted to leave my bubble in Israel and see what is outside of Israel and different talents and cultures and experiences and also travel a lot. Singapore has a very unique type of people. Very smart, very critical, very successful, but they all want to celebrate life, and enjoy life. And we can maybe open a bit for me at INSEAD and my experience there... when I went to see INSEAD, I've already had four exits behind me. I'm fine financially. I'm pretty successful in Israel, very knowledgeable and known in the country. And I was very arrogant.

When I got there, within two weeks, I had been slapped left, right and centre. The people there were smarter than me, more accomplished than me, more traveled than me. Basically, the bar that surrounded me was much higher. And I remember myself, two weeks in, saying, "Wow, so that's the bar. That's what great looks like." And that's one of the remarkable experiences of INSEAD, where if you think you were successful before you get there, now that you got there, there was so much successful people there, that your bar of what great looks like increases pretty swiftly, and you learn a lot from these people.

So it was one of the best experiences I've had in my life, but one of the things I realized during my studies there is that I've never been an employee in my life. I never really got feedback, direct feedback in my life, because I was always the founder or the CEO and never you really get feedback properly as a founder or CEO. And at the same breath, I also wanted to do more about payments, wanted to learn more about payments. And those two things that I want to work for someone and see what it is to be on the other side, how leadership and culture impacts employees, to get feedback as an employee, and at the same time learn payments much better.

I decided after INSEAD to move to London and join, back then, a very small company called Checkout.com, which is a merchant acquirer. There, I worked with the founder, Guillaume, and built a whole new gateway with him. The same gateway technology we had been using with them until I think a year ago, that now launched a whole new technology, and learn the ropes of payments much better, but also learn that I'm probably the worst employee out there. I'm much better as a founder. And after delivering what I committed to Guillaume, the alpha version of the gateway, which was almost 11 months after I joined Checkout, I decided to leave and move back to my own doing of being a founder.

And that kind of bring us to the beginning of Curve, which was launched, or the company was formed about a year afterwards.

Lex Sokolin:

There is so much in there that I'm interested in, but maybe we can go really abstract. You mentioned a concept of, you're not an employee, you're a founder. I'm interested in that. I'm also interested in this idea of leadership. Not everybody can go out there and say, "I've just gone through this experience that's been really difficult, and what I'm going to do as my next thing is again start from zero and have that most difficult experience again." So, what do you think it takes to want to do that risk-taking? What is it that you need to have to be willing to grab that creative spark? And how does leadership tie into it?

Shachar Bialick:

Number one, being a founder or being a CEO is probably the hardest jobs out there. It's a lonely job to a degree. It depends how you of course structure the people around you. I always say that, in my company, to my team, I'm the least known person; I know the least amount of information in the company. I always tell them, think of a company like a pyramid; I'm at the top, which means I'm the most clueless person in the company, and that basically to drive more information upstream and also make more decisions downstream by themselves. But being a founder is a difficult role because you have to balance a lot of needs. You have different stakeholders from shareholders to partners to employees.

And in the same breath, you operate under a lot of stress. So, it's definitely not for everyone, and it's very hard. And I think one of the key traits for a successful founder is resilience and curiosity. Resilience because most things will not happen if you imagine them to happen. They're more likely to be more difficult, especially if you're working on something worthy enough that has huge opportunity. It just makes it more difficult. So as a founder, you need to know that you're getting into a very stressful environment. The company becomes your identity, and resilience is the key for success. It's not knowledge, necessarily.

In fact, if you look at the most successful companies, the reason they even exist is because the founders or the founder’s thought it's going to be easier than it wouldn't. If they would've known how difficult it would be, they probably wouldn't have done it. So that's on the founder's side. But risk taking, there's a few elements there. Number one, my point of view about founders or at least good founders is that they are the most risk averse people I've met. I know it sounds counterintuitive, but in my view, being an employee is much riskier than being a founder, because it's very hard to fire a founder. Not impossible, but very difficult. Very easy to fire an employee.

At least as a founder you control your own destiny, whereas an employee you don't. If you look at it from a salary perspective, career perspective, being a founder is much less risky from my point of view. However, being a founder does require you to look at the risks differently, and that's what great founders do. As you go through your career as a founder or as you build your company as a founder, I always say that the job of a founder is to continuously identify risks and mitigate those risks over time. As the company grows from being a seed stage to a serious C stage, the majority of the risks should be mitigated or completely removed.

So again, it's not about taking risks. It's about the ability to identify to identify them, find a perspective on how to mitigate them, and then execute properly on their mitigation. That's the type of risks I think founders are involved in continuously to manage. And lastly about risk, and that also connects to my background from Israel, it's largely connected to the culture that the person is growing up into. I'll give you an example. When I first came to London and started to build my own company, one of the things I realized very quickly is that the people in the UK, also largely European, are highly risk averse. They are afraid of failing, and being afraid of failure is a huge detriment to one's growth. Growth mentality, growth mindset requires you to be comfortable with failure, because by failing, that's how you learn.

And I think a large part of that is to do with the culture, especially the British culture, where... In Israel, if someone fails, we have this thing called [inaudible], which basically, what it means is someone would look at you, tell you, "Wow, that sounds horrible. I'm sorry you failed this way," and they give you a slap on the back of your neck, which is... it's not a hurtful slap, but it's a powerful one because your entire body moves forward. And this is kind of for us to tell the person like just, "Move on. Learn from the failure and move on." That's the mentality in Israel, it's okay to fail, it's part of your growth; it's an inevitable part of your growth, where here in the UK, when I see companions failing, when you see founders or individuals failing, you see that their family, their friends are pointing the finger and said, "Yeah, this guy, this lady failed."

And that's not good, because that means that people will take less risks and will grow less, and if people will grow less, companions will grow less, and if companies will grow less, the economy will grow less. So it creates a vicious cycle of innovation and growth in the market, and in individual growth. And that's I think mostly cultural.

Lex Sokolin:

I would absolutely echo your point about the job of the founder is to mitigate risk, and that contradiction of you have to set the flag to do the hard thing, and then as you scale up the mountain, you're not focused on making it harder; you're focused it on making it more safe as you're going up the mountain. And then, once you get more and more people along with you, you got to make it super safe, because now you're responsible in a big way for customers and employees and so on. Okay. So that gets us to Curve, and what it means to start something, which I really appreciate.

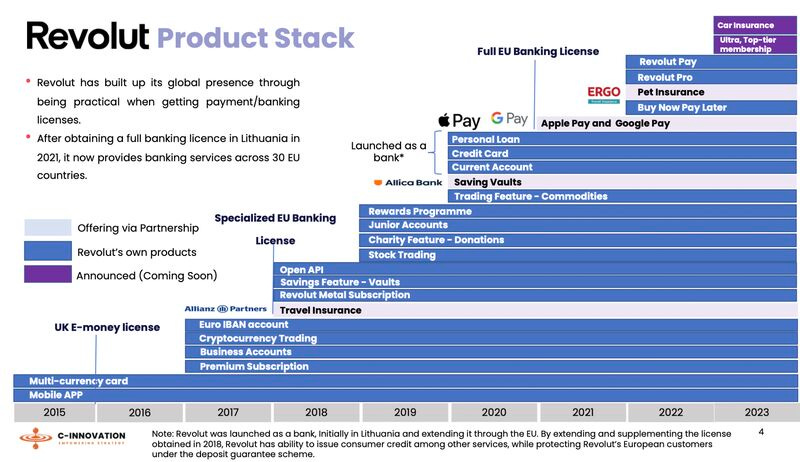

It's 2015, you've got some neo-bank startups, you've got payment startups like Venmo, you've got the Monzos and the Revoluts and the TransferWise. In the US, you have the robo-advisers. Lots of people are building fintech stuff that sits on top of traditional finance architecture. Let's talk about what was the initial idea behind Curve, and what was your first series of moves to make it happen?

Shachar Bialick:

Yes, indeed. So you look at 2015, you start seeing the unbundling of the banks and a lot of new payment companies, now referred to as fintech companies, evolving. And when I looked around me and saw the market begin its unbundling journey, immediately I moved into, okay, that's great, but we already know that markets are moving in permanent movement between unbundling and re-bundling. It happened in many other markets like travel with booking and shopping with Amazon and music with Spotify. Therefore, immediately I deducted that the market will re-bundle eventually, will converge eventually, and the only question I had in mind were, how much the time will the conversions take? Number two, what type of product or race car would be able to win that convergence race?

So look at 2015, as I start to form our market policies, I concluded that it will take about seven to 10 years for the market to converge. We were bang on the money. A bit on the later side of nine to 10 years. And we thought about, what will be that convergence point where customers will have the single point of access to everything money. Very quickly, I concluded that the wallet interface would be that interface. Of course, it was very hard to imagine a neuro link interface already to your brain. It might be the interface eventually, but right now it's the smartphone interface that allows you to have this access, and within the smartphones, payments is the best wedge into the convergence. And therefore, the wallet is the right solution.

Then the problem that emerged was not every wallet would be able to deliver that solution, because to converge the market, one needs to converge the fermentation in the market. A good example of fermentation back then, a very simple example of that, was that as a customer, you have three to six different cards... let's focus on cards for example. And you want to use a debit card or a credit card from this bank or that issuer, you have to go to your wallet and pick it up the right one, and also know which offering each one gives you, so you have to have savvy with the offering of each one to minimize your costs, to maximize your rewards or whatever benefits the card gives you.

But why would the customer have so many cards? Why would it not be one single interface that makes the entire ecosystem, an entire pack of cards into a tangible solution where the customer, their identity, is able to connect to all of them in one place? Back then, also if you look at the history, you had this company called Coin in the US. What they've done, they've mimicked your underlying card [inaudible] data into a physical hardware card that [inaudible] them all. But the problem with that solution was, put aside it's hardware, which is harder to do, is it doesn't solve the fragmentation problem. It only solved the symptom of fragmentation which is the outcome that you have multiple cards.

The root cause to the fact they have multiple cards is fragmentation of identity, of relationship management and offering by the various different ecosystem players. Now with that insight, we looked at what technologies are available in the market, and the only technology that was sold that was available in the market was what referred to as the pass-through technology. It's the technology of wallet that the networks Visa and MasterCard created for the likes of Apple, Google and Samsung. And the problem with this technology is that the networks were very, very concerned about their OEMs like Apple taking ownership of their customer and controlling the customer destiny, because that would impact the networks' customers, which are the issuers.

So the networks created the pass through technology in a way that the OEMs, Apple, doesn't have any access to data, and what the technology does, it just mimics the customer using their plastic card at the point of sale, but now they use it in a digital form. So, when I pay with my Apple Pay in my Barclays card, it works exactly the same as if I would pay with my Barclays card directly. And that meant that the wallet, the pass-through wallet, doesn't solve fragmentation. All it does, it moves all my physical wallet with five cards in it to a digital form with five cards in it. It still doesn't allow me to do all the unique benefits that should happen from Convergence. So that technology, in our view, was not likely to win at convergence.

But most importantly, if I'm to use the same technology that Apple uses, there's no way I can win Apple in their own game. One reason is because I'm not Apple brand. Second reason is because Apple controls the divides, controls the OEMs. They would always have unfair advantage on the experience, so I have to have something which is better than Apple that Apple cannot do. And thirdly, the pass-through technology works requires the likes of Apple to partner with each and every bank and merchant acquirer separately. And you can see a good example of Samsung Pay, even though they have a big brand, they were still not able to get much coverage from issuers in the market. A good example in the UK, it would only have 50% market coverage of banks, and this is 10 years after they launched in the UK. They don't have support from Lloyds and Barclays and very large issuers in the UK.

The pass-through technology wallet is unlikely to be the wallet that will converge the market, unlikely to be the one that Curve can win that we imagined would happen 10 years down the line. So, we had to think of a new solution, and we saw quite a remarkable idea by Google back in 2011, 2012 called Google Wallet. Do you remember that Lex, the Google Wallet from 2011, 2012?

Lex Sokolin:

Yeah. I mean, it came, and it went. I remember it.

Shachar Bialick:

It came, and it went, right? It was a pretty smart solution. Basically, what they said, we will tokenize all your cards on the Google ecosystem, and we're only going to give you one token, one access to all those cards from... that one token was back in the day, a card. One physical card to rule them all. But the problem they had was that one of the large issuers in the US really didn't like that solution, because that would disintermediate them, right? And what happened is that the day prior to launch, they were supposed to launch it not in 2020, in 2012. The day prior to launch, Visa sent them a cease and desist and killed the product before it even went and came alive.

And that was the last we heard about the product and Google decided not to fight Visa and just left it as is. Eventually, it just went with the pass-through wallet. So, the solution Google put to the market actually did converge everything into one place, because that solution would give Google all the data and their phone would allow Google to personalize to the customer the right offering at the right time. So, the Google Wallet solution is the right solution, but the networks don't want to give it, and you have to give the networks access to be able to succeed in that solution.

So that's Curve emerged. I already had four companies, all had very nice exits, but nothing that really have made such a big impact, and both in terms of monitoring important shareholders but also on customers. And I decided, if I'm going to go and do another startup, my fifth one, this time I'm going to go full-in. I'm going to go and build something that is really, really hard to build, something that's inevitable to happen in the market. I may fail, I may succeed, but let's try. Who knows? And little did I know it's going to be very, very hard, but I knew it's going to be a complex coalition problem. A problem where I have to change rules and bring different entities together, obviously align with their interests, at least not initially until they realize more specifically what the product means and how it works.

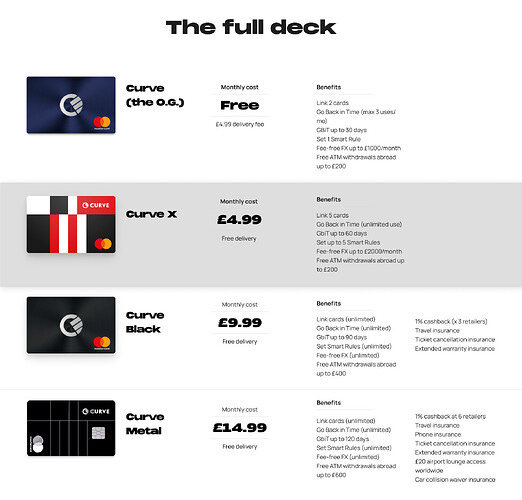

And that's how the journey started of Curve. That type of technology that we're talking about, that Curve is still referred to by the industry as back-to-back wallet or stage wallet. Different networks use different naming, but basically, the solution is such that allows customers to have all their cards in one card, and that card is basically intercepting the initial authorization to give customers more value. For example, Curve allows you to make all your cards zero FX, so anywhere you go and pay, as long as you paid with your Barclays through Curve Pay or Curve Card, Curve will eliminate the fees that Barclays would have otherwise charged you.

Something like Apple Pay, just to give a tangible example, if you use my Barclays card directly in the US, I would charge 3%. If you use my Barclays card through Apple Pay, I would be charged 2%, because it's akin to using my physical card on a digital form. However, if I use my Barclays through Curve Pay or the Curve Card, Curve would eliminate the 2% that Barclays would otherwise charge me, and it would also give me 1% cashback, but that's aside.

Lex Sokolin:

How do you start building something like this, because what you've described I think as an idea is pretty compelling, but it's pretty complicated to build. So where did you start? What kind of people did you need to hire to get going and what were the first couple of years like? Did you see the adoption you expected? How did you get new customers? What was the practical reality of it?

Shachar Bialick:

Curve initially, and still is, is very much an extremely innovative product within the payment space. So we always refer to ourselves as explorers. We don't know what will come. We are trailblazing. We're creating a trail ourselves. When Curve started first, I got talking with some previous shareholders, and VCs in the industry, and many of them thought it's going to be impossible because the networks will not allow you to do that, is going to be impossible because you have seven seconds to reply the network and there's no way you can do two transactions across the world and approve at the same time, or it's impossible because commercially it cannot work.

And those are the three risks or concerns I had to approach head-on. The only concern I could really approach head-on was the second one which was, it is impossible to do it in the time you have, technically, which to me is a technical problem. I'm good on technical problems. I knew how to solve it. It's akin to the traveling salesman problem that exists in the... You're familiar it as a customer when you're using navigators. So, the first thing I've done is create a proof of concept to show it's possible to solve the second problem. And with that, I started to go raise money for a seed stage.

You can imagine our seed stage supporters, shareholders, where I told them, "We may not get a license from MasterCard or Visa, and we may not find a commercial model, although we do believe it exists there. There's still a modeling going forward. So, after the seed stage raised and a proof of concept in play, I went to MasterCard and told MasterCard we want to issue MasterCard cards based on back to back funding or card fronting in another language we were using back at the time. And that meeting was [inaudible] because at the end in the meeting, I was just laughed out of the room, literally. They laughed at me and said, "There's no way we going to give you access to this one. Our rules don't permit it. Google tried and failed. We won't give it to you."

But what happened immediately after this meeting, as I was being hurried into the elevator, a remarkable [inaudible] MasterCard, [inaudible] leading all fintech in Europe, his name is Darren Deal, told me, "Listen, I can't promise you we'll be able to change the rules, but within my remit, I can give you a waiver. But the waiver is only in the UK, only for small, medium businesses, prepaid card. And go try the technology on this small market, prove the point, get data points, and I promise I'll put you in front of the leadership team at MasterCard, and then you will have your day to convince them to change the rules."

And indeed, in February 2016, we launched for a small subset of the UK population, SMBs, with the Curve Card. It was highly successful. We managed much less growth, but we were able to get I think within three months to about 50,000 [inaudible] customers. Very, very high growth. And a year afterwards, where we grew to quite a significant amount of [inaudible] customers and a lot of data points, Darren was true to his word, he put me in front of the leadership team at MasterCard and New York, and I remember the meeting was there with... even Michael Miebach was there, who back then was leading consumer products and at MasterCard, now is the CEO.

And I'm sharing with them our view of the market, how it will converge, how often banking will come into play, how PSD2 plays into that, where MasterCard's role should be in all that innovation, and how Curve can help MasterCard drive innovation forward and partner with Curve. And this meeting was very successful, because at the end of it, MasterCard changed their rules and allowed us to start operating across all the market, consumers and commercial customers in the UK and Europe. And subsequently, a couple of years afterwards, they also changed the rules globally to allow us to operate in all markets, including the US.

In between, because Curve was issued on a MasterCard rail and still is, and it's fronting Visa transactions, Curve and Visa had a lot of back and forth between us for almost five years, until 2020. In 2020, the discussion with Visa started to accelerate in a negative way, to the point that we were concerned of continuing to operate the business model in the market with Visa. But through a lot of work and relationship work with executives of Visa, all the way to the CEO, we were able to convince Visa to change the rules also in UK and Europe. And with that, we also removed the risk of Visa network from killing our company or the business model of the company, and not only that, we also became very good partners with Visa. And now Curve is a principal member of Visa, and next year you're going to start seeing us with Visa cards in the market.

So that's an example of how reducing risk over time, and convincing the networks to change the rules, where initially they didn't want to change the rules. They didn't think it was right for their issuers, but it took a lot of education and relationship work for them to see the values for themselves and the issuers that Curve works with, and Visa and MasterCard works with. So that's kind of the beginning of Curve, I would say, and the [inaudible] coalition. What transpired from that is that now, especially in the past year, everyone in the market from issuers to OEMs to the PayPals of the world, MasterCard of the world, Visa of the world, all realized that the phone factor is changing. It's no longer the card, it's the wallet. The wallet is a very low-cost of acquisition to bring customers in. They have a lot of data on the customer, and [inaudible] services for the banks or the networks or the OEMs.

At the same breath, also we start seeing the market opening up with regard to wallets. So we can talk about what Curve did with Apple and how Curve opened with the European Commission the Apple NFC and how it's followed.

Lex Sokolin:

This is exactly my next question, is how your relationship with the hardware providers of all is...

Shachar Bialick:

So one of the issues we had is Curve was never really a card. It was always a wallet, but on Android devices, we could be a wallet, where they deployed to the NFC, and Curve is the de facto default wallet. But on IOS devices we couldn't. And that has created problems for us, we cannot go to market and position Curve to one set of customer segments, Android users, as a wallet, but for another set of customer audience, IOS users, as a card, because we had to put the Curve Card inside the Apple NFC to access the NFC, and pay Apple quite a significant amount of money for every transaction. So, we decided a long time ago that we have to lead with the card until we opening up the Apple NFC.

But in June 2020, we became big enough as a company, and we started to see the impact of people referring to Curve as a card, not a wallet. In fact, we have a T-shirt in the company, a T-shirt, on the front of it called... there's two words, challenger bank, and bank is being scratched out, because we're always telling people, "We're not Revolut. We're not Monzo. We're not Starling. We have a great product, load into Curve and use it." That product... the way that people think about Curve because we led with the card was really the detriment to our growth. So in June 2020, we're starting the company and project called Project Elah. It's based on the Elah Valley in Israel, where David fought Goliath and won.

And Project Elah was basically Curve reached out to the regulator in Europe and told the European Commission we believe Apple is being anti-competitive but not opening up their NFC, and their excuse of security and privacy is merely an excuse, because obviously there's no problem with security and privacy, because Android devices opened the NFC, and there's no issues there. No fraud or email or security issues. It can obviously work. And three and a half years later, in January 2024, just about nine months ago, 10 months ago, Apple conceded to open the NFC in the European market for free. What we envisioned would happen is that once Apple loses in one market the security and privacy excuse, other markets will follow through to open their NFC; we just thought it's going to take much longer. We were surprised to see already in February the DOJ, which is a very busy regulator, already start suing Apple to open the NFC in Europe.

And in April, May this year, the UK PSR have already started to reach out to market participants for guidance on our thoughts about Apple and its restrictions on NFC access. And what transpired is that Apple did the first move in August about two months ago, and in that move, Apple basically decided to be on the front foot and open the NFC across all key markets, from the UK to Australia to Latin America and the US. The main question there however is when they opened the NFC in those markets, unlike in Europe where they opened the access for HCE, which is host card evolution in the cloud, in the UK and US, they opened the secure element hardware itself.

And they intend to charge for that commercial fee, which we don't quite know what they are. We assume it's not a transaction-based commercial fee, more like around tokenization. But either way, what we found strange is that in Europe, they don't charge anything, and yet our neighboring country, UK, they do charge. And we believe that's very much because the regulator was very slow to act, and I think that's going to be a very big question whether Apple will be able to charge any fees in the UK, whereas in Europe they don't charge any fees. I don't think the UK government or regulators will allow it to happen, but time will tell.

Lex Sokolin:

That's a really difficult thing to accomplish. We talked about mitigating risk before. Were there things that you were doing to mitigate the risk to the company from having exposure to these kinds of tectonic plates of industry? Were there parts of the business that you were setting up to take advantage of the opportunity? Like how did you shape the company the company and the organization to try and be responsive to the landscape?

Shachar Bialick:

First and foremost, the way we saw the risk of Apple not opening up the NFC at all, and the way to mitigate it was always through the Curve card. The second way to mitigate this risk was being on the front foot and driving those changes in regulation and industry. We drove those rule change with MasterCard and Visa. We drove change in open banking when we were part of the open banking initiative and how the organisation should work, and some things they've taken, some things they haven't, unfortunately. And we've seen the issues of not taking some of the advice from the industry into the adoption of open banking. We can talk about it a bit later.

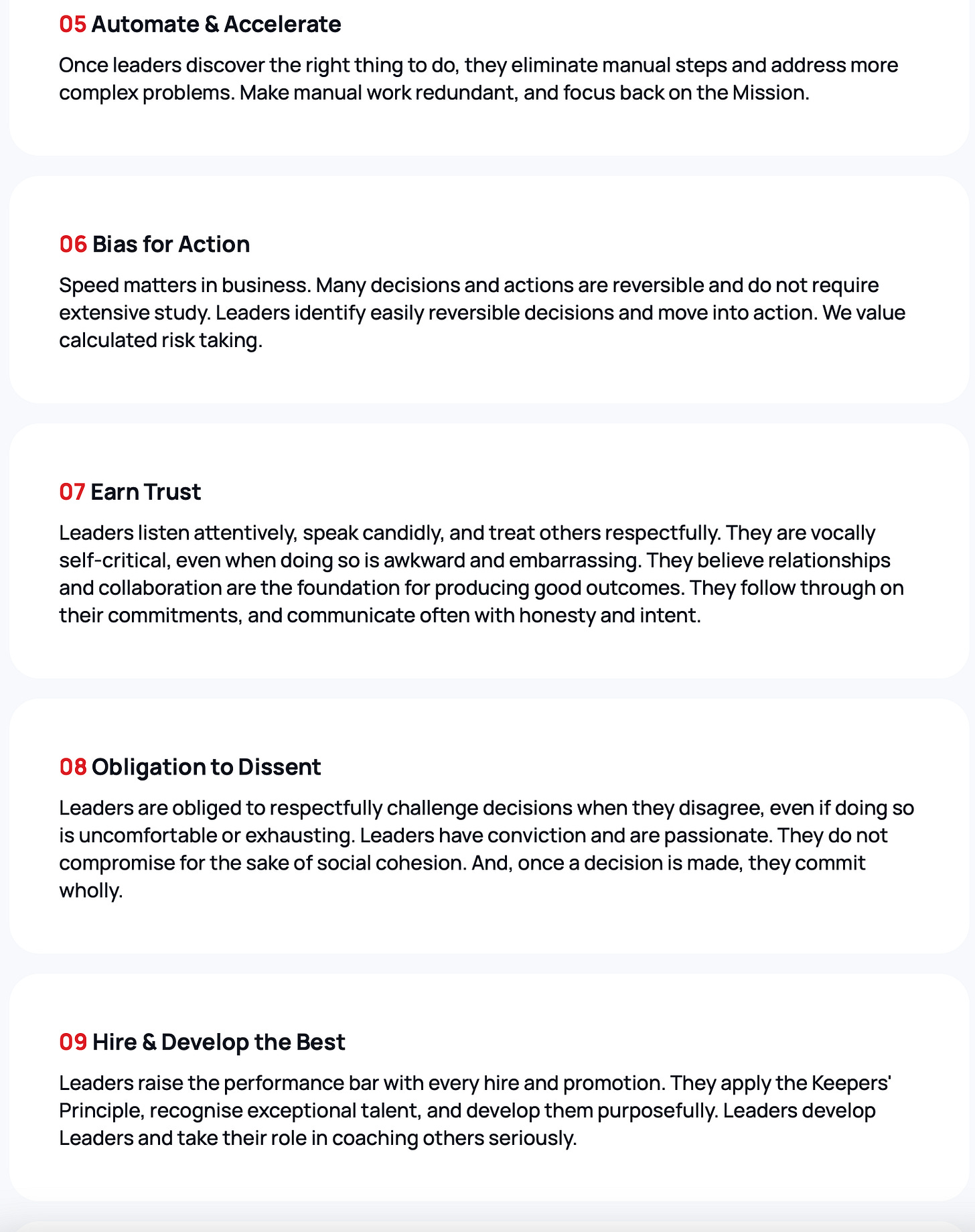

And it starts with Apple, where we actively worked to open NFC and the change we made globally with Apple NFC, leveraging of course the regulator's power in the market. In terms of company and how to structure organization and leadership to drive that type of innovation and trailblazing and confidence and mitigating risk to identify true industry changes or product changes, it really has to do with the culture I think of the company and the people you're able to bring in.

First of all, we will always err on talents that are smarter, capable, resilient, curious, than are more experienced. We prefer people who are less experienced but have this hunger and curiosity, adaptability and resilience, over highly experienced people that have been there, done that. Also, because highly experienced people are very biased. If I wanted to tell someone who's very experienced, "Hey, let's change network rules," they will immediately tell you, "It's impossible. We tried and failed. Why would you succeed?" But if you bring someone who's hungry and resilient and smart and curious, and tell him, "Let's change the network rules," they will tell you, "Let's do it."

I'll give you an analogy that my COO always gives me, and I really like it, is when you're telling a 25 year old, "Go shave the lion," they're happy and excited to go shave the lion, because they just don't know they might lose a leg or an arm. But when you tell someone who's 50 years old, go shave the lion, they know they might lose a leg or an arm, so they're much more careful on how they approach it. Sometimes this carefulness is relevant, you need to have experience, but sometimes actually it's distracting you from the ability to make this change.

That's how we bring those type of talents. And then during the lifetime of the company, we have 10 leadership principles we operate against, and one of them is to think big and innovate. And it starts, this principle, with everything is possible. As our talents come into the company, there's an induction of one hour I'm taking with them, explaining the principles and how we operate, how we recognize people. And I take them through this principle, and I tell them, "The reason this principle starts with everything is possible, is because you grew up in an environment that your teachers, your parents, your friends, always told you, no. No, it's not possible. No, you can't do this. No, you can't do that." Which we always felt is strange because those are all manmade rules and therefore man can change it.

And if you have this mindset, that it's not possible, you would fail by definition. But if you have this mindset that it's possible, you may still fail, but you have a chance to succeed. And therefore, you always have to start every day, every action you're doing, that it's possible. And the only question is why you think it isn't, to try to solve the problem. And you see it in many aspects of Curve where there's so many things they always told us is impossible, experts in the industry, and we always found a way to find a solution and go around the problem to solve what we solved for. There's a list of about 20 of those I can think of, that again and again it's succeeding and achieving. But it's all in the end, culture and having the right people around you.

Lex Sokolin:

I think it's just so exciting to have this opportunity now from Apple and actually be able to displace or augment the default. I think Apple's one of the biggest gatekeepers of all technology, whether it's payments, but it's also artificial intelligence. Huge gatekeeping of that, going to happen. Cryptocurrency, wallets, all of these things.

Shachar Bialick:

Well, it is a great opportunity. There's no question there. But let's say I'm PayPal for a second, and I have a large customer base and a large brand, and now Apple Pay has opened the NFC, and I, PayPal, have to move to a brick-and-mortar space to expand my revenue, expand my market. Just to operate online is very restrictive for the growth of PayPal. But if I'm going and creating a wallet, and all that wallet does is what Apple Pay does, because using a pass-through technology, the available technology in the market, then why would I as a customer leave Apple and move to PayPal Pay? There's no real reason for me to do that, because Apple Pay has pretty meticulous experience, pretty remarkable experience to begin with, and if PayPal has pass through wallet technology, there's nothing that they can offer me that Apple don't offer me already.

To be able to take away market share from Apple Pay, and I'm using Apple Pay just as an example of other... like Samsung Pay, Google Pay, but just because they're also very, very... the best experience I think in payments today. But to take away customers from Apple Pay and move them to your X Pay, you have to offer a tangible benefit to the customer that Apple cannot offer. Not don't offer, cannot offer, technically. And this is where you see, in a tangible form, the value of the technology Curve built and fought for in the past almost 10 years, because Curve Pay, unlike Apple Pay, make all your cards zero FX. Curve Pay, unlike Apple Pay, allows you to earn rewards for your underlying cards, plus rewards from Curve. Double dip rewards.

Curve Pay, unlike Apple Pay, has a companion wallet in the card, that allows you to spend money where contact is not available. Online, ATM, point of sale, and so forth. So the way we think about it is that the only middleware today that has a chance to win against Apple, or the only middleware technology that has a chance to win against Apple, is the Curve middleware technology, because it can offer easily verifiable, tangible benefits to customers, that the competition cannot offer.

Lex Sokolin:

Absolutely, you can't just create the same thing and hope for a different result. Let's talk about the evolution of the fintech space, in particular. Since that 2015, 2016 moment, we've had a lot of progress in open banking in the US, in embedded finance, whether it's through middleware platforms, although that's of course been challenged, or whether it's been through mandated APIs. The CFPB just recently passed rule 1033 which is pushing an open banking-like standard in the US as well. What do you think about the landscape of infrastructure in our industry? Where is that going and how do you see that overlapping with your business?

Shachar Bialick:

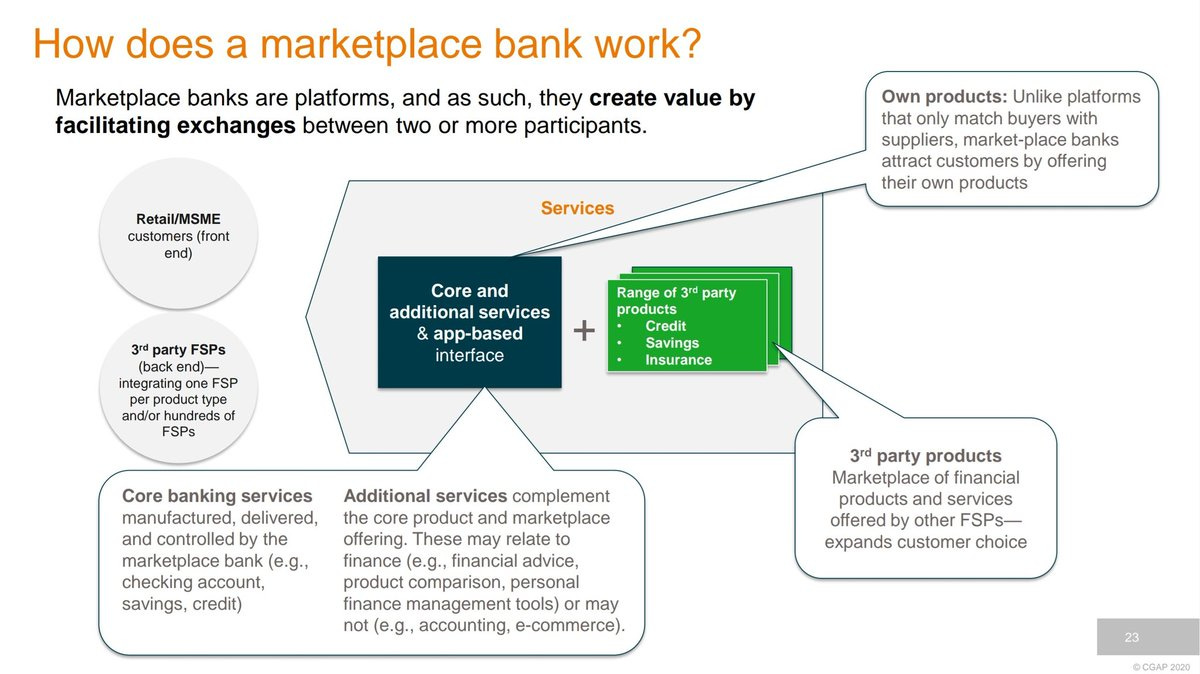

That's a good question. If you look at 2015, let's just talk about some startups and how they evolved as an example of what's happening in the market. You saw the neo-banks, the Monzo, the Revolut, the Starling of the world. Those companies, if you read and remember the original vision, was we're going to create a marketplace bank. Monzo was a big proponent of that. We always said that a bank cannot be a marketplace. It's conflicting interests. For example, a bank must lend. So, what would happen as a lending marketplace? What, the bank would take the best customers and all the less affordable, low credit score, subprime customers would go to other banks? It will never work for them.

Moreover, being a bank requires you to change your behavior. Stop using other banks and use their banks instead, where your salary will come in, which means you're directly competing with the banks. So that means you cannot be an ecosystem play. And it's also quite a bar to get customers to leave Barclays and trust a fintech. And indeed, 10 years later, you see that Monzo is a great bank, competing with Barclays, but it's not a marketplace. They in fact lost the marketplace vision all together. They gave up on that. Similarly, Starling gave up on the marketplace vision all together. Revolut, who's done remarkable execution in the market, and if they're able to introduce, on top of their FX offering, trading offering and other offerings to customers, have also became a bank. They're not creating a real marketplace of financial products. They're creating their own products to try and take them away from other companies.

So the marketplace vision is no longer in the world, unless you have a wallet that is really an ecosystem play. And that I feel is very much a shame because I've always felt that the true innovation of fintech is not to create a better bank... not to say that there isn't an opportunity there. There obviously is. We can see from Revolut, Starling and Monzo just in our small UK market. But this is not the real innovation. The real innovation is to become your personal CFO, to be able to see your data and allow the customer to understand and discover new financial products and services that fit the bill for that connecting between the relevant financial provider to the relevant customer in realtime. And that requires the solution to be an interface where the customer trusts with their data and highly engaged with to allow the customer to discover those products and services and the service provider, the wallet provider, to connect the dots between the financial entity to the customer.

Now, at the same time of seeing the marketplace vision going further and further way from the neo-banks, you also saw that those neo-banks also have a challenge of cross and upselling products and services. Let's take Revolut as an example. Revolut did a remarkable job on the FX side and were able to take a lot of retail and backpacker consumers to reduce their costs as they travel on FX. And from there, they start to build more services. But recently you saw Revolut extracting the trading platform from their main app to a single, separate app. You must ask yourself, why did they do that? And the answer is because when you are not the single place from which people access their money, but rather solving only for one job to be done, i.e. I'm using Revolut just for when I travel, not for my everything finance, that creates lack of engagement and therefore impacts your ability to cross and upsell financial products and services.

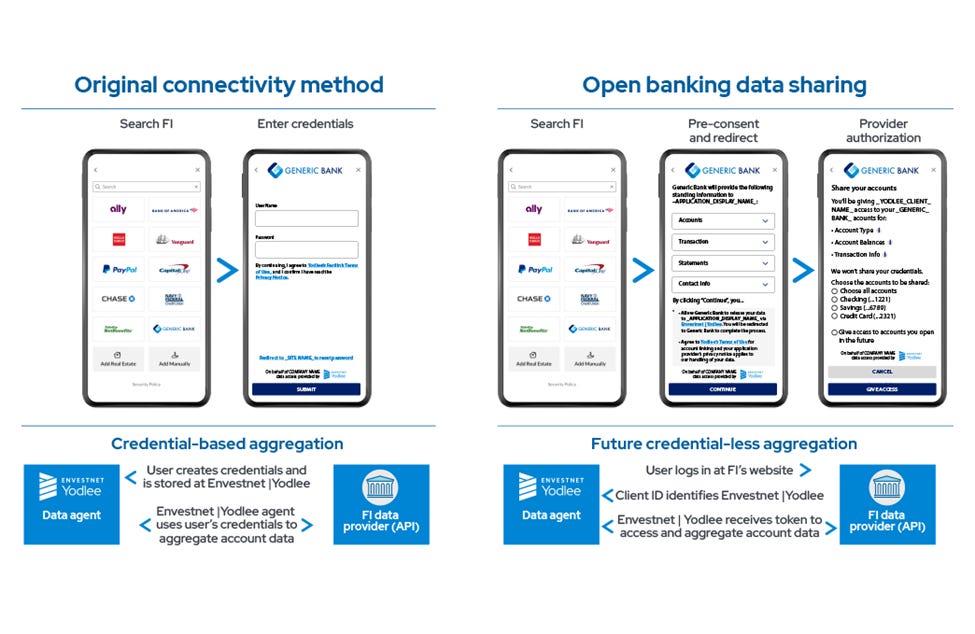

And in comparison, to products like Curve for example, where it doesn't matter which card you want to use or which bank you want to use or which financial service you want to use, you can keep spending from the same wallet, the same interface. Continuously it's the one you're opening up and spending, which gives the wallet operator much more data, and therefore much more data to cross and upsell the right service to the customer, which [inaudible] the customer, whether it's your service or a third-party service. This is from the customer, consumer perspective. Other things happen in the market is... [inaudible] was the beginning of that [inaudible] really brought it into the fold with open banking.

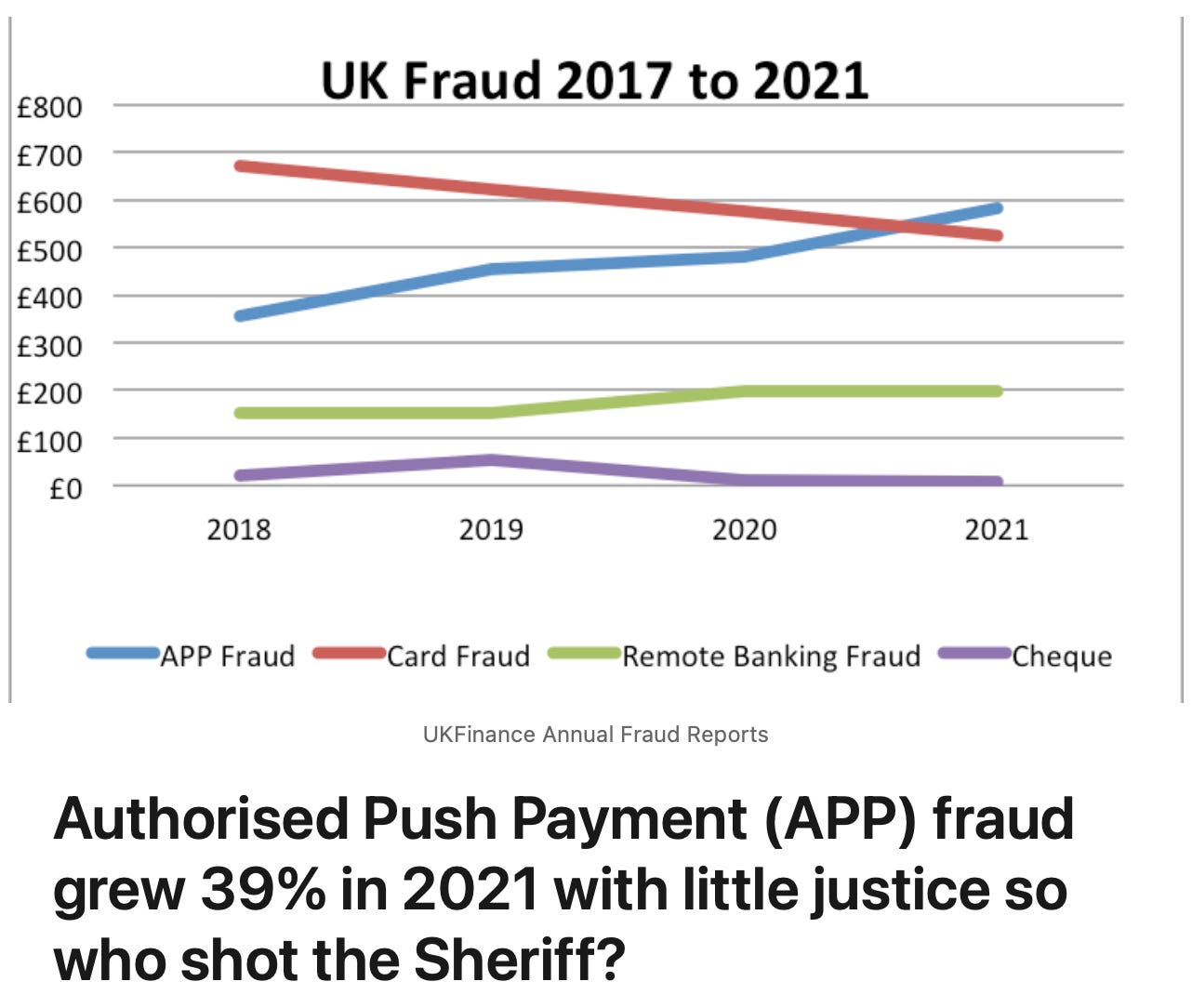

And there, what we're seeing is that the regulators have tried to create a competing network that is much lower cost to the Visa, MasterCard networks, which is a great call, a great objective. And they were able to bring the banks together, create the APIs. But what they were lacking, and that was the main feedback we gave, and not only us, the main industry participants to the regulators, that they were lacking standardization of API, and and they were lacking standardization of chargebacks, fraud rules. If you think of MasterCard networks, everyone thinks of them as a payment network, which I always think is wrong, or at least insufficient.

Visa and MasterCard networks are networks that provide trust, number one, standards, number two, and payment remittance, number three. The payment remittance technology is simple. It's basic. In fact, today Blockchain do a much better job than what Visa and MasterCard does. The real power of Visa and MasterCard is their standardization of network rules, which are the chargeback and API that drive the trust and success of every transaction that you have. And if the transaction was a fraudulent transaction, you know you are protected by the chargeback rules, and the different participants know how the rules work and where the liability sits.

But when it comes to open banking, they forgot to create the standardization of APIs, and forgot to create to address at all the fraud and chargeback rules. The outcome is that, if a company like Curve wants to connect to banks, we have to have the right integration within every one of them, and every integration isdifferent. Even companies like Tink and TrueLayer who are aggregators of open banking also struggle with that. The second problem, let's say you manage to bring all the banks together and somehow create some sort of standardization, which is really hard, what's happening with chargeback rules and fraud rules? There is a complete lack of rules there. We don't know what would happen.

And the app fraud rules recently that we introduced, we're trying to solve some of that. But the way it's solved is also poor because it puts the onus on the gatekeeper bank, which is strange, because it creates a moral hazard problem with the customer. I now don't need to worry about fraud anymore, because whatever negligence I do, my bank will pay for that. But more importantly, it puts the onus on the wrong side of the equation, because if a fraudster got into the banking system to defraud you and move money from the customer account fraudulently into their account, surely the bank that opened the bank account to the fraudster should take the majority or all of the fraud, because that will put the moral hazard on the right place. Hey, banks. When you on board customers and give them access to the banking system, make sure they're not fraudsters, because if you don't make sure they're fraudsters, if you don't do KYC or KYD properly, you will get entire fraud that happened in this account.

So, there was a lot of problems. And a good example of the fraud app issue we have in the UK, the regulator does understand fraud properly and how incentives should operate properly and moral hazard. And I just think that's one of the key feedback the industry gave back to the app fraud that we introduced, but also the key feedback we've always given to open banking. And if we fast forward from 2017, 2018 when we gave the feedback for the first time to the regulators, to today, this gap in the market, in open banking, of lack of standardization and lack of chargeback rules, creates what? An opportunity. To whom? To Visa. And indeed, Visa, in September this year, has announced the Visa account solution.

And what are they highlighting in the Visa Account Solution? They're highlighting that they're leveraging their Tink asset that they've acquired a few years back, and they're adding to the Tink asset two new things, standardization of API and standardization of chargeback rules. So now, I'm a fintech participant in the payment space. I have a choice to go with TrueLayer or to go directly banks, or I have a choice to go with Visa. Which one will I choose? There's no question anymore. I will go with Visa, because Visa give me one API and everything else is standardized, and when it comes to fraud and chargebacks, Visa give me the solution to the Visa network rules. A great move by Visa.

The problem here of course is that it directly goes against the objective of the regulator, which is creating an independent, lower cost network. That was the biggest problem we saw, and now we're living through that of open banking.

Lex Sokolin:

It feels like it'll take years and years to churn through all the possible paths before we get to something better.

Shachar Bialick:

It will take time, yeah. But the good news is that we are now seeing... in the US, you mentioned CFPB rule 1033, and it's kind of funny because you're seeing exactly the same reaction by the banks in the US, the same reaction you got back in 2017, 2018 here in Europe. And you've seen also the same challenges in the law they're introducing there, in the rule they're introducing there, that lacks the standardization of APIs and lacks standardization of chargeback and fraud rules, which means that the outcome will be a very similar outcome to what we saw in Europe, which is very lacking.

Lex Sokolin:

Absolutely. Well, thank you so much for diving into all of these topics and opening them up for us. If our listeners want to learn more about you or about Curve, where should they go?

Shachar Bialick:

To learn more about Curve, they should go to our website, curve.com. To learn more about myself, they connect me or look at me at LinkedIn profile, or just follow the fintech influencers, like you Lex.

Lex Sokolin:

Very kind of you.

Shachar Bialick:

We learn a lot about the industry from you guys.

Lex Sokolin:

Thank you so much for joining us today.

Shachar Bialick:

Of course, Lex. My pleasure. Thank you so much.

Postscript

Sponsor the Fintech Blueprint and reach over 200,000 professionals.

👉 Reach out here.Read our Disclaimer here — this newsletter does not provide investment advice

For access to all our premium content and archives, consider supporting us with a subscription.

Share this post